Guantánamo Bay: Testimony and Case Details

U.S. Lies About “Humane” Treatment Revealed By Relatives and Released Detainees

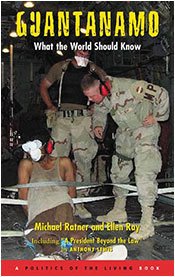

The book Guantánamo: What the World Should Know can be purchased online through the Authentic J-Store at this link. |

By Michael Ratner and Ellen Ray

Chapter 3 of the Book Guantánamo: What the World Should Know

February 15, 2005

False Confessions

Ellen Ray: The Center for Constitutional Rights currently represents two Australians, David Hicks and Mamdouh Habib, and two young men from England, Shafiq Rasul and Asif Iqbal. I understand that those four were your clients in the Supreme Court case. What can you tell us about David Hicks, the first CCR detainee case?

Michael Ratner: Hicks was picked up in Afghanistan, allegedly on the battlefield but by the Northern Alliance, not by Americans. In January 2002, Defense Secretary Rumsfeld claimed that Hicks, an alleged Australian Taliban fighter, was someone who had threatened to kill Americans, one of the “worst of the worst.”

Soon after his capture in Afghanistan, Hicks was beaten extensively during at least one interrogation, and was shackled and denied sleep for long periods. He spent time on U.S. Navy warships, where interrogations apparently took place, and at the Bagram air base, north of Kabul, before being sent to Guantánamo. He has been detained there as an “unlawful combatant” for more than two years without charge.

Ray: Some of the people who were released, among them two of your clients, have either falsely confessed or, as the U.S. military has said, no longer have any intelligence value. What do you think this means?

Ratner: Remember that Rumsfeld called these people the worst of the worst, the hardest of the hard core, people who tried to kill tens of thousands of Americans. And yet we see that even according to their own internal documents, U.S. officials knew that wasn’t the case. Rumsfeld was lying to the American people from the very beginning.

A lot of these prisoners confessed to various crimes and supposedly divulged various sorts of intelligence information. But in fact, after two and a half years of incarceration in cages, with no hope of release, people will say anything if it’s going to get them a meal, if it’s going to stop them from being interrogated, if it’s going to get them a toothbrush. This is well known to anybody who studies confessions. At Guantánamo, one of the rewards for talking is a shower. Another is the opportunity to get some exercise. After two years and two hundred interrogations, any of the most minor creature comforts will get people to say almost anything.

Ray: Some of your clients provide examples of this, don’t they?

Ratner: Yes. Some of our clients who were released were kept in Bagram and then Guantánamo for almost the entire two-year period. The United States showed them videotapes in which they were purportedly depicted with Osama bin Laden.

At first they maintained that it wasn’t them in the videos, but eventually they confessed that it was. These confessions turned out to be utterly false and were obviously coerced by the United States. We know this because eventually British intelligence, under growing pressure in Britain to investigate the prisoners’ claims of innocence, proved to the American government that the men were actually in the United Kingdom at the time the videotape was made.

Some of the released British detainees had been picked up by the troops of a Northern Alliance warlord working with the Americans, Rachid Dostom. They were some of the many thousands of people packed into steel shipping containers in which thousands died; thirty to fifty out of each container of three to four hundred survived.

They then were taken to Sheberghan prison for more than a month of interrogation and treated awfully. Then they were taken in chains, trussed like chickens with goggles over their heads so they couldn’t see, to Kandahar, where they were subjected to very heavy interrogations: forced to kneel, beaten on their backs.

Ray: Some of the British citizens at Guantánamo were not released. Tell us about them.

Ratner: There were nine British subjects at Guantánamo, and only five have been released. One of those still being held, for example, is Moazzam Begg, the son of Azmat Begg, a banker from Birmingham, England. Moazzam Begg was one of six Guantánamo detainees designated for a possible military commission. As of now, he has not yet been charged.

His story shows the administration’s utter disregard for people’s rights. Begg went to Afghanistan with his three young children to be a teacher. Eventually, he wound up helping construct water wells in very poor communities. When the war broke out, he was living in Kabul; when the bombing started, he escaped over the border into Pakistan, where he rented a house. His father was in touch with him and used to talk to him there regularly.

