“Other Loves” in the “Other Campaign”

Oaxaca’s Queer Community Looks for Common Ground with the Latest Phase of Zapatista Struggle

By Mark Swier

The Ricardo Flores Magón Brigade, Reporting for Narco News

March 24, 2006

On his “Other Campaign” stops through Mexico, Zapatista Subcomandante Marcos regularly invites the participation of workers, farmers, indigenous peoples, women, youth and elders in constructing a national anti-capitalist campaign, “from below and to the left.” But perhaps alone among nationally-recognized political leaders he adds gays and lesbians – what he frequently refers to as the community of “other loves” – to the list of people who fight for a new Mexico and who the Zapatistas seek to ally with in a larger struggle. He has been met along the campaign trail by a broad spectrum of the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender and Queer (LGBTQ) community, a vital sector of allies who have shown support both organizationally and individually to the “Other Campaign” and its goals.

In fact, the EZLN has a long history of drawing connections between the struggle for dignity and survival of indigenous people in Chiapas and movements for liberation around the world. There are plenty of beautiful words that stand as evidence. The poetics of Marcos have referenced queer movements at different times for the past 12 years, last year even challenging Italian soccer giant Inter Milan to a match, claiming that the Zapatista squad would be representing with a lineup of queer and transgender players.

However, even in the “alternative media” very little attention has been paid to the relationship between the Mexican queer community and the Zapatista struggle. The Other Journalism decided to begin our coverage of “other loves in the other campaign” in the majority indigenous city of Juchitán, Oaxaca, where Marcos visited on February 6, and where a visible and very “out” queer and transgender population has long played a significant role in the city’s social, cultural, economic and political life.

The Isthmus

Sexual diversity in Juchitán has been a noted topic for some time, and the area has become a hot-spot for anthropologists and gender enthusiasts of all types. It is a colorful, passionate and mystifying place for its diversity and difference, and there is a lot to show for the decades of work by queer and transgender community members.

In any community, the words people use to describe themselves depend on who is asked, but all are meaningful marks of identity and history. Queers in Juchitan use words like puto and gay to describe male same-sex attraction, and embrace words like travesti to describe gender variance through cross-dressing. But no other word symbolizes Juchitán’s diversity like the word muxe. The word is said to be an adaptation of the Spanish word “mujer,” for “woman.” Many have described muxes in English as effeminate gay men or transvestites. Muxes are seen as male at birth, but given the social space to choose muxe identity during childhood, to identify with characteristics traditionally seen as feminine and experiment with gender presentation. Muxes are involved romantically with men, and publicly present a gender spectrum ranging from effeminate masculine to living fulltime as “female.”

However, muxes have their own unique cultural and historical characteristics that non-indigenous understandings of gender — which often only recognize two expressions: male or female — tend to lose sight of. Muxes represent a third gender, and are only one example within an ancient history of indigenous, other expressions of gender and sexuality. That history in the Isthmus is a rich and complex one, and the large visibility of muxes there provide an inspirational example of queer struggle for dignity against the homophobia and transphobia of so much of the world.

A great deal has been written about this other-gender visibility, to study and share this community with other parts of the world, but a lot of the writing has failed to place this work in a broader context of movements for justice and change. There is a history of studying the experiences of muxes as purely cultural phenomena, and of de-politicizing and under-emphasizing the role of the “simple and humble people who fight” in shaping this history. Academics, who have been willing to pay for interviews, have often been interested more in making a name from the cultural “interestingness” of others than building trust and links between movements.

This project of the Other Journalism had to deal with that history. It wasn’t as simple as showing up in Juchitán – the Isthmus region’s queer epicenter – and finding trannies and queens walking the streets in “EZLN” embroidered ski masks (although that came later).

Getting to know community members in the days before the arrival of the Other Campaign delegation to Juchitán reinforced the importance of building relationships, recognizing the complexity of social, cultural and political realities, and of letting peoples’ stories speak for themselves.

