Marcos Asks the People to Listen to Each Other

In Anencuilco, Morelos, the Zapatista Subcomandante, Speaking on the Political System, Draws a Line in the Sand

By Bertha Rodríguez Santos

The Other Journalism with the Other Campaign in Morelos

April 17, 2006

ANENCUILCO, MORELOS: A profound feeling of connection between the local people and the Zapatista delegate of the commission promoting the Sixth Declaration of the Lacandon Jungle, Subcomandante Marcos, was expressed in these lands in which the noble and valiant spirit that guided the revolutionary struggle of General Emiliano Zapata Salazar can still be perceived among the peasant farmers and the people from below.

The gestures of affection toward the Zapatista delegate occur after and despite the history that gave birth to this movement: the violence of the rich toward the peasantry, the repression, the blood, the suffering, the lives of those who have committed suicide because they no longer have any way to survive the economic crises, the lack of work and hunger, the brazen theft of their land; the stories cut short of those souls devoured by a system that has placed humanity on the edge of the abyss.

The people make clear that a visit from Marcos to any part of the country is a special event, especially the forgotten people of the countryside. Marcos’ words, far from the politicians’ elaborate discourses, come out calmly, often with a large dose of humor, and break with the worn-out and empty language heard in the mass media. Not reading from any script, Marcos shares these words as if talking among friends. At other times, however, they are strong words charged with rebellion.

In this way, he is able to connect with the people. As Professor Alberto Hijar told the Other Journalism, Marcos — unlike many activists and politicians — uses “the chueco (literally, ‘crooked’) language of the common people.” Through his voice, the people understand better what the Other Campaign is all about.

Delegate Zero’s tour consists of listening, thinking and synthesizing the experiences of anguish, pain, death and suffering, as well as the dreams and aspirations of those who have nothing and with these experiences put together what it is we want to make of this world and this country before it slips completely from between out fingers.

The Other Campaign is a challenge to imagination, tolerance and intelligence; it is a trial by fire that will test the authenticity that exists between discourse and practice, between words and deeds, between the ego and essence of the human being and its most noble aspirations: Liberty, Justice and Democracy.

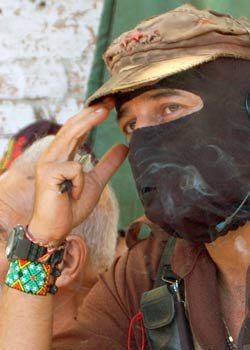

Marcos wearing a Huichol with peyote buttons. Photo: D.R. 2006 Nives Gobo |

Other say that Marcos is no longer Marcos, but the incarnation of something we all wish we were: Zorro, Robin Hood, Chucho el Roto, a poet in love, a lover of life and enemy of boredom and solemnity. Whatever he is, Marcos himself at times takes on the role of an indigenous person, a woman, et cetera, when he speaks of “we the indigenous” or “we the women.”

Sometimes, community representatives are the ones who best explain what is hurting Mexico from below and the way in which they would like to live; they are the ones who show Marcos this country’s true wealth. They give him poems, they include him in their chinelo dances (an ancient custom of mocking the whites by dressing up as European kings), they hang necklaces around his neck made of mayflowers or Guiechachi, give him cuexcomates, or old-fashioned clay jars used for storing corn, and in the Huichol towns they even presented him with a gift of two colorful bracelets, one with an image of the sacred peyote plant which he still wears as he takes notes on the testimonies of the people in struggle in each state.

In Tetelcingo, Morelos, the Catholics sang to him: “In this corner of América, the future is being born, a man with young blood goes through the valleys saying that on this fertile land, a new man is being born.”

In Morelia, Michoacán, the young people chanted as they marched: “Mar-cos es- un in-sur-gente, lo-quiere- toda- la gente, yo- tam-bién soy- za-pa-tista, mar-xis-ta-leni-nista” (“Marcos is an insurgent, all the people love him, I too am a Zapatista, a Marxist, a Leninist.”)

The men of the fields, sometimes choked up with emotion, show their commitment: “If I am the only one left it still won’t matter, they will have to pass over me, but they will not pass on to my land.” They assure that they will fight to the end to protect their land, their natural resources and their rights.

At other times, as in the case of the Willow Gorge, in the middle of a Cuernavaca residential neighborhood, the gift is for everyone. It is an unforgettable lesson. Flora Guerrero, Carlos Pérez, Alberto Mora, Azalea Calleja, Ruth Jimenez and Astrid Arias chained themselves to an oak, a guava, a laurel and other shade-giving trees, to prevent construction equipment that had arrived to to begin work on a bridge from uprooting them.

