Guantánamo Bay Military Commissions and the Supreme Court

“These Are the Same Kind of Proceedings the U.S. Has Spent Many Years Condemning When Used by Other Countries”

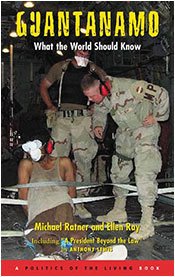

The book Guantánamo: What the World Should Know can be purchased online through the Authentic J-Store at this link. |

By Michael Ratnerand Ellen Ray

Chapter 4 and Conclusion of the Book Guantánamo: What the World Should Know

February 23, 2005

The Commissions

Ellen Ray: You noted earlier that a presidential order authorized military commissions for the trial of noncitizens. Have these been used?

Michael Ratner: It seems that few of these commissions will be employed. When the rules for commissions first came out three years ago, CCR and others thought they would be widely used. They were to be used for trials of alleged members of al Qaeda as well as alleged international terrorists. However, as of May, only two detainees have been charged and only four others designated for commissions.

Ray: What is the government’s explanation for holding commissions rather than conducting criminal trials of suspected terrorists in its custody?

Ratner: The government has labeled the people in Guantánamo enemy combatants. They are using that designation to imply that these people had guns, were found on the battlefield, and are part of a nation-state at war with the United States. They claim they are therefore subject to military law, even though they refuse to apply the Geneva Conventions. But would you call Timothy McVeigh, for example, who blew up the federal building in Oklahoma, an enemy combatant? There is a nice military sound to it, a suggestion that military law applies. But in fact he was a criminal – a terrorist to be sure, but a criminal, not an enemy combatant.

What the United States has done by using the term enemy combatant is to claim such persons can be tried under military law. But military law should not have any application to alleged terrorism. Even if it did, it would still call for trial by court-martial, an established system of military justice, not by military commissions, which are really courts of conviction.

Ray: From what you are saying, you don’t think military commissions can deliver fair trials.

Ratner: The commissions were set up by the president’s Military Order No. 1, issued on November 13, 2001. This order allowed for detentions, but also set up a special justice system for detained noncitizens. The order outlined the basics, and the procedural details were set forth a bit later, in Military Commission Order No. 1 of March 21, 2002, and subsequent orders.

People were quite surprised by the initial order, that the president was using a military order to try alleged terrorists. Terrorism by nonstate actors (those acting on their own, not on behalf of a nation state) is not a violation of military law or the laws of war; rather, terrorism constitutes murder, attempted murder, conspiracy to commit murder, or the crime of terrorism. The September 11 attacks were not part of an attack by a nation-state on the United States and therefore should not be treated under the laws of war.

Even if you believe that there had been a military attack on the United States that justified treating people under military law, this order did not call for regular, competent, impartial commissions or tribunals, such as courts-martial, that are normally used to try violations of the laws of war. Rather, the military commissions are special courts set up by the president to try people for crimes against the laws of war. I do not believe they are legal in light of the Geneva Conventions of 1949 and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. In the last American war-crime trial in the 1970s, Lieutenant William Calley was tried for the My Lai massacre not by a military commission, but by a regular court-martial.

Ray: President Bush has been accused of executive unilateralism in establishing these commissions. Could you talk about how they fit with checks and balances of the Constitution?

Ratner: Our court systems are set up by the legislative branch, not the executive. When military commissions were last used, during the Second World War, there was congressional authority to set them up. In this case, there hasn’t been any such action. These are executive courts, set up by the president to try people the president designates for trial. Congress has been kept in the dark about the administration’s plans for the Guantánamo prisoners, both those in custody and those who might be brought there in the future.

Consider the three aspects of a prosecution. First, one body of the government defines what the crimes are. Second, another body of the government prosecutes the crimes. And a third body of the government adjudicates the guilt and determines the punishment. In our system of checks and balances, each of those steps is taken by a different branch of the government of the United States. The Congress defines crimes. The executive branch prosecutes people for crimes that have been defined by the Congress in courts that have been established by the Congress and the Constitution. The judiciary adjudicates guilt and dispenses punishment.

In this case, the executive has taken all these roles unto itself. The president and the Pentagon have decided that they will define the crimes, prosecute people, adjudicate guilt, and dispense punishment. This is unchecked rule by the executive branch. It dispenses entirely with our system of checks and balances.