Celebration Culture

The huge range of perspectives on social and political issues in the queer Juchiteca community reflects the depth of an area that has benefited from many decades of queer organization. Velas, community celebrations of neighborhood patron saints, have been a venue for acceptance and visibility for queer Juchitecos and Juchitecas for decades. The organization of velas has evolved to include the gay and muxe communities at all levels.

I hung out at a local bar for an afternoon, where the constant flow of patrons reflected the range of sexuality and gender expression. I met and observed rich and poor queers, straight macho men, travestis and muxes, but notably few biological women who weren’t serving drinks. Juchitan is also well known for the autonomy and financial independence of women, who control the local market-sector economy, dealing in goods such as crafts, textiles and fish.

As I talked with Angel Vega Abregos, an elder muxe community member, in the bar, he spoke about culture and leadership in the community. “All the fiestas in our region have a gay presence. Our culture of parties and celebration is intertwined with social life, and their isn’t a vela without gays and muxes.”

For Angel, the gains of the muxe community haven’t necessarily been political, although they have been fought for and defended. He has been involved with Las Intrépidas (The Intrepid Ones), the oldest muxe organization in Juchitán, which started the Vela de las Auténticas Intrépidas 30 years ago. “The Intrépidas didn’t form to be a political movement,” says Angel “They wanted to strengthen their culture, their presence, to have velas. We’re not getting help from political parties or the system. We’re trying to survive and have a good time while we do it, building a community and defending it because we love it. I love my pueblo; this is paradise to me.”

But the relationship of political parties to the velas in general, and the muxe community specifically, hasn’t been a hands-off one. Velas cost money, and lots of it. The local Intrépidas vela every November 20 costs upwards of $10,000, and backers include former mayor César Agosto of the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI in its Spanish initials).

Éli Bartolo at the Juchitán arrival of Delegate Zero Photo: D.R. 2006 Mark Swier |

Although there have been notable independent initiatives, such as local muxe activist Amaranta Gomez’s close but unsuccessful 2003 bid for Congress, for people such as Éli there are larger and more pressing concerns about how to raise the consciousness of the broader community through political education, about the motives of some traditional leaders, and about how to develop stronger grassroots leadership. Looking at some of the history helps to provide the context for these concerns.

Over the past 40 years, the LGBTQ community itself has gone through incredible change, as it has gained acceptance and visibility. In the 1970s, when television became more widely available, the queer community was exposed to a host of new Western, non-indigenous ideas about sexuality and gender. Some of the television fashion shows introduced new ideas about queer expression. Before television there had not been the same connection between muxe identity and travesti expression – presenting publicly as female. This created a generational shift between older and younger muxes. Amaranta Gomez writes that, “Chatting with muxe yoxho (adults over 50) friends they mentioned that for them cross-dressing is quite a new issue, because in their time it would have been seen as something too risky.” In the 1970s muxes began presenting publicly full-time as women.

Paradise Lost?

These changes didn’t happen without backlash. Éli Bartolo and other community intellectuals have been committed to criticizing institutional homophobia in Juchitán; to teaching community members not to mistake visibility for liberation. “Here in Juchitán, homophobia is more subtle… the middle class doesn’t accept gender variance. This is in part because of the process of westernization through the school system. Furthermore, homophobia is a value external to indigenous communities. It’s an imposition of a system of values and anti-values, and one of the anti-values of the West is homophobia.”

With all the vastness of the gay and transgender presence in Juchitán, noticeably absent is the participation of queer women not born as men. “The other thing we see in ALL of our social spaces is hatred and fear of lesbians,” said Éli. “They are totally excluded, considered sick and incomplete. And this of course also brings us back to the issue of sexism. When we are talking about gender and sexuality and liberation in the Isthmus, we are often talking only about muxe and transvestite culture.” Éli emphasized the need to ally with women’s groups and lesbian organizations as fundamental to moving forward any vision of movement building amongst the muxe community.