On April 10, around 9 in the morning, the neighbors and others organized by the environmental group Guardians of the Trees, camped out since April 5 in the entrance to the gorge, witnessed the arrival of four state police vehicles, mounted police, as well as 20 elite “grenadier” police.

With the police arrived two ambulances, predicting that the demonstrators’ removal would be a violent one. Nevertheless, as soon as the Other Campaign caravan traveled to the site, the police left, “running like hens.”

“They saved our lives. They saved us from the repression,” the environmentalists would later say.

Through the gorge runs the Salto de San Antón River, extremely polluted by the wastewater from the city once considered a land of “eternal spring.” There are many ahuehuete cyprus trees and amate fig trees there, as well as a great diversity of flora and fauna, including iguanas and macaws.

The presence of veteran guerrilla Félix Serdán, who fought with Rubén Jaramillo for the rights of the Zacatepec sugar plantation workers, lifted the demonstrators’ spirits, as did the machetes of the Atenco peasant farmers.

From community to community, Delegate Zero offers his words after listening to the participants, sometimes in short presentations and sometimes long ones. At all of these events he touches on the great themes of the anti-capitalist Other Campaign, often incorporating the histories of local struggles. The details change — he never gives the same speech twice — but the big issues such as the problem of the parties and the political system appear in many forms, over and over. For example, sometimes in rural or indigenous communities he will tell the story of how the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN in its Spanish initials) was founded and grew before the 1994 uprising.

“Lend Us Yours Ears to Listen to Others”

In Anenecuilco, the Morelos town where Zapata lies buried, Delegate Zero drew a line in the sand between the traditional form of doing politics — which in these times is characterized by wasting millions of pesos on electoral propaganda in the hopes of winning the presidency — and the Other Campaign.

Referring to the electoral season our country is currently in, he compared the political parties with employees of the old rich hacienda owners: “Up there, they have something we call foremen, to make a reference to the haciendas in the time of Porfirio Diaz, which Emiliano Zapata’s peasant movement destroyed. For us, these are today’s political parties.”

He speaks of the modern version of the old company stores, owned by the rich farmers and where instead of money, the peons used tokens to acquire the products necessary to survive the slavery of the farms. “Commodities are the basis of this system that we are confronting,” says Marcos, and adds: “This capitalist system converts everything into commodities and in these times, during this year and these months, we are now seeing politics’ conversion into a commodity. In that sense, just like before, they offer some clothes, some shoes, a bit of shampoo. And now they offer candidates and political parties.

“Lately, the policy proposals, the organizations that are fighting over the government, trying to govern, don’t matter. If there is a lesson to be learned, which is what we have to do with the politicians’ proposals as part of the Other Campaign, it is that there is no difference between them.”

Speaking to the cooperativists and the practitioners of liberation theology, among other adherents, Marcos explained: “That is to say, the politicians are not really proposing a transformation of the conditions that we are suffering. And so, as politics is no longer about moving forward, they offer us some food or products to buy our votes, they offer us a candidate, and now, not even a real political party. And an advertising campaign is built around that candidate.”

“We,” he continued, “we as workers, whether from the countryside or the city, as teachers, as students, even as grassroots Christian communities, are the consumers who have been given a credit card called a voter ID and which can only be used every three or six years. That credit card is then ceded to the winning candidate so that he can use it and profit for three years, for six years.”

In the middle of an advertising war between the presidential candidates, he said: “During this period we act even more as consumers. They try to convince all of us that the product we will be consuming is the good one, but the truth is that a landless peasant farmer, a street vendor or someone selling juice in the market is not the same as a big media owner, a landowner, the owner of Coca-Cola or its managers.”

“So, the same candidate, the same product tries to convince many different people. If we analyze this well, we will see that the street vendor or the landless peasant does not want the same thing as the big landowner or the owner of a shopping mall.”

Marcos explains: “We find that this product that is being sold in the elections changes. When it speaks with businessmen it tells them, ‘I am the good one’; when it speaks with the peasant farmers, ‘I am the good one’; as it speaks to the consumer, it says, ‘I am the good one.’”