Moreover, a convicted person normally has the right to appeal to a higher court. Under these military commissions, the only appeal is to an administrative board (also set up by the executive branch) to the secretary of defense, and then to the president. Here, the president has taken all the functions that normally are distributed widely in our government and put them in his own hands. If that’s not rule by fiat or dictatorship, I don’t know what is.

Ray: So virtually any act anywhere that gives the president reason to believe an alien is involved with an international terrorist organization can trigger a commission. Is that right, and is that fair?

Ratner: Yes, any noncitizen alleged to be an international terrorist can be tried by military commissions according to this military order. The order allows the president simply to designate a person to be detained and then tried. That is unique in our system. Normally the district attorney investigates and presents evidence to a grand jury, and then there is a hearing before an impartial court, set up by the legislature, to determine whether there is enough evidence to bring a person to trial. Now, a person can be bound over to a commission merely because the president designates that person to be arrested, detained, and tried.

There is no check on the president’s power of designation, so he can simply name any alien anywhere in the world, and have the military go pick up that person. This is not hypothetical; the president has already signed such orders. It is an unprecedented power, and it is very frightening that any single person in the world should have this ability.

Ray: Are there legal precedents for these commissions, and do they have rules?

Ratner: The government cites Ex Parte Quirin, of which we spoke earlier. Commissions were, in fact, used quite often during World War II. But those aren’t really precedents for what the United States is doing here.

First of all, the World War II commissions were authorized by enabling legislation passed by the U.S. Congress. More to the point, since World War II, principles of international law, embodied in treaties to which the United States is a party, have prohibited ad hoc tribunals or special commissions like those used in that war. Both the Geneva Conventions, which regulate military law, and the International Convention on Civil and Political Rights say that people can only be tried by regularly constituted tribunals that give full and fair hearings and that are impartial.

By “regularly constituted tribunals” they mean commissions or tribunals that are already set up, not created after the fact for something that has just happened. Ad hoc commissions or tribunals are inherently unfair because they’ve been set up with special rules for the specific purpose of convicting particular people.

Remember, the defendants are designated by the president, turned over to the secretary of defense. They are then investigated by the administration. These judges can decide how much evidence is necessary to convict and what evidence is admissible. This is not an impartial judiciary, as we have in other courts in the United States.

This is not a professional judiciary, as we have in courts-martial. The chief executive designates people to be both judge and jury and determines the rules of evidence. A person charged before a commission is given a military defense attorney, also appointed by the executive branch. The defendant has the theoretical right to a civilian lawyer, except it has to be at his own expense, and so it is rather unlikely that most of those charged are going to be able to hire civilian lawyers. And any civilian attorney would have to have a security clearance, which gives the government veto power over any civilian lawyer.

Another major, fundamental defect in the rules is that the commission may allow any kind of evidence, as long as it’s what they call probative – as long as it has some value, whether or not it would be admissible in a normal criminal trial.

Ray: The former commander of Guantánamo, Major General Geoffrey Miller, has said that three-quarters of the prisoners have confessed to something. How does this relate to the commissions?

Ratner: I am sure that by the time the commissions begin, the government will have all kinds of alleged confessions that in a normal court would be thrown out as coerced, as involuntary, as resulting from torture. But these commissions have no rule about keeping out coerced confessions. It is up to the handpicked judges to decide how much weight or importance to give that evidence. It is all admissible.

The government is also allowed to use hearsay evidence, such as someone testifying that he heard someone say something about someone else; or affidavits from people who can’t be cross-examined. The right of confrontation, which is embedded in our Constitution, will be dispensed with.

In addition, these commissions can be held in complete secrecy – not just when classified information might be divulged, which is normal, but whenever the government decides it is “in the interest of national security” to close the proceedings. Also, although unanimity is required to impose a death sentence, only a bare majority of the judges are needed to convict, even of a death-penalty offense. The fact that a prisoner can be convicted of a death-penalty crime without a unanimous jury is pretty outrageous. In our normal, constitutional system, juries must be unanimous. The administration is easing every single rule meant to protect the defendant.

Ray: What sort of crimes can be charged in the commissions?