According to Éli, the idea many outsiders have of Juchitán as some genderrific fantasy is just that – fantasy. Although the closet doors in Juchitán have been thrown open in many ways, in the minds of Éli and other activists, the reality of homophobia cannot be wished away. Certain velas prohibit entrance to travestis. There are occasional isolated cases of street harassment and violence, systematic misogyny, homophobic and non-critical learning cultures in schools. “The family can be extremely accepting, but in the university, it’s a homophobic atmosphere…and generally these messages are spread from the top down, from the middle and upper class.” Save for a few exceptions, travestis and muxes still experience an overall exclusion from the political process and power structure. This underscores the importance of building power outside of that system. “Paradise does not exist,” says Éli, referring to Juchitán’s popular image as a “queer paradise.”

Work: “We Are Not Surviving”

There are other possible explanations for the higher degree of travesti visibility and acceptance among poor and working class communities. Debunking the common myth of the Isthmus as a matriarchy where mothers simply enjoy having a muxe around to “take care of them when they’re older,” Juchitecos and Juchitecas described the role of economics in shaping muxe identity and family structures.

Fellina Santiago Valdivieso in her Juchitán hair salon Photo: D.R. 2006 Mark Swier |

Amaranta Gomez notes that acceptance of muxe family members, although not always a smooth road, is a particular facet of Zapotec indigenous culture. She describes the process as a “collective discussion mechanism on ‘delicate’ issues” that is taken on as a community and acts as a “supportive structure that helps us resolve internal and external problems.”

Fellina ties an analysis of economic shifts into her understanding of what is needed to make change in Juchitán. “Questions of production are really important to me and the survival of my family because my father is a campesino (peasant farmer). We are not surviving. On a wide scale, farmers don’t have access to the production of our own resources… there is plenty of land, and enough people are trying to produce food, to grow crops, but the economic system forces people into selling their goods, exporting.”

Her experience naturally informs her vision of a more healthy community. “Communities that are well organized and have worked to maintain their own production of food and resources don’t face the economic necessity of migrating to find work in the United States. If I can work my land to cultivate tomatoes for myself, well, I’m going to cultivate them. But the government is giving no support to farmers to work their lands, the economics are set up to serve someone else, and so people have to buy their food at the supermarket.” Fellina’s vision condemns neoliberalism in a way that offers some clear opportunities for building ties with the Other Campaign.

“An Expanse of Need”

The impact of AIDS on queer communities in the Isthmus has, as elsewhere, been a site for a lot of organizing, and creates possibilities for political and social mobilization. Oaxaca’s queer community rallied together to fight for its survival and created institutions out of mutual concern. Organizations springing up in the mid-90s have played a vital role in advocating for more resources for AIDS direct care, medications and treatment. Groups such as Las Intrépidas Contra el SIDA (The Intrepid Ones Against AIDS), Gunaxii Gundanabani (Love for Life), and the Binni Laanu (Our People) Collective drew from already-existing networks to provide AIDS prevention education. Las Intrepidas Contra el SIDA started out of the larger vela community when a group of muxes from the Intrépidas basketball team – helped by the Oaxaca City-based Common Front Against AIDS — put together an AIDS prevention-themed drag show that was warmly received by communities around the state.

Out of this history comes a strong legacy of collective work, which created queer social and cultural networks. But there is also a history of inter-organizational and interpersonal baggage, and Eli and others question what long-term gains have been made in terms of political power. In a community that has never had enough material resources to begin with, in a state widely known as one of the most corrupt in Mexico and which also bears the brunt of brutal NAFTA policies, valuable organizations and networks have been affected by competition.

When asked about the roots of local organizational problems, Angel said: “We have a leadership crisis. We have leaders with no conscience, people who try to benefit financially from representing our community, people who have publicly outed others who are HIV-positive.” Fellina agreed, “I want to see the development of grassroots leadership that doesn’t seek to benefit from the struggle of others.” The divisions that competition for organizational resources creates are a barrier to the type of unity the Other Campaign proposes.

“For the past 20 years AIDS has divided and devastated our community, directly killing our people and creating an expanse of need that didn’t before exist. But also, it created indirect barriers like fights over organizational funding and personal divisions,” reflected Éli Bartolo.

These issues are playing out in Juchitán and across Oaxaca, and reflect the many relevant discussions among radical movements worldwide about funding and the role of nonprofit, often bureaucratic nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) in social movements. The Other Campaign is raising questions about what opportunities exist from outside, from below and to the left of these standard modes of operation. Not that NGOs don’t have a role to play. But rather, the dialogues are asking questions, such as, what resources do communities have right now to build stronger movements, without looking somewhere else?

Building Leadership

One thing that many people cited as necessary in Juchitán is a long-range vision of developing critical consciousness and leadership.

Marina Meneses with her son Amilcar Photo: D.R. 2006 Mark Swier |

She suggested this be undertaken through a process of “seeking out the needs of other groups, collecting proposals as to what they need, and then working to support them in the development of consciousness and self-determination. It means a process of accompaniment, to develop capacity and create networks.”

Maria’s son Amilcar, is a 16-year-old student, musician and media activist. He spoke of the importance of involving youth in this process, the frustrating effects of the generation gap, and offered some strategies for how to engage. “I would like a stronger media alternative. There is a leftwing political show on television, but you can only get it if you pay to have cable. Developing consciousness through political education is important for youth, but it needs to be in a format that people will be interested in.” Amilcar spoke of the need for adults to listen more to the concerns and ideas of youth.

Thinking of some of the five-hour assemblies that characterized the Oaxaca City preparations for the arrival of the Other Campaign, I wondered what kinds of youth-oriented groups exist in Juchitán. “There are cultural groups here that include media and art in their work,” said Amilcar.” “CRECI (the Regional Ecological and Cultural Council of the Isthmus) has put on some good community forums.” Another local cultural organization, Los Galácticos, showed two excellent films in the Zócalo (city square) later that night about Juchitán’s vela culture and struggles to defend forms of youth creative expression.

Many travestis like Julio Fuentes Martinez are committed to child development and education work. “I am a pre-school teacher, and that’s my vision – to be better at what I do, to invest in the growth of the children here in the Isthmus.” Although he shared the analysis of every other person I talked with — that travesti social organization is not specifically concerned or engaged in political work — he was interested in the prospects for dialogue that the Other Campaign represents. “Indigenous struggle for liberation and respect, these are ideas that we share. But we need opportunities to talk. We’ve been working for 30 years to build a community in which we can express ourselves freely. We are defending our identity and have things in common, but we don’t have any relationships built up with the Zapatistas.”

After Marcos’ speech in the Juchitán Zócalo, I asked one of the muxes I had met the day before what he and his friends thought about Marcos’ uncharacteristic (and especially notable here in the Isthmus) omission of any references to “other loves.”

“Well, Marcos is from Chiapas, and he was just speaking for his community.”

This response reflects the general confusion I encountered in the streets about the goals of the Other Campaign, and a general unawareness of the politics behind Marcos’ fame. Several people highlighted the depoliticized nature of Juchitán queer culture. Quipped Julio, “Marcos’ movement is a struggle and a war. Ours is a struggle and a party.”

It might seem easy to think that a struggle for indigenous survival in adjacent Chiapas would immediately resonate in Juchitán, where, according to the film Velas de Juchitán by Los Galácticos, 50,000 of the 80,000 residents speak the indigenous Zapotec language. However, the relationship between regional affiliation and ethnicity is complex. Many in Juchitán first identify as Juchitecos and Juchitecas rather than as indigenous or Zapotec.

Among the people I spoke with there is an understanding that queer folks’ livelihood, safety, visibility and community aren’t due to the support of the PRI or “politics as usual.” The strength of the queer community in Juchitán has come from social and cultural networks outside of political parties. However, this has not necessarily translated into organizing to expand these gains. There is a frustration amongst some activists at the lack of critical political consciousness amongst the community, but also an understanding of the ways that queer identity has been disconnected from an analysis of power and politics.