Delegate Zero speaks about something that everyone wants to hear, and goes to the heart of the matter. “There is this trap, the politician that says, I am going to govern, I am going to lead this country for the benefit of all, ‘for the good of all.’ ‘So that things get done,’ as (Institutional Revolutionary Party, or PRI, candidate Roberto) Madrazo says. ‘For the good of all,’ (Party of the Democratic Revolution, or PRD candidate Andrés Manuel) López Obrador says. And as for (Felipe) Calderón, the National Action Party’s (PAN’s) candidate, I don’t know if he has managed to formulate any kind of proposal; he just looks at the audience and smiles with his eyes. He who keeps his hands clean can better wash the plates, that is what the PAN’s candidate proposes. What we are proposing in the Other Campaign is the complete opposite of this. First, we are not selling a product, not even a candidacy, a party or a national product. Rather, what we are doing is trying to build is something else from below, and this other thing is completely radical in its difference with what is happening up there.”

He alludes to something that is always in view but which many people pass over: “It is not about convincing different people of the impossible; anyone who is below knows that as his or her misery progresses, so progresses the wealth up above. If there is a pattern we are finding in our tour through Morelos, it is this: residential areas and big shopping malls, and right next to this the deepest misery and desperation. In this way the conquista — as we say, a War of Conquest just like 500 years ago — becomes more and more brutal and bloody. As we say, as if the rich didn’t have enough, as if six, seven houses, cars, vacations in other countries, good cloths and all that didn’t satisfy them and they still wanted more.

The Zapatista illustrates: “And so what happens is that there are people that have a lot of money, and they say, ‘we can sell them things at high prices.’ But there are also people with little money, and one would think, ‘well, they will at least leave them alone.’ But they want all the money we have as well.”

He touches on sensitive issues: “So, there is this line over on the side of politics from above that says, ‘gamble everything you have,’ even if it is very little, on the hope that someone up there can resolve your problem. And when that bet needs to be made again every three or six years, the result for us is that we have less and less money in our pockets, at suppertime we have less food on the table and that food is of lower quality. But now, in addition to this, a new kind of destruction and death appears that wasn’t here before, and it is particularly painful in Morelos, which has always been emblematic for its natural wealth. The water, the forests and the air have in fact been converted into more commodities. That is why Morelos is being settled, not by big landowners such as those that Zapata rebelled against in earlier times, but with tourist developers and real estate entrepreneurs. Where there were once haciendas and later ejidos (communal farms) and communities, residential zones, shopping malls and tourist centers are being erected over communal lands.”

Again he utilizes irony and humor: “We might think that capitalism is going to take care of nature at least to be able to enjoy it, but capitalism is so stupid, and its top representative here is (Governor) Estrata Cagui… Cajigal… Caguijal, we’d say, because he is just fucking it all up (cagando in Spanish) all the time in his rush to make money,” he said, unleashing side-splitting laughter among the crowd.

Marcos reveals the relationship between the politicians and the capitalist system: “It is all about making money, it doesn’t matter what is getting destroyed, and it doesn’t matter that this destruction even goes against their interests sometimes. If someone thinks that capitalism is somehow rational, when the process of destruction runs rampant as it is doing now, everywhere, that person realizes that it is not rational at all. Capital is a big, stupid criminal.”

He argues: “We could make the effort to try to convince capital to be more rational, to think things through better, to not be such an idiot. And so, there is another line with regards to this zone destruction that the country is becoming, which says, ‘we are going to try to humanize capitalism, to rationalize it, to make it good.’ That is the proposal that they are playing with up there.”

But Marcos emphasizes: “We who are in the Other Campaign think that this is useless, that it is not going to produce any results because capitalism’s basis is in its origin. Just as at was born spilling blood, sludge and shit, so it has grown up and so it continues developing.”

“We Are Not Talking About Switching Governments, but Rather Switching Systems”

“So, we say, ‘we are going to do something else,’ we as Zapatistas and we together with all of the organizations, groups, and collectives that are in the Other Campaign, families that have appeared here, individuals such as those that have shown up, we’re betting on the hope that down below we are going to find many small groups, because the success of the electoral marketplace depends on the fact that there are people voting for someone. They are fighting over millions of people and we are talking to ten, fifteen people when sometimes, as one compañero was saying, we were expecting 100 and then suddenly a whole crowd shows up from someone else. It’s great! We are betting on this and everyone feels that his or her struggle is very small, that it is not enough to oppose that which is very large. The Other Campaign says, ‘yes, we are small but if we are able to unite all of this strength we won’t be so small anymore, we won’t be so few, and, above all, we won’t have to be separate.”