Ratner: The Pentagon issued a twenty-page list of possible crimes, all claimed to be violations of the laws of war. None of these crimes have specific sentences attached to them. When a defendant goes before a commission, he doesn’t know whether he might get one year or twenty years or even the death penalty, because no sentence is specified. The only way a prisoner knows he might get death is if he sees seven judges trying him; the rules specify that seven judges are needed to impose the death penalty.

The proceedings violate everything we’ve ever known about justice, about international law, and about military law. They’re really an abomination.

Ray: What is the status of the commissions, and when do they begin?

Ratner: Things are moving, but quite slowly. The order setting up the military commissions was issued in November 2001, over two and a half years back, and there has not been one trial yet. Perhaps they will begin just before the election in November, as some sort of October Surprise.

Some military lawyers thought the government would never actually try anybody in front of such commissions. The rules have changed continuously as major objections have been raised from across the political spectrum. Originally the government claimed the right to wiretap all attorney-client calls. Apparently they might withdraw now from that.

Finally, in August 2003, the president designated six people for potential trial by the commissions. We knew of three of them; one was our client David Hicks, the Australian, and two were from the United Kingdom, Moazzam Begg and Feroz Abassi. We also heard that there were going to be some people from Yemen and Sudan.

But after that designation it became quiet again. No one was charged until February 24, when two of the original six designees were charged. One was Ali Hamza Ahmed Sulayman al Bahlul, a Yemeni said to be an al Qaeda propagandist who had allegedly produced some videos for Osama bin Laden. They charged him with conspiracy to kill and with aiding and abetting in the killing of unarmed civilians by propagandizing for bin Laden. The other, Ibrahim Ahmed Mahmoud al Qosi of Sudan, was charged with conspiracy to commit war crimes. He is alleged to be an al Qaeda accountant as well as a bodyguard and weapons smuggler for Osama bin Laden. But the charges against both of them are not only very vague and broad but also are based primarily on conduct that occurred before 9/11.

What’s wrong with these indictments is that crimes like these can only be committed in the context of an international armed conflict. But there is no international armed conflict here between two nation-states, only a conflict between some members of a group called al Qaeda on the one hand and the United States on the other.

I should point out that as soon as people were designated for these commissions, they were taken out of the regular Camp Delta and put into Camp Echo, a separate camp in which they’re completely isolated and cannot communicate with any other person.

Ray: How do the military lawyers assigned to work on these cases view them?

Ratner: The military lawyers have been aggressive about denouncing these commissions. They consider this situation outside any kind of legal system that they had ever known, and they have spoken publicly about it. They work under William Gunn. Normally a military trial lawyer reports up a chain of command through military legal officials in the Judge Advocate General’s command; but in this case they report to Colonel Gunn, and he reports to the Pentagon, to the office of the secretary of defense, right to civilian counsel in the Pentagon. These are clearly political trials; every decision is based on politics, not on law – that is why decisions are made by civilian appointees in the Pentagon.

Some of the most dramatic statements have come from Major Michael Mori, who was appointed to defend David Hicks. Hicks was expected to be the first defendant to go before a commission. However, as of May 2004, he had still not been charged while two others have been. At a press conference in London, Major Mori complained that the system did not provide “even the appearance of a fair trial.”

His overall criticism is that when you use an unfair system, all you do is risk convicting the innocent and providing somebody who is truly guilty with a valid complaint to attack his conviction. It doesn’t help anyone.

And Mori is not the only military lawyer to have spoken up. Two other lawyers appointed to defend al Bahlul, Army Major Mark Bridges and Navy Lieutenant Commander Philip Sundel, have also been extremely critical of the system. Commander Sundel told a Reuters reporter he did not think his clients had a very good chance to get a fair trial. And Major Bridges pointed out that the standards applied in World War II, which the United States wanted applied here, simply aren’t acceptable today.

The military lawyers also filed an amicus brief in the Supreme Court case in which they made the argument that this commission system is an unfair system for trying people. So they’ve taken fairly dramatic action.

Ray: Have the military lawyers seen any clients yet?

Ratner: Initially, the military lawyers were not allowed to visit their clients, but later some were allowed to visit particular clients. These clients – Hicks, al Bahlul, al Qosi, and the remaining English prisoners – don’t appear to be major targets of the United States. It may be that some of these people have been coerced over a two-year period into giving some kind of statements, and these statements may be false. The government may have expected immediate guilty pleas, with some quick sentences as a way to get the commissions moving. But that was in August, and nearly a year later there still have not been any guilty pleas, so it obviously hasn’t worked out quite the way the government expected.

Ray: How are these commissions viewed in the Muslim world?

Ratner: They are the same kind of proceedings that the United States has spent many years condemning when used by other countries. The United States condemned the use of such a commission or tribunal against Lori Berenson in Peru. They condemned the use of such a tribunal against Ken Saro-Wiwa in Nigeria. For many years the United States has had a strong position against the use of military commissions or military tribunals. Now, under Bush, instead of trying to limit these proceedings in other parts of the world, the United States is creating an example that other countries will follow.

How can all this look to the Muslim world? It is obviously in the interest of the United States to make our country less hated among the peoples of the world – Muslims and others – and the way to do that is not to set up an obviously unfair system of kangaroo courts that try only Muslims. We should have a fair and open system in which people can participate, in which people get a fair trial.

The Supreme Court and Guantánamo

Ray: On April 20, 2004, the Supreme Court heard arguments in the Guantánamo cases. What were the legal proceedings in the federal courts leading up to those arguments?

Ratner: The Center for Constitutional Rights began these cases by filing a writ of habeas corpus on behalf of three Guantánamo detainees in the lowest federal court, the District Court for the District of Columbia. We filed in February 2002, and the case took more than two years to get to the Supreme Court. We were joined by another law firm, Shearman & Sterling, which represented twelve Kuwaiti detainees. Both cases were considered together throughout the proceedings.

We lost the case in the district court. The judge bought the government’s argument hook, line, and sinker and said the court had no jurisdiction to hear the case, that aliens held outside the United States have no right to habeas corpus and no constitutional rights whatsoever. Our clients could not even get into court; their claim could not even be heard.

We tried to argue that because Guantánamo Bay Naval Station is under the complete jurisdiction and control of the United States, it is akin to sovereign U.S. territory. If a member of the U.S. military commits a crime in Guantánamo, that crime is tried by the United States under U.S. law.

The government argued that no American court, nor any other court for that matter, had any jurisdiction over any cases coming out of Guantánamo. The government pinned its argument on the claims that the United States does not have “ultimate sovereignty” over Guantánamo, without ever defining what “sovereignty” means. This will undoubtedly be their argument in the future for holding detainees without court review on U.S. military bases in Iraq, Afghanistan, and elsewhere. These are the arguments that were laid out in the Justice Department memo to the Pentagon a few weeks prior to the first detainees being shipped to Guantánamo.

We believe that a habeas corpus proceeding should be able to be brought in a U.S. court on behalf of anyone being held by the United States anywhere in the world, but Guantánamo in particular ought to be a clear case. The United States is the only legal authority there. The administration’s position – that habeas corpus could only be brought by someone inside the United States – was, we thought, just ridiculous. Still, we knew from our experience representing Haitians detained at Guantánamo in 1991 that the United States was insistent that no court had jurisdiction over Guantánamo. The United States wanted Guantánamo to be a law-free zone. And that is what the District Court ruled.

Ray: You then appealed that decision; what was the result?

Ratner: We appealed the decision of the District Court to the Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit, and we lost on the same grounds. It was a devastating defeat, and some of us thought it was the end of the road. We couldn’t get a court even to say it had the right to hear our arguments. Nevertheless, we asked the Supreme Court to review the case. We had no right to demand they take the case, only to request that they hear it. We figured they would never take the case for two reasons: one, we were still living in the time of the so-called war on terrorism, and in such times the Supreme Court doesn’t like to review executive decisions. And, secondly, we had already lost in the two lower courts so there was no compelling political necessity for the Court to take the case.

Ray: By that time, the prisoners had been held for a year and a half, and as far as is known, little or nothing of value had come out of the interrogations; Osama bin Laden had not been captured; no vast stockpiles of weapons of mass destruction had been found. How did the passage of time affect the public’s perception of the cases?

Ratner: We had tremendous support by the time we were preparing our petition for review in the Supreme Court. Editorial writers across the country were asking what was going on in Guantánamo, why were there no hearings, how long can you hold people without a hearing or charges, contrary to the Geneva Conventions, how long can a situation like this go on?

Even if you believed that the government needed to interrogate these people, a year and a half had gone by, and there was no indication that anything significant had been learned in Guantánamo. By this time any intelligence would be quite out of date. Critical stories were coming out about people’s treatment there. Some prisoners had by now been freed, and it transpired that many of them had been picked up wrongly, based on bribes or something else, from small villages where there had been no fighting.

In addition to the changing perceptions about the value of the Guantánamo interrogations, there was also a shift among conservatives, who worried about this level of unchecked executive authority. The idea that the government could simply pluck people from anywhere in the world and hold them indefinitely began to worry conservatives.

So when we asked the Supreme Court to review the case, we had an extremely broad group of amicus (friends of the court) urging it to take the case. They included survivors of the World War II detention camps for Japanese-Americans; former prisoners of war; former military people, including a general; former diplomats; and many other people across the political spectrum. The case developed a certain legitimacy it did not have at the outset; people were getting nervous about this previously unheard-of executive overreaching.

And then, after we filed, all we could do was wait, though with little hope. It was a complete shock to us when, in November 2003, the Supreme Court said they would review the case of the Guantánamo detainees. However, they limited their review to a very narrow but crucial question that goes to the heart of whether the United States is a society governed by the rule of law: “Whether United States courts lack jurisdiction to consider challenges to the legality of the detention of foreign nationals captured abroad in connection with hostilities and incarcerated at the Guantánamo Bay Naval Base, Cuba.” The court is thus considering whether its doors should be closed to people detained by the United States at Guantánamo. If we win, and the Supreme Court says the doors are open, it would then send the case back to a lower court to determine just what rights people held at Guantánamo have.

If we lose, it would effectively mean that no Guantánamo detainee could ever test his detention. It would be a disaster for a country that claims to adhere to the rule of law. In effect, it would also mean that no noncitizen detained by the United States anywhere in the world outside of the fifty States could test the validity of his or her imprisonment in a court. Detention by the executive branch would be unchecked by any judicial review.

The administration saw this decision – even to review their position that no court had jurisdiction – as a slap in the face. High officials were really shocked by the notion that the Supreme Court could review, and perhaps prohibit, decisions that the president, the commander in chief of the war on terrorism, was making. They believe that the president can do whatever he wants in that war, and that no court in the world can tell him otherwise. The fact is that a majority of this Court, a relatively conservative Supreme Court, may have been offended by the notion that the administration could decide what actions of the chief executive the judiciary can and cannot review. Indeed, this is the essence of what federal courts do – review the legality of executive and congressional actions. The Court may have been concerned about overreaching by the president, about the question of whether a metaphorical war on terrorism justifies the wholesale abrogation of constitutional rights everywhere.

Ray: What sort of maneuvers did the administration try after Supreme Court review was granted?

Ratner:It was obviously very nervous and wanted to show the Court that it could be trusted. Shortly after review was granted, it announced they would be releasing up to 140 detainees in the next few months. This would be the first mass release. Of course, another reason for these releases is that Guantánamo has become a symbol of American lawlessness around the world, and the leaders of many countries were getting pressure from citizens who are working to free their countrymen. So the administration was throwing them a bone, hoping to lessen international pressure and attempting to combat the hatred the United States has engendered, in part because of Guantánamo. The administration was obviously scrambling. It even gave David Hicks – one of our clients designated for a commission – a military lawyer.

Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Detainee Operations Paul Butler said that each individual case had been assessed by an integrated team of interrogators and behavioral scientists and regional experts, that individual detainees’ cases were assessed according to the threat they posed to national security interests of the United States and our allies. A few weeks after the Supreme Court arguments the Department of Defense established these panels and issued regulations for their governance. They also proposed yearly in-house reviews of each case to see if anyone no longer “dangerous” could be released.

Ray: What can you say about these assessment panels?

Ratner: There are serious problems. The new policy would create a three-member board of military officers to conduct an annual review of each individual detained at Guantánamo and make a recommendation about the continued utility of detention. But the final decision as to detention is made not by the proposed review board but by the designated civilian official (DCO), who is appointed by the president and works for the Department of Defense. Detainees can be ordered kept in detention, despite the panel’s recommendation, if the DCO’s opinion is that the detainee “remains a threat to the United States,” or “if there is any other reasonthat it is in the interest of the United States and its allies” for the detainee to remain in detention. In other words, any reason at all can justify the detentions, even if the review panel decides otherwise.

These panels are totally one-sided. Everyone is working for the Department of Defense, and the person being assessed has no lawyer or spokesperson or advocate of any kind to say that, for example, they are using material based on coerced statements from other prisoners. These reviews don’t offer any real legal protection.

However, these new rules and the other machinations all suggest that the administration was scrambling so they could go into court when the case was argued, and point out that they were doing something. They were telling the court, “You don’t have to take action in this case. We are going to process people. We are going to do something with these people.” And this is exactly what they said in their briefs.

Had we not been granted review, the government would have done absolutely nothing. They would not have moved an inch on Guantánamo. It is only because of this review – and the outcry both in the United States and around the world – that there has been any movement at all.

Ray: The United States claimed in the Supreme Court that it does not have sovereignty over Guantánamo, but could a prisoner at Guantánamo bring a case in a Cuban court against the United States?

Ratner: Well, the lease says complete jurisdiction and control is in the hands of the United States, so it’s unlikely that a person detained in Guantánamo could bring any kind of suit in Cuba or anywhere else. And yet, while the United States claims Cuban courts would have no authority over this, at the same time, if a person tries to bring it to a U.S. court, as we have, they claim that complete jurisdiction and control is not sufficient for there to be U.S. jurisdiction because ultimate sovereignty resides in Cuba.

Ray: The United States formulated this doctrine during the first Bush administration, when Haitian refugees were rounded up and imprisoned in Guantánamo. You were directly involved in the lawsuits challenging those actions. Could you tell us more about them?

Ratner: The major issue for the government in those cases was making sure that Guantánamo remained a law-free zone where the detained Haitians had absolutely no rights under international law or under the Constitution. They went out of their way to ensure that that was the case.

Ray: And at that time, the United States managed to keep the U.S. courts from reaching a definitive ruling on the question of court jurisdiction over Guantánamo. But they have not been able to keep the question out of court forever, have they? How could the cases currently in the Supreme Court finally resolve this issue?

Ratner: Well, the cases in the Supreme Court squarely raise the question of whether any American court has jurisdiction over detainees in Guantánamo. There is also a separate issue: can U.S. officials detain any noncitizen anywhere in the world, whether in Guantánamo or elsewhere, and be outside of the court system? If a person is picked up and detained at a U.S. military base in Abu Ghraib, or Diego Garcia, or Bagram, is that person outside the court system? They should not be.

But even if the answer to that is yes, Guantánamo is quite different, as the United States has complete jurisdiction and control over the base. As the U.S. Navy states on its Web site about Guantánamo, it exercises “the essential elements of sovereignty over Guantánamo” and is the “supreme authority” there.

So what the Supreme Court will resolve, finally and presumably definitively, at least for a period of years, is whether or not non-U.S. citizens detained at Guantánamo have the right to to challenge their detentions.

U.S. officials are very clear on why they chose Guantánamo, as opposed to some other place. In Pakistan or Afghanistan, for example, there would still be (at least in theory) courts of that country where a person could challenge a detention. People publicly detained on Diego Garcia could presumably go into a court in the United Kingdom – which owns the remote island – to challenge their detentions. If you know the name of a person held in Bagram, you can conceivably go into a court in Afghanistan and challenge the detention. But if you keep people in Guantánamo, under the U.S. theory there’s no court in the world that can take those cases. That is why people are in Guantánamo.

Ray: By the time this book comes out, the court will have ruled on the jurisdiction issue in your case. I would like you to anticipate, first, the worst possible ruling the Supreme Court could give, and second, the ruling you would desire.

Ratner: The worst possible ruling the Supreme Court could give is that no U.S. court has jurisdiction to decide any case of a noncitizen held outside the United States, whether in Guantánamo or not. In other words, the Supreme Court could decide that an alien picked up and held by the United States in a detention facility outside the United States and who has never had a significant relationship to the United States has no right to come into an American court.

That’s saying that the United States can pick up noncitizens anywhere in the world, bring them anywhere they want outside the United States – Guantánamo, Bagram, South America, Egypt, wherever – keep them there indefinitely, and these people can never go to an American court to complain about it.

The Court could issue a more limited ruling that would be good for the Guantánamo detainees. It could say that because they’re in Guantánamo and Guantánamo is under the complete jurisdiction and control of the United States, the Court has jurisdiction over cases from Guantánamo.

At that point it might simply decline to rule regarding people kept outside of Guantánamo. A ruling as to detainees in those places would be unnecessary to a decision in this case. No detainees from outside Guantánamo are before the Court; those cases would be left for another day. The middle ground would be this second, limited holding.

However, the most positive decision, the third way, and the one I think comports with the Constitution and international law and justice, is that any person, noncitizen or citizen, held in detention by the United States anywhere in the world can bring a writ of habeas corpus in a U.S. court to test the legality of his or her detention.

Ray: Assuming you win the Guantánamo case in the Supreme Court, what happens next?

Ratner: Well, the case would most likely go back to the lower court, the district court, which would need to determine the lawfulness of the detentions. The lower court would determine what rights the detainees have and the type of hearing they are entitled to in order to test their detention. The government would argue that the Rumsfeld panels are adequate; we would argue they are not. This could all take a long time. I hope the attention brought to the plight of the detainees, the public outcry, the pressure from other countries, in combination with favorable court rulings, will speed up the processing and release of the detainees.

Ray: What about Jose Padilla and Yaser Esam Hamdi? What are the legal implications of those citizen-as-enemy-combatant cases, and what are the best- and worst-case scenarios?

Ratner: We should discuss them separately. Hamdi was a U.S. citizen supposedly picked up on a battlefield in Afghanistan and brought to Guantánamo, where they discovered he was a U.S. citizen. Then they put him in a Navy brig in South Carolina. Because Hamdi is both a U.S. citizen and physically in the United States, there is no question about jurisdiction; the U.S. courts are open to him. However, there is considerable question about what rights he has and the proper scope of review of his detention. They still haven’t given him a lawyer to litigate his case. They’ve given him one to talk to, but not to litigate the particular facts in the case.

The real question is whether he can challenge the government affidavit that describes why he is considered an enemy combatant, that is, that states he was found on a battlefield in Afghanistan with a weapon. The government is saying that all he can do, all his lawyer can do, is argue that the affidavit does not allege enough to make him an enemy combatant, which is ridiculous. He should, as a U.S. citizen being held by the United States, be able to argue that the United States has no right to designate anyone an enemy combatant or, on the basis of such a designation, to prevent him from challenging the substance of his detention in court, to challenge the underlying facts and to examine the witnesses against him.

So the worst ruling in Hamdi would be for the Supreme Court simply to say, We agree with the Justice Department and with the lower court that he is not allowed to litigate the factual sufficiency of the affidavit and that the affidavit based on hearsay that he was picked up in Afghanistan is sufficient to hold him indefinitely in a military brig without access to a lawyer.

Padilla is, in my view, a harder case for the government than Hamdi. Padilla was picked up getting off an airplane in the United States wearing civilian clothes. The government claimed he was a “dirty bomber.” Like Hamdi, he is also being held in a brig in South Carolina, and like Hamdi he has been denied an attorney. The government has submitted an affidavit saying he has some relationship to al Qaeda, and he hasn’t been able to challenge that affidavit in any meaningful way.

But in the Padilla case, the intermediate court, the Second Circuit Court of Appeals, ruled in his favor. They said that he had to be released within thirty days or tried by a regular criminal court, because in their view, if you’re going to hold an American citizen in the United States you need a special statute allowing you to do so, and the Bush administration never got that authority from Congress. So two of the three judges on that court ordered his release.

The worst ruling in his case would be, first, that the government is right that he can’t have an attorney and can’t challenge his affidavit; and second, that a special statute requiring authorization from Congress to hold American citizens within the United States is not applicable in his case because the useof-force resolution against al Qaeda passed by Congress after 9/11 is, in fact, such a statute.

So there are two ways to lose those cases and both are quite harmful. In both cases the government essentially denied the habeas corpus petitioners the right to challenge what the government says in an affidavit, denied them the right to an attorney, and claimed there is no need for specific statutory authorization to hold them. Obviously, if Hamdi and Padilla, as U.S. citizens, have no right to an attorney or to meaningfully challenge their detentions, the detainees in Guantánamo will not have such rights either. So the scope of the relief they are given will be relevant to what ultimately happens to the Guantánamo detainees.