If many of Juchitán’s travestis have already “fought for their right to party” and are apathetic about politics, Éli Bartolo believes that is all the more reason to start early. Like Julio Martinez and Marina Meneses, he has channeled a majority of his energy into child development and critical education. Early in his career Éli worked with philosopher Mathew Lipman on developing his Philosophy for Children program. He currently works as a principal, is finishing a PhD, and is mentoring the professional development of three muxe teachers – former students of his who are now in their mid-20s.

Many people I met in Juchitán cited the need for public dialogue, creative expression of cultural identity, and political education as vital to the process of linking with the Other Campaign and building stronger grassroots, queer-left liberation movements. Awaiting Marcos’ speech in Juchitán on Saturday February 3, the crowd was given a taste of what that looks like in practice, all at once.

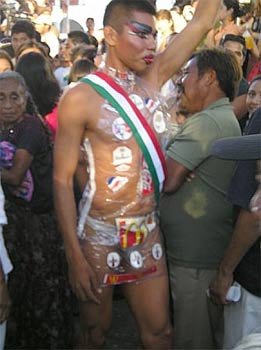

Miss América visits Juchitán

We were paid a visit by “Señorita América” a gorgeous drag queen decked out in transparent plastic and gold pumps, made up in the green, white and red of the Mexican flag with matching sash, and holding a sign displaying the names of Mexican political parties She ran through the crowd for several minutes, tailed by photographers and cops and capturing the fascination of all. The see-through mini left nothing to the imagination, save for the adorning trademarks of neoliberalism – McDonalds, Pepsi, KFC and Coke – which were stuck to the exterior of the dress. Creating a perfectly poignant spectacle, she moved quickly through the crowd and disappeared.

Señorita América Photo: D.R. 2006 Mark Swier |

Lukas is a member of Danza Gabiá, a regional collective working “to listen to our traditions and respond creatively to the challenges imposed by globalization, neoliberalism and de-stabilization of our land.” Using music, dance and visual performance art as tactics, Danza Gabiá creates a public dialogue bridging regional and ethnic culture, sexual identity, generational change, and political resistance. Lukas and other collective members were part of the crowd during Subcomandante Marcos’ visit to meet with political prisoners at Tehuantepec Prison. Danza Gabiá’s work represents a creative and bold synthesis of identity, culture and resistance, and the group plays many roles: artists and performers, educators and organizers. Lukas’ work embodies the building of bridges between communities and cultures, and is a sign of hope for things to come.

Oaxaca City: Back in Black (Fishnets and a Purple Wig)

Returning to Oaxaca’s Central Valleys in advance of the Delegate Zero’s arrival to the state capital, I felt energized and inspired by the broad range of people I had encountered in the Isthmus. I felt hopeful about the work being done, about the clarity with which people illuminated their critiques, concerns and hopes, and about the long-range vision of people to defend culture in the face of empire. But I hadn’t yet been able to tap into a discourse between radical queers and Marcos directly.

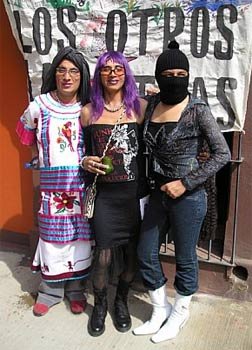

Fortunately, I had met Leonardo Tlahui in weeks earlier. Tlahui is a queer artist, writer and organizer who had been active throughout the planning process for the Other Campaign in Oaxaca City, and is one of the founders of the Nancy Cardenas Sexual Diversity Collective in Oaxaca. Nancy Cardenas was a pioneering freedom fighter for queer liberation in exico, and was taken as the namesake of the group in part to make visible the struggle of the country’s lesbian women. The collective uses art and performance, media activism and education to promote sexual health and fight institutionalized sexual and gender violence. Colectivo Oaxhappen, a sister project in which collective members are involved, hosts a weekly radio show, “Zona Rosa,” Thursday nights from 7 to 8 o’clock on Radio Planton 92.1 FM.

Leonardo Tlahui (center) with members of the Sexual Diversity Collective Photo: D.R. 2006 Mark Swier |

Dressed in black fishnets and a dazzling purple wig, Tlahui stood up and spoke about the history of queer revolutionary struggle. “With the homosexual critique of society comes a political struggle in the first person when one takes the body as a space for struggle in defence of rights and dignity. We have made desire into a space for autonomy.”

Tlahui called to mind specific organizations and history, and then called to task the Zapatista Subcommandante: “The left, too, continues to have its own homophobia. From this place, we ask for an explanation for what happened to our compañero Octavio Acuña, assassinated in the city of Querétaro. He was an activist, a psychologist, and a gay man. And also here, in front of Delegate Zero, we ask him that whenever he speaks of struggles that he be inclusive. In this tour you have been on you have forgotten about us a little. Here we are, and we are also of rebel spirit.”

The cheers and applause were a tangible affirmation of the courage and importance of the collective and its work, and the timeliness of the message. According to Enkidu magazine and other publications, Octavio Acuña was one of five queers killed in homophobic crimes in Querétaro in the month of June alone.

Later that night, in the main plaza in the center of the city in front of a couple thousand more people, Tlahui again repeated the call to recognize the existence and contributions of queers in society and in the struggle for freedom and liberation. After waiting through hours of men speaking long and loud, Tlahui’s speech came directly before that of Delegate Zero. However, this time the applause was better described as thunderous.

More than Words

Marcos responded directly to Tlahui’s message, affirming publicly a commitment to the continued struggle against homophobia and alongside movements for sexual and gender liberation. During his short speech he named constituents and allies with whom he had been in dialogue during his time in Oaxaca, and there was a humorous but revelatory moment as Marcos referred to the community of “gays, lesbianas, and transgénicos” — switching the Spanish word for “transgender” with the word for “genetically modified” — and then corrected himself, laughing bashfully with the crowd at his own mistake.

Names are important, but queer folks in Oaxaca are clear that it takes more than just naming allies to build genuine solidarity between movements. And real trust can’t be built without being vulnerable enough to make mistakes. Marcos’ simple error reflected the space that the Other Campaign dialogue is opening up for Mexican movements, to listen to one another, to learn from mistakes and move forward together. More importantly, the vision and courage displayed by Tlahui and the Sexual Diversity Collective that night in the Zocalo in Oaxaca City marked a historic moment for the queer community in Oaxaca.

In the invitation to take part in the Zapatistas’ new Other Campaign, in the plenary meetings this past Fall 2005, and subsequently as the campaign has gotten underway, the visibility and participation of gays, lesbians and “other loves” has been noticeable. This has been significant not only because the historic sectors of revolutionary movements in Mexico (workers, students and campesinos) have excluded or ignored queer liberation politics, but also because beyond lip service, there hasn’t been an opportunity previously to build connection and dialogue in such a way. One of the six points of the Other Campaign addresses this directly. “These [traditional categories of left organizations] remain important, but there are people who do not identify with them but have the right to a space in political organization.”

The Zapatistas have always used words as part of their arsenal against extinction. Marcos, in his position as a media liaison, has worked to reach out to a broad range of allies in this initial stage of the Other Campaign. He has shown a willingness to listen and learn from the struggles and suggestions of communities of “other loves.” Beginning next fall, a more in-depth process of movement and capacity building will move forward the Campaign, as EZLN representatives fan out across the country to build and organize with different communities for months at a time.

Queer Oaxacans in the Isthmus and the state capital are showing an investment in this process.

This commitment is manifest in ongoing critical analysis, and in the identification of needs, resources and issues around which people are organizing. They are using both long and short-term strategies that can be linked with broader national campaigns, including development of critical consciousness and education; grassroots leadership and organizing; working within the NGO structure to provide vital resources to communities while criticizing that same structure when necessary; building coalitions; developing youth power and leadership; media activism; preserving cultural identities and art forms to create public dialogue; and politicizing already-existing cultural networks.

It is a commitment not just to fighting for recognition but also to transforming society.

Mark Swier has been active as an organizer, educator, friend and ally in different movements for social justice in the United States and Mexico and has worked in the field of sexual health for the past several years.

Click here for more Narco News coverage of Mexico

- The Fund for Authentic Journalism

For more Narco News, click here.