And then one night American soldiers and Pakistani intelligence agents came to his house and in front of his children, grabbed him, stuck him in the trunk of a car, and took him away. He had a cell phone with him, and he called his father, who got a lawyer in Pakistan to file a writ of habeas corpus. The Pakistani government claimed they did not know where he was. Eventually, when the judge was about to hold the interior minister in contempt, it was revealed that he had been turned over to the Americans.

The Americans apparently took him back into Afghanistan, and he eventually arrived at the notorious Bagram interrogation center, a place where we believe torture is being practiced. Begg spent approximately a year in Bagram. We don’t know much about what he did there. His father got one or two heavily censored letters, in one of which he said that he never saw the sun or the moon, that he hadn’t seen daylight for at least nine months in Bagram. Because of the censorship, of course, we don’t know if he was tortured or if he tried to write anything about torture.

After a year in Bagram, he was transferred to Guantánamo, where he remains today. There are rumors that he is in terrible shape, which is one reason his father, an eloquent advocate for fair hearings for the prisoners, has not heard from him since mid-2003.

Azmat Begg says, in substance, “Look, I don’t know what my son did or didn’t do, but the idea that he isn’t getting any kind of trial is outrageous.” The United States claims the prisoners are free to write letters, but Mr. Begg has not heard from his son in many months. He may have been tortured; he may be in no mental shape to write.

Guantánamo as a Model for Iraq

Ray: On May 13, 2004, two of CCR’s British clients sent an open letter to President Bush and some members of Congress. In it, they stated that military officials regularly used humiliating and degrading techniques that led to false confessions. Among the techniques they describe are short-shackling, whereby detainees are forced to squat for hours with their hands chained between their legs and fastened to the floor; being left naked and chained to the floor while women are brought into the room, a particularly humiliating experience for prisoners from strict Islamic backgrounds; and assaults and beatings so severe that hospitalization was required. Can you comment on this testimony?

Ratner: What is amazing to me is that these allegations are consistent with much of what has been revealed about interrogation abuse in Iraq, demonstrating that what was first used in Guantánamo was then used in Iraq. The Red Cross was apparently quite critical of these Guantánamo techniques and has issued a nonpublic report. That report, which a reporter has described to me, confirms what the letter reveals: short-shackling, chaining to the floor, stripping, and stress-and-duress physical positions. This and reports from other former prisoners are pretty shocking, and they certainly confirm our clients’ credibility.

Ray: The government in its brief to the Supreme Court in the Guantánamo cases claimed that the people in Guantánamo were treated humanely. Is that the case?

Ratner: The government, in its brief before the Supreme Court, asserted that the people in Guantánamo were given three meals a day, given medical care, allowed religious worship, given mail, and given Red Cross visits to check on their conditions. But when you go through those five aspects of treatment, as well as others, you can see, based upon what has been publicly revealed, that the detainees were not being treated humanely. The entire operation – everything, from what you eat to where you sleep to what level of prison you’re in – is run by the intelligence people, whom the detainees refer to as Intel. Nobody, not the Red Cross, not even your own guards, really has any power to change anything. It’s all about intelligence and breaking people down and making them talk.

For example, meals are withheld or changed or just plain bad, depending on whether or not they consider you to be cooperating. In one case, a person who was clearly allergic to fish was given fish three times a day. So meals are used not only as a reward, but as punishment.

Secondly, the United States brags that the prisoners are getting better medical care than they got in Afghanistan or in Pakistan; but the prisoners have said that medical care, like meals, is withheld if you don’t cooperate. If you have some kind of pain or you need some sort of medicine, they won’t give it to you unless you cooperate.

The government claims that the prisoners have freedom of religious worship. But copies of the Koran, the holy book of Islam, were frequently stepped on and smashed by prison guards.

The fourth aspect of treatment is mail. The United States claims in its briefs that prisoners can send and receive mail, although censored. But one of our clients has not received a letter for two years. Intelligence officers hold up their mail.

One detainee was told that the interrogators had letters from his family and that he would he get to see these letters only if he cooperated with them, if he talked to them. And so, even though there is theoretically an absolute right to get mail—through the Red Cross and under the Geneva Conventions—prison officials are using deprivation of mail as a hammer to try and get cooperation.