The best result in both Hamdi and Padilla would be that they are entitled to attorneys as soon as they’re detained, that those attorneys have a right to meet with their clients privately and to examine the facts in the case, that they have a right to submit evidence to the courts, and that the government cannot use hearsay affidavits to claim that they’re somehow enemies. Those would be very, very important decisions. And finally, it would be extremely important if the Supreme Court said you simply cannot use military law in these situations of alleged terrorism, but must treat people under normal criminal procedures.

Conclusion

Ray: Do you have any final thoughts about Guantánamo and what we have been discussing?

Ratner: Guantánamo represents everything that is wrong with the U.S. war on terrorism. The Bush administration reacted to 9/11 with regressive and draconian measures worthy of a dictatorship, not a democracy. They imposed the very measures they condemned in other countries: indefinite and incommunicado detentions, refusal to justify these detentions in court, disappearances, military commissions, torture. It was a descent into barbarism. The practices at Guantánamo spread to Iraq and other U.S. detention centers around the world. The U.S. government has obviously lost any moral ability to challenge such actions when taken by other countries. It has endangered people all over the world, not only by its own conduct but giving its imprimatur to inhuman treatment, which will embolden other countries to do likewise.

It has taken a thousand years to secure human dignity and basic rights for all. The struggle to do so is marked by moments like the signing of the Magna Carta in 1215, the Habeas Corpus Act in 1679, the U.S. Constitution, the Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen, the Geneva Conventions, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, and the Convention Against Torture. The United States has now treated these landmarks of human progress as naught. Of course, there has never been complete adherence to these documents, but rarely, if ever, has there been such open, notorious, and boastful violation of fundamental protections as at Guantánamo.

But this is not to say that I am pessimistic about the chance of returning to sanity, enlightenment, and the rule of law. For the last few years, we have been in a long dark tunnel with no fresh air and no light. The president and his cohorts, who have brought us to this state, are in trouble: trouble in Iraq and trouble in Guantánamo. That even the Supreme Court appears to think so is a cause for optimism. We are at the beginning of what will be a long struggle to repair the damage that the government has inflicted on us all.

Michael Ratner is President of the Center for Constitutional Rights. He served as co-counsel in Rasul v. Bush, the historic case of Guantánamo detainees before the U.S. Supreme Court.Under Ratner’s leadership, the Center has aggressively challenged the constitutional and international law violations undertaken by the United States post-9/11, including the constitutionality of indefinite detention and the restrictions on civil liberties as defined by the unfolding terms of a permanent war. In the 1990s Ratner acted as a principal counsel in the successful suit to close the camp for HIV-positive Haitian refugees on Guantánamo Bay.

He has written and consulted extensively on Guantánamo, the Patriot Act, military tribunals, and civil liberties in the post-9/11 world. He has also been a lecturer of international human rights litigation at the Yale Law School and the Columbia School of Law, president of the National Lawyers Guild, special Counsel to Haitian President Jean-Bertrand Aristide to assist in the prosecution of human rights crimes, and radio co-host for the civil rights show Law and Disorder.

Ellen Ray is President of the Institute for Media Analysis and the author and editor of numerous books and magazines on U.S. intelligence and international politics. She is co-editor with William Schaap of Bioterror: Manufacturing Wars the American Way and Covert Action: The Root of Terrorism, both published by Ocean Press in 2003.

Guantanamo: What the World Should Know on Narco News:

The Inquisition Strikes Back (Book review by Jules Siegel)Chapter 1: Guantánamo Bay and Rule by Executive Fiat

From the Narcosphere:

The World Knows: Council of Churches Calls for Rights for Guantánamo Inmates

by Benjamin MelançonDoe v. Bush: Suit Filed on Behalf of Guantánamo Prisoners

by Benjamin Melançon“Reaction Forces” beat and humiliated Guantánamo prisoners

by Benjamin MelançonJudge: Guantánamo prisoners can fight for their freedom in court

by Benjamin MelançonWhy the World Must Know: Publisher Margo Baldwin on Guantánamo

by Benjamin MelançonGuantánamo: Detainee torture in US operated prisons

by Andrei Tudor

- The Fund for Authentic Journalism

For more Narco News, click here.