The Zapatista spokesman personalizes things; he is direct: “That is what the Other Campaign is trying to do: we are going to listen to the people, we are going to find them and we are going to find that which is ‘other.’ We have already, in other states, met the ‘other’ church, and here we are speaking to the ecclesiastical communities that have given off so much light and continue to shine in Morelos. Once, there was a man, don Sergio Méndez Arceo (the late bishop of Cuernavaca and a pioneer of liberation theology), who we might say synthesized and concentrated this light and never doubted. He could have been like (ultra-rightwing bishop of Mexico state) Onésimo Zepeda, but Sergio Méndez Arceo chose to be Sergio Méndez Arco. He decided not to be a minister or preacher for a church that was in the service of the powerful and preached resignation to the poor.”

Marcos provides details on how the movement is being built: “What we are saying is that we are going to unite this other church with the other gays and lesbians, with the other workers’ movement, with the other peasant farmers’ movement, with the other student, youth, women’s and Indian peoples’ movement, and we will find that two paths open for us beginning this year, in 2006: the path that leads to the destruction of our land and of us as Mexicans, or the path that makes possible the construction of something else, of another country.”

Delegate Zero shares one certainty: “What will end up marking us, defining us, will be the product of this massive listening at a national level with the people from below. That is what is going to say what we are, what we want, and where we’re going.”

He assures the people: “That is why the Sixth Declaration from the Lacandon Jungle starts with a basic definition, which is: we are against those from above; they are our enemies. We do not want to change them or humanize them, or tell them not to be so cruel or give them courses in humanitarianism. What we want is to destroy them and those who serve them, the political parties.”

“When the Sixth Declaration and the Other Campaign defines its enemy, it defines its horizon. We are not talking about switching governments, but about switching systems, at when the time comes to switch systems, everything else comes as well: changing land ownership, changing ownership over politics, defining what politics does, and among other things defining what to do with religion, with the belief that each person has or doesn’t have, and this begins to produce other effects as well.”

He dispels some uncertainties: “We already know what we don’t want. We don’t want this system because it gives pain to everyone, and charges them for it, too. That is the most absurd thing about this year’s elections: they are selling us pain and then they are charging us for it, and they will keep charging us for the next six years if we let them. But we who are in the Other Campaign won’t let them.”

He arrives at the heart of the issue, the marrow that sustains this movement. “We are talking about an other politics, and that is what is at stake here. All of us, all these political organizations of the left and other movements are here to make an other politics and we trust the people to understand that this is different and the value it has, no matter that person’s size, if that person is and old man or woman whom no one respects, if it is a boy that everyone scorns or push to the side because they think he has no judgment, it doesn’t mater if it is an indigenous person who can’t speak, read or write; the important thing is one’s heart and our goal of building a new country.”

He offers straightforward analysis: “The Other Campaign’s call would not be so dramatic if it didn’t go through what it is going through right now. We say; ‘we are not talking about a long-term project.’ Up there, the sectors of the moderate left, so moderate that they have crossed into the right, the intellectuals, say, ‘yes, what those from the Other Campaign are planning is very pretty and good, just like Gandhi and ancient Christianity, and that is what will happen in a hundred years, but right now we need to resolve this and this.’ No, the country won’t last that long. Our call is so dramatic because we say: ‘if we, if the others that we are don’t do what we have to do, there will be nothing left of what we see right now, nothing left of that which we fight for.’”

The subcomandante makes commitments: “This is what we are proposing: what is going to happen, we will all see it no matter how old we are. It is not something that is going to change throughout many years and that perhaps our children or grandchildren will live to see. Rather, it is something we have to do; we have to see why it is necessary as we all make ourselves actors in this process. We make ourselves its conductors.”

He invites those listening to make the movement theirs and to fight for this space through communication: “We must enter the Other Campaign and win our space there, construct it and defend it as women, as children, as young people, as elderly people, as Indian peoples, as workers, as students, as teachers, as homosexuals, as lesbians, as whatever each person is… We have to conquer that space, defend it and convince the Other Campaign of our existence. And we wage that conquest in two ways, with the fist and with the word, and the Other Campaign has chosen the word.”

“At this step, just as you have given us the gift of your word, from now on we ask that you also give us your ears in order to listen to others.”

Click here for more Narco News coverage of Mexico

Lea Ud. el Artículo en Español

Legga questo articolo in italiano

- The Fund for Authentic Journalism

For more Narco News, click here.