The fifth area is Red Cross visits. Again, the Red Cross is supposed to have access to any detainee it wants to see. However, when the Red Cross visited one of the detainees, they asked his name, and when he gave it to them they said, “Oh, you’re on our list. We don’t get to see you.” What was really going on was the United States not letting the Red Cross see people they wanted to put more pressure on. The United States has now admitted that, with regard to Iraq, it not only hid certain prisoners from the Red Cross, but also requested that the Red Cross give notice of its visits. Like similar actions taken in Guantánamo, this was an effort to avoid detection of its illegal interrogation methods.

So not one of the five things the United States claims in its brief to be doing to ensure humane treatment is really being done.

They had other ways of punishing people and trying to make them cooperate. I was told of one detainee who spoke only English and was put next to Arabic-speaking prisoners, so that he was truly isolated as a way of putting more pressure on him or simply making his life uncomfortable.

Other kinds of misconduct included injections. Detainees have been pinned to the floor by the IRF Squad and given forcible injections. Detainees also said that after every meal they became groggy. They still don’t know why; possibly just to keep them under control, under some kind of sedation.

Each person interrogated was also given a lie detector test. Whether you passed the test determined whether you got certain privileges, what level of prison you were at, whether you got a toothbrush, whether you got a cup to drink your water, what kind of meal you might receive.

The three questions asked in the lie detector test, and over and over during interrogation, were the same for everyone. One: Are you a member of al-Qaeda? Two: Were you trained at the Al Farook training camp? (This is a camp the United States claims was run by bin Laden in Afghanistan.) Three: Were you given any special weapons training while you were at that camp? They repeated those questions constantly.

Even if you passed the test, it did not mean your release from Guantánamo. And although lie detectors are quite unreliable, if you didn’t pass the test you got your beard and your head shaved as a punishment, another attack on the Muslim religion of the detainees.

Other means of harassing people included guards spitting in food, which happened on occasion. Another method of getting people to talk was by using false stories. For example, prisoners were told, “Well, you better talk to us because we were in a cave in Afghanistan and we found Osama bin Laden’s records, and your name was on a list, and you’re one of the five most wanted people in the world right now.” Of course they would never show the list, because no such list existed, and no such cave existed, and no such records existed.

In some cases, they also intimidated prisoners with family photos that had been sent to them. The guards enlarged the pictures and put them on the wall, threatening that things would happen to the prisoner’s family unless the prisoner talked. This is also a form of torture; you are not allowed to threaten someone’s family to make them talk.

I also heard of a rather strange interrogation technique that I didn’t really understand. In one interrogation room there were posters of Palestinian women who had apparently been killed by the Israelis. They were told, “You see what’s happening to your brothers and sisters in Palestine? They’re getting murdered and killed. If you want to fight on their behalf, all you have to do is cooperate with us, and we will release you to go fight on behalf of the Palestinians.” It just didn’t make a lot of sense to me, but then the whole camp doesn’t make a lot of sense to me.

Ray: Possibly the interrogators were trying to gauge sympathy for the Palestinian cause, if there were Israelis among them.

The British

Ray: Nine British prisoners were picked up in Afghanistan and detained in Guantánamo. Five of them were released into British custody in March 2004, and on return to the United Kingdom, they were released in less than twenty-four hours. One of the released British prisoners was Jamal Udeen. What was his story?

Ratner: These rapid releases once the prisoners arrived in the United Kingdom indicate to me that the British detainees were wrongly held, wrongly interrogated, and wrongly treated from the beginning. The British certainly would have charged them upon their return if they had been able to.

Jamal Udeen was thirty-seven years old, from Manchester, England, a father of three. He had gone to Pakistan in October 2001 on his way to Turkey, traveling through Afghanistan. He had a British passport, and the Taliban picked him up at the border, probably thinking he was a British spy. They threw him into a Taliban jail, and when the Taliban were routed, Northern Alliance soldiers came into his cell and took him to the Americans, even though he was obviously a prisoner of the Taliban. Eventually he was taken to Kandahar, and then to Guantánamo. Today, according to one reporter who interviewed him, he walks with a stoop; the shackles bound him so tightly that he is permanently disabled.

Ray: How did some of the British clients find out that they were going to be released?

Ratner: The Red Cross visited them and told them that they would be released. But then the U.S. intelligence guys came in and said, “Look, we want you to become our informants when you go back to England, and inform on the Muslim community, and if you do, we will give you a nice house, all sorts of things. And also we’d like you to sign a confession, because if you don’t sign a confession, you’re never getting out of here.” But they knew they didn’t have to sign the confession, because the Red Cross had already told them they were being released, so they just refused to do so.

