Don Marcos of La Selva vs. the Mega-Windmill of Capitalism

Confronting the Greedy Grabbers that Covet Oaxaca’s Isthmus of Tehuantepec

By Al Giordano

The Other Journalism with the Other Campaign in Oaxaca

February 9, 2006

“…the true knight-errant, though he may see ten giants, that not only touch the clouds with their heads but pierce them, and that go, each of them, on two tall towers by way of legs, and whose arms are like the masts of mighty ships, and each eye like a great mill-wheel, and glowing brighter than a glass furnace, must not on any account be dismayed by them. On the contrary, he must attack and fall upon them with a gallant bearing and a fearless heart, and, if possible, vanquish and destroy them.” – Don Quixote (Chapter VI), by Miguel Cervantes

FEBRUARY 2006; LA VENTA, OAXACA, MEXICO: Seven windmills were raised toward the sky in this small farming and ranching town in 1994. Drivers and riders along the Pan-American Highway might mistake these tall, white generators for what the Mexican government and Spaniard investors called a pilot project for a clean, quaint, source of electricity. When the wind blows, all these giants of capitalism can see is gold. And they’ve got their picks and shovels thrust into the air to mine it.

Photo: D.R. 2006 Annie P. Warren |

But a problem erupted for the Greedy Grabbers on their way to world domination via this anorexic stretch of América: The families that farm more than half that swathe of earth have so far refused to sign away the rights to 700 hectares of their lands. And a fight is brewing between two winds: one from above, the other from below and gusting to the left, both of which understand that the wind that wins this Isthmus will have a strategic advantage in all the battles to come.

This is not about windmills, Zapatista Subcomandante Marcos thundered on Monday morning across this windswept plain. “It is about giants.”

The greedy grab for the Isthmus of Tehuantepec – the narrowest stretch of land in Mexico – is a mega-project by Capital and State that does not stop at windmills. It also includes new highways and oil pipelines connecting the ports on both oceans, an expanded hydroelectric dam in Jalapa del Marques along the way, tourist Meccas to replace small fishing communities between Salina Cruz and Huatulco and a new zone for maquiladoras – those cheap-labor mills that generate power not from wind but from human muscle and bone along the US-Mexican border – that will exploit the poverty of the workers that the mega-developments displace from their lands and the natural resources they cultivate.

And so it is to this breezy plain that Zapatista “Delegate Zero” came on Monday morning to harness the wind that only human hands, and not machines, can tap: that of rebellion. “You are not alone,” he told yet more communities of fighting (read: still human) people throughout the Isthmus. In La Venta’s town square he said, “We will fight with you against these windmills.”

“There is no solution up there,” said Marcos, pointing toward heaven. “This time, yes, we will beat them.”

“La Venta No Está en Venta”

The Other Journalism arrived in this town, twenty minutes outside the city of Juchitán, two days before Marcos’ visit, to a meeting in a humble one-room headquarters of the local small-scale cattle ranchers, and interviewed, filmed, taped, and took photos and notes of their grievances and their reasons for refusing to rent their lands to the windmill giants

Some locals testified that they don’t like the noise the seven current generators make and fear what the din of 500 machines will do to their eardrums. Others hate the spill onto farmlands from the 400 liters of oil that each generator must utilize. Others don’t like the “rental” terms – 13 pesos (a dollar and twenty cents) a day per hectare – and others recall that promises made by the developers of the first seven windmills were later broken. “They came,” recalls local citizen Alejo Girón about what happened when the first seven windmills were installed, “telling lies, promising 300 to 500 pesos a day per hectare, but once the mills were up they paid only two pesos (20 cents) per day, and only on days when the windmills generate electricity.” (The aero-generators don’t work 60 percent of the time, when there is either too much or too little wind.) “We saw the same broken promises in the 1960s when an experimental irrigation project was supposed to bring us water, only to see seventy percent of the water from that dam go to the state oil refinery, and now we don’t have water here.”

Others, still, invoked a World Trade Organization treaty that states that indigenous peoples have a right to honest information about development proposals on their lands, and note the complete absence of that info from the Federal Electricity Commission (CFE, in its Spanish initials) and the eight foreign companies that wish to develop these monsters about the details of the mega-project’s impact on their lives and health. The public is thirsty for accurate information. “We want to hear from people in other countries about their experience with these wind apparatuses,” Jonas Marcos Ayala, a young leader of the fight, told the Other Journalism. “Please ask them to help us to know more.”

“The companies are paying ‘coyotes’ to try to convince other local people to rent our lands to them,” Girón added. “They are trying to trick us on all sides. The latest rumor they spread was that Marcos is coming here to cut down the existing seven windmills!”

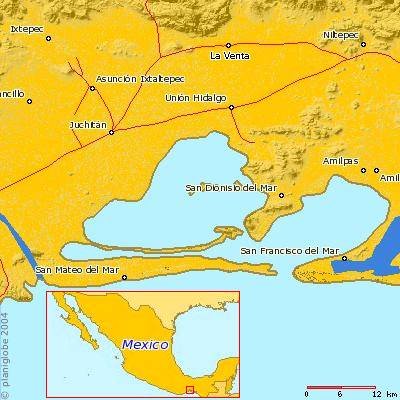

The Isthmus of Tehuantepec on the Pacific coast of Oaxaca. |

Others want simply to keep eating fish. Their friends and relatives in nearby fishing communities along the Dead Sea are up in arms over the Mega-Plan, which calls for the oil-spilling windmills to be constructed atop the sandbar, the natural wall between their two fishing habitats (see map above). The wall regulates the seasonal flow of fresh and salt water back and forth, creating a unique mix of species for fishermen to catch. Ediberto – a fisherman from San Mateo del Mar – came to La Venta on Monday to tell the neighboring community, “We have organized to protest and to say no to the wind corridor. We, the fishermen and shrimp farmers, have seen contamination from oil spills and damage that changes the water currents. We have seen the sand crowded with dead tortoises and fish. What would happen with 2,000 windmills in our region? We haven’t been consulted or informed. This project would bring about the death of our marine species, our jobs and, thus, our cultural identity.”

Mexican investigator Sofia Olhovich: “The project seeks to erect 2,100 windmills in all. Those mills will cover 110,000 hectares” (424 square miles). Photo: D.R. 2006 Annie P. Warren |

Multinational corporations – from Spain, France and the United States – have lined up as brokers to buy and resell the power generated by the Wind Park. Carlos Manzo suggested, “one way that compañeros in those countries could help is to make noise in those countries and cities where those multinationals are located; to inform the public of their plans to destroy our land and culture here.” Those corporations are: Endesa, Gamesa, Iberdrola, Preneal (those four from Spain); Energía del Istmo (associated with Electricité de France); Fuerza Eólica (associated with General Electric); Cader-EHN and Eoliatec.

“The developers are facing real opposition in San Mateo del Mar,” noted investigator Betina Cruz, a Juchitán native currently doing her field work in the region studying the Mexican government’s “Plan Puebla Panama” – of which the Wind Park is a foundation stone – for her scholarship at the University of Barcelona. “The fishing people voted in public assembly not to allow the developers to enter.”

Seen This Movie Before

Anyone who believes the neoliberal hype that any source of electric power that is an alternative to fossil or atomic fuels is therefore “good” – without regard to the project’s size, centralization or who it does or does not benefit – ought to pay a visit to the forgotten town of Jalapa del Marques, on the mountain road between these coastal towns and the capital city of Oaxaca. Until the 1950s, Jalapa was a farming community – primarily corn, beans, and tropical fruits – along a small river. But in 1961 the Mexican government built a dam, flooding the town. During the dry season the steeple of the local church pops over the waterline. Underwater: the homes where the people once lived.

View of Jalapa del Marques Photo: D.R. 2006 Annie P. Warren |

Today, Jalapa del Marques is home to a hodgepodge of displaced peoples, many uprooted from the cultural identity that their indigenous Zapotec, Huave or Mixe parents enjoyed. Others simply fell in here, displaced from other impoverished regions, or as a result of some government-supported land invasions years ago. Many of the streets are paved with concrete, but there are few cars parked or riding around on them. Bicycles are more common. An empty street more common, still. Most of the homes are made of cinderblock. This town of 10,491 citizens was nearly motionless on Sunday; it is after all a day of rest. But when your correspondents returned on Monday, a weekday, it still seemed like a ghost town designed by government planners.

Many live and farm near the vast expanse of the man-made lake that covers Old Jalapa. Others fish the lake. The only industries are farming and fishing, and a few restaurants along the Christopher Columbus Highway (Federal 190) serving mojarra to truck drivers and other passersby. Mexico’s Federal Electricity Commission (CFE) wants to raise the dam now and construct a 20-megawatt hydroelectric plant, at a cost of $22 million U.S. dollars, a project that will displace families from their homes and farmers from the land.

Eteilina Morales Hernández (right) Photo: D.R. 2006 Annie P. Warren |

As in La Venta and the fishing towns along the coast, the people of Jalapa del Marques have received little hard information from the State about how the rise of the lake will impact their lives, but the experience of 1961 is still fresh enough, the dire poverty they live in so evident, that they wouldn’t believe anything the CFE tells them. They already know what the people of La Venta are finding out: that the promises of big energy project developers of more wealth and free stuff to the locals are promises sure to be broken.

Strategic from Above… and from Below

“This region is very strategic for those who are above,” Subcomandante Marcos told a couple hundred adherents to the Zapatista Sixth Declaration who had come from throughout the Isthmus on this final of three days of small meetings and one massive rally. “But it is also strategic from below.”

His message, here as elsewhere, was that the people of La Venta must help the people of Jalapa del Marques, and vice versa, against a common enemy, and that the other social and indigenous movements in the region ought to do the same. “We ask that, as a region, you set up a Commission of Correspondence to keep your people here informed of what is happening… Your struggle will be reported by the alternative media.”

Photo: D.R. 2006 Annie P. Warren Photo: D.R. 2006 Annie P. Warren |

What comes next, kind reader, thus will not merely be a consequence of what happens on the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, but also of whether their grievances find a place in the national and international storm that the tour of Delegate Zero, standing like Quixote or perhaps David before the giants. As these struggles from Chiapas to Quintana Roo to Yucatán to Campeche to Tabasco to Veracruz and now to Oaxaca stack up, the danger that the fights in the last state Marcos visited will be forgotten as new ones come into focus in the 24 Mexican states plus the Federal District yet to come between now and June.

And this places added burden on those of us he calls “Alternative Media” not just to rise to the occasion and coherently report on “the struggle of the week,” but that we also establish lasting communication with the fighters in each place, that we continue to follow the progress, to denounce the repressions, to leave no political prisoner behind, to place the permanent national and international spotlight upon them (because it is more difficult for those in power to extinguish someone in the light than in the darkness).

The task grows more daunting each day, on each stop on this caravan. It towers high above us all. Someone – don Quixote, Delegate Zero, you or I – might even call it a giant.

Today, as your correspondent types, twenty-two members of the Other Journalism, the Narco News team, and the Flores Magón Brigade, have pooled our humble resources and are volunteering our reporting, audio, video, photographic and logistic skills to bring you these true stories. Our efforts grow but so does the giant. Keep dreaming the impossible dream. Send slingshots and rocks when you can. The battle is on. To be continued…

Click here for more Narco News coverage of Mexico

Lea Ud. el Artículo en Español

Legga questo articolo in italiano

- The Fund for Authentic Journalism

For more Narco News, click here.