“Officials In the U.S. Government Have Committed War Crimes”

Reporting the Truth on the Savagery of Guantánamo Bay

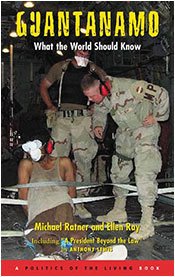

The book Guantánamo: What the World Should Know can be purchased online through the Authentic J-Store at this link. |

By Michael Ratner and Ellen Ray

Introduction to the Book Guantánamo: What the World Should Know

January 28, 2005

EDITOR’S NOTE: This is the first installment of Michael Ratner and Ellen Ray’s book Guantánamo: What the World Should Know, which Narco News will be publishing, serially, in its entirety. Readers can expect new installments each week of this important work, and can purchase copies of the book at Salón Chingón, with proceeds going to The Fund for Authentic Journalism.

Interviewer’s Preface

It was late summer 2003 when I agreed to ask my friend Michael Ratner to participate in a book project for Margo Baldwin of Chelsea Green Publishing about the legal plight of the prisoners held in the ultra-secret facilities at the Guantánamo Bay Naval Station in Cuba. Michael, a human rights attorney and the president of the Center for Constitutional Rights (CCR), was, as he explains below, a Gitmo veteran of sorts. Our passionate publisher Margo convinced us to use an interview technique to explain a very complicated, developing situation, as had been used in the book by William Rivers Pitt and Scott Ritter, War on Iraq, which she helped publish.

Few people outside the Pentagon knew anything about what was happening at Guantánamo. Shortly after 9/11, thousands of Muslims and Arabs, all allegedly very dangerous terrorists, had been rounded up, and hundreds, from more than forty countries, were transported to Guantánamo. The conditions they were being held in were unknown; the base was totally off-limits to journalists, researchers, and human-rights activists. The Pentagon had classified who was there, why, how many of them there were, where they came from, and most importantly, what was being done to them.

As one of the few civilians knowledgeable about Guantánamo, Michael Ratner, along with his colleagues at the Center for Constitutional Rights and elsewhere, began representing several of the prisoners whose families had managed to learn of their plight and seek legal assistance. But aside from a few prisoner letters and an unusual International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) report describing the mental state of the prisoners there as universally “in despair,” we had little direct information about the treatment the prisoners had received. At first our manuscript was replete with terms like “alleged brutality,” “claims of torture,” “possible deaths by beating.”

Events then overtook us. Between March and May of 2004, as we were conducting the interviews that comprise the text of this book, the world was confronted with the photos of the sadistic torture and mistreatment of Iraqi prisoners at Abu Ghraib. Allegations became facts. Initial denials of any systematic misconduct, or of approval or direction by military officers or Bush administration officials, began to dissolve in a swirl of contrary evidence, which continues today.

In the fall of 2003, Major General Geoffrey D. Miller, at that time the commander of Guantánamo Bay Naval Station, was sent to Iraq by the Pentagon’s intelligence chief to “Gitmoize” Abu Ghraib prison there. This meant “facilitating” interrogations by having low-level military police guards “soften up” the prisoners, “enabling” the intelligence interrogators to get confessions, apparently by any means necessary, ignoring the Geneva Conventions.

The connection between Abu Ghraib and what many suspected had gone on at Guantánamo became clearer as the military was forced to release some of those detained at Guantánamo, whose subsequent accounts echoed the Abu Ghraib abuses. Further reports by the ICRC, the Pentagon, and the State Department, White House memos, and endless interviews and congressional hearings document the horrendous abuses about which the entire story has yet to be written.

The other manner in which events overtook us was that the Supreme Court granted review of the lower court cases relating to the legal rights of the prisoners at Guantánamo and the two U.S. citizens being held in military prisons as “enemy combatants.” This book has gone to press after the arguments but before the Court’s decisions. As the reader will note, we have had to speculate on those results.

Regardless of the legal impact of the Supreme Court’s rulings, it is clear that the remaining prisoners will need whatever protection can be provided by having the eyes of the world upon their captors. We hope this book will play a small part in helping its readers to understand the horrors that are being committed by the U.S. administration and to take action against them.

Interviewee’s Preface

I have had a lot of experience with Guantánamo. In the early 1990s, I was one of the counsel from the Center for Constitutional Rights representing Haitian refugees imprisoned in an HIV camp at Guantánamo Bay Naval Station in Cuba. I visited my clients and the base a number of times. It was a dreadful experience, a desert outpost where inhuman treatment, even of refugees, was common practice. It was in the litigation regarding those refugees that the U.S. government, initially under the presidency of George H. W. Bush, formulated its legal position that Guantánamo was a law-free zone. According to the first Bush administration, the Constitution simply did not apply at Guantánamo.

Although our team of lawyers ultimately prevailed in the case, the administration was insistent that Guantánamo remain a law-free zone, preserving a territory in the world where the U.S. government was free from court scrutiny, free from the constraints of the Constitution, and free, sadly, to violate people’s rights with impunity.

Yet in January 2002, when I read that the first prisoners from the Afghanistan war and from President Bush’s “war on terror” were being sent to Guantánamo, I was still shocked. I knew what it meant. It meant not only a tough legal fight to protect their rights, but also that there would be no check on the treatment of those detained. They would be imprisoned without any right to see, speak to, or write to lawyers; without visits from family members; and without any charges specified against them. The administration was painting all of them – falsely, it turns out – as the “worst of the worst,” ordering their imprisonment until the war on terror was over, a period that might easily run some fifty years.

Whether the Center for Constitutional Rights should get involved was not the easiest of decisions. But we saw these detentions as an extremely serious assault on our fundamental liberties. We believed strongly that the president, acting unilaterally, did not have the right, even as commander in chief in a war, simply to designate people for detention, hold them incommunicado, deny court review, and throw away the key. At that time we could not even imagine the abuses that have now been revealed.

We began to round up other lawyers to work with us, but it was not an easy task. The only lawyers willing to help were antideath-penalty lawyers who were used to representing unpopular clients. And we got plenty of hate mail, especially early on, for our representation of the Guantánamo detainees.

As is explained in this book, we lost our case at the trial level, in U.S. district court, and we lost our appeal to the circuit court. But to our great surprise, the Supreme Court granted review, and arguments were heard on April 20, 2004. It went well, but there will not be a decision until after this book goes to press. I am optimistic that the courthouse door will not be closed to those imprisoned by the United States at Guantánamo and that the Court will reaffirm the principle that we are a country of laws where people cannot be imprisoned at the whim of the chief executive.*

Only days after the Supreme Court argument, the notorious Abu Ghraib pictures were publicly revealed. And it is becoming clear that such abuses, mistreatment, and torture are rampant in other U.S. military prisons – perhaps many others. Our work to expose and stop this is only beginning. Whatever euphemisms they may use – such as “stress and duress” – officials in the U.S. government have committed war crimes. We hope this book will stand as a warning of the risks the United States takes when it departs from the rule of law, from rules of civilized conduct.

I want to thank Ellen Ray, my good friend, who took my files, read and analyzed them, and forced me to sit down to be interviewed. Her husband, William Schaap, a lawyer and editor, also did masterful work on the manuscript. And our publisher, Margo Baldwin, pushed us to make sure our message was as timely as possible.

Joe Marguiles from Minneapolis, a cooperating attorney with CCR, became a key litigator in what ultimately became a Supreme Court case. Two other lawyers who were most helpful early on were Clive Stafford Smith from Louisiana and Professor Eric M. Freedman from Hofstra University. Each of them played a remarkable role as the litigation went forward. I also want to thank Shearman & Sterling and its lead counsel, Thomas Wilmer, a terrific and determined lawyer. And I must thank the British lawyers, especially Gareth Pierce and Louise Christian, and the courageous military defense attorneys with whom we worked.

Finally, I want to express my gratitude to the Center for Constitutional Rights and its lawyers and staff for working so hard on the Guantánamo cases. Attorneys Barbara Olshanky, Steven Watt, and Jules Lobel all played important roles in the litigation. CCR has been instrumental in fighting for people’s rights since its beginnings, when it defended civil rights activists in the south in the time of Martin Luther King, Jr. It has been one of the leading legal institutions fighting for our rights since 9/11. Not only is the Center lead counsel in the Guantánamo cases, but it is representing, in a class action, Muslim and Arab detainees arrested in the Ashcroft sweeps in the United States that followed 9/11, and it is legal counsel to Maher Arar, the Canadian citizen “rendered” to Syria, where he was tortured. CCR also won the first case declaring a section of the Patriot Act unconstitutional. As I write this, in June 2004, CCR has just launched a major case against private contractors allegedly involved in torturing detainees in Iraq and Guantánamo.

* Editor’s note: The Supreme Court did indeed rule in favor of Guantánamo detainees on June 28, 2004, just after this book was originally released. Read the decision here. While a victory for Ratner and his legal team, the decision still left many issues unresolved…

Michael Ratner is President of the Center for Constitutional Rights. He served as co-counsel in Rasul v. Bush, the historic case of Guantánamo detainees before the U.S. Supreme Court.Under Ratner’s leadership, the Center has aggressively challenged the constitutional and international law violations undertaken by the United States post-9/11, including the constitutionality of indefinite detention and the restrictions on civil liberties as defined by the unfolding terms of a permanent war. In the 1990s Ratner acted as a principal counsel in the successful suit to close the camp for HIV-positive Haitian refugees on Guantánamo Bay.

He has written and consulted extensively on Guantánamo, the Patriot Act, military tribunals, and civil liberties in the post-9/11 world. He has also been a lecturer of international human rights litigation at the Yale Law School and the Columbia School of Law, president of the National Lawyers Guild, special Counsel to Haitian President Jean-Bertrand Aristide to assist in the prosecution of human rights crimes, and radio co-host for the civil rights show Law and Disorder.

Ellen Ray is President of the Institute for Media Analysis and the author and editor of numerous books and magazines on U.S. intelligence and international politics. She is co-editor with William Schaap of Bioterror: Manufacturing Wars the American Way and Covert Action: The Root of Terrorism, both published by Ocean Press in 2003.

Next in “Chapter 1: Guantánamo and Rule by Executive Fiat”:

Guantánamo Explained… The Center for Constitutional Rights’s Involvement… The End of the Rule of Law… Rule by Executive Fiat… Enemy Combatants

Guantanamo: What the World Should Know on Narco News:

The Inquisition Strikes Back (Book review by Jules Siegel)

- The Fund for Authentic Journalism

For more Narco News, click here.