This indicates two things. One is that the United States is using this camp not just for interrogation but to create a stream of informants all over the world. The other is that the United States wanted to justify these unjustified two-and-a-half-year detentions by trying, to the very end, to get the detainees to sign confessions. Of course, they also hoped they could get them to become double agents, and, as a former CIA officer told the Washington Post, they wanted them to carry misleading intelligence back.

Ray: What more can you say about the British role in Guantánamo?

Ratner: I should point out that some of these five are considering lawsuits against the British government for its complicity, as well as against the U.S. government. The primary responsibility for this international detention camp is America’s, but other intelligence agencies around the world are working with the United States, both in this camp and in others.

We know from lawyers in England that British intelligence worked with the United States in trying to gain intelligence from the Guantánamo detainees. The British were supposed to be sending diplomats over to help get their citizens released, but in fact British intelligence was working to try to build cases against these people. Their British defense lawyers are now blaming the British government for collaborating with the United States to keep these people in prison.

The problem is not simply the United States. The problem is governments around the world, Great Britain and the United States in particular but others as well, including China using these detention facilities as an unlawful means of extracting information from people.

Ray: Doesn’t this imply that people are guilty until proven innocent?

Ratner: Of course. They have punished innocent people for two years. With any kind of legal hearing, these people would never have been jailed. The government even made the ridiculous argument before the Supreme Court that the prisoners get to tell their side of the story, by being interrogated.

The Afghans and the Pakistanis

Ray: A number of Afghans have been released. What are some of their stories?

Ratner: The stories of the twenty-three Afghans who were released from Guantánamo in March 2004 are consistent with the charge that the United States was detaining the wrong people. One detainee, Haji Osman, a fifty-year-old businessman, spent eighteen months at Guantánamo, and he never learned why. He was released after two and a half years, along with an eighteen-year-old cousin of his, and the Americans simply told him that they were sorry. They even imprisoned an Al Jazeera cameraman from Sudan for two years, for no apparent reason.

The Afghan stories are compelling. Some of those released said after they arrived home that they had been abused and deprived of sleep for weeks at a time. One, a prisoner named Mohammed Khan, said, “They did everything to us, they tortured our bodies, they tortured our minds, they tortured our ideas and our religion.”

Another prisoner, Muhammad Sidiq, a thirty-year-old truck driver from Kunduz, said he had been beaten, first at Bagram and then at Guantánamo. “They covered our faces,” he said, “and started beating us on our heads and giving us electric shock.” For two or three weeks he was going crazy, and then the beatings stopped, although he was often kept in chains. He slept in a place that was nine feet long and seven feet wide, and he could not see other prisoners most of the time.

Another prisoner, Aziz Khan, a forty-five-year-old father of ten, said he was taken because he had some rifles at his house. He was sometimes in chains, sometimes put in a place like a cage for a bird, sometimes kept in a freight container. He said, “Americans are very cruel. They want to govern the world.”

Ray: The United States also released a number of Pakistanis in March 2004. What do we know about them?

Ratner: A man named Abdul Raziq was one of eleven Pakistanis released from the Camp Delta prison in Guantánamo. He had a master’s degree in agriculture and was arrested in Afghanistan while on a preaching mission. They shackled him, sent him to Kandahar and later to Guantánamo. Another Pakistani, Abdul Mullah, a taxi cab driver from a village in Afghanistan, had been picked up for no reason, and he was understandably bitter about his experience. Another twentyfour-year-old returnee, Shah Muhammad, says the experience left him mentally disturbed. He said he tried to commit suicide four times while he was in Guantánamo.

Ray: One of those released, a Spaniard, was sent to Spain for possible prosecution. What is his story?

Ratner: Twelve prisoners were recently sent from Guantánamo to their own countries for possible prosecution. One of them, Hamad Abderrahman Ahmed, was from Spain. Even though he was sent to a Spanish prison, even though he may be prosecuted by the Spanish, he said “he was happy to have escaped the hell.”

In an interview on Spanish radio he said that soldiers in Guantánamo stepped on his head as he lay face down on the ground, stepped on him and tied him up with a thin string that made him bleed. He denounced terrorism and the killing of women and children and said he had nothing to do with al Qaeda.

Ray: What other stories do you know about people in the camps?

Ratner: Well, for example, one person who had been picked up in Pakistan had been taken to Egypt, where he received electroshock treatments, which are apparently quite common there for political prisoners. Some of my other clients have also had such treatments.

Another person who was released about a year after the camp started claimed he was somewhere between ninety and one hundred years old. He was apparently one of the most pathetic sights, old and frail and barely able to get around the camp. He was chained with shackles to a walker. He was incontinent. When he would walk around his cell, or when he was let out for a little exercise, he would just cry all the time.

Some of the people released spoke of others sent to Guantánamo from Bosnia, via some other country, where apparently they were tortured as well. My clients said that the majority of the prisoners had been picked up in Pakistan by Pakistani police, not Afghanistan, and most of them were people who had been turned over for bribes and favors from the Americans. Most of them, almost all of them, were not fighters. They didn’t think anyone was actually a terrorist.

The Children

Ray: Let’s talk about the children. The Pentagon released three children between the ages of thirteen and fifteen who had been detained in Afghanistan on suspicion of fighting there. They were eleven to thirteen when they were arrested. And the Red Cross has said there are more children in Guantánamo. The government tells us that the children were treated very delicately.

Ratner: First of all, keeping children in a detention camp like Guantánamo is completely illegal under international law. The United Nations Convention on the Rights of Children says you can’t do that; you have to begin rehabilitation and send them home immediately. Even if you think they did something wrong, they are still children, and they are to be treated under a juvenile justice system, not kept in a prison camp.

It was only after some complaints got out that the children were moved away from the other prisoners and put into a separate camp, Camp Iguana. But the continued presence of children in any prison camp is really an indicator of the whole outrageous situation there. And the stories of these three children are pretty harrowing.

One of them, Mohammed Ismail Agha, now back in Afghanistan, was probably thirteen or less when he was picked up. He says he was arrested by Afghan militia soldiers and handed over to American troops in 2002 while he was looking for a job. He was in prison for fourteen months as a terrorist suspect, two months at Bagram and then a year in Guantánamo.

He says he was guilty of nothing but looking for a job, and he lost a large piece of his life. It was ten months after his disappearance before he could get a letter to his father, who had been looking for his son all that time. He said, “When I was first captured, I was thinking they would not imprison me for long because I was innocent.” When they took him to Cuba, he thought he would be released quickly; yet more than a year went by. This is a pretty outrageous case, but it fits the pattern of how the United States is treating not just children but everybody in Guantánamo.

Michael Ratner is President of the Center for Constitutional Rights. He served as co-counsel in Rasul v. Bush, the historic case of Guantánamo detainees before the U.S. Supreme Court.Under Ratner’s leadership, the Center has aggressively challenged the constitutional and international law violations undertaken by the United States post-9/11, including the constitutionality of indefinite detention and the restrictions on civil liberties as defined by the unfolding terms of a permanent war. In the 1990s Ratner acted as a principal counsel in the successful suit to close the camp for HIV-positive Haitian refugees on Guantánamo Bay.

He has written and consulted extensively on Guantánamo, the Patriot Act, military tribunals, and civil liberties in the post-9/11 world. He has also been a lecturer of international human rights litigation at the Yale Law School and the Columbia School of Law, president of the National Lawyers Guild, special Counsel to Haitian President Jean-Bertrand Aristide to assist in the prosecution of human rights crimes, and radio co-host for the civil rights show Law and Disorder.

Ellen Ray is President of the Institute for Media Analysis and the author and editor of numerous books and magazines on U.S. intelligence and international politics. She is co-editor with William Schaap of Bioterror: Manufacturing Wars the American Way and Covert Action: The Root of Terrorism, both published by Ocean Press in 2003.

Guantanamo: What the World Should Know on Narco News:

The Inquisition Strikes Back (Book review by Jules Siegel)Chapter 1: Guantánamo Bay and Rule by Executive Fiat

From the Narcosphere:

The World Knows: Council of Churches Calls for Rights for Guantánamo Inmates

by Benjamin MelançonDoe v. Bush: Suit Filed on Behalf of Guantánamo Prisoners

by Benjamin Melançon“Reaction Forces” beat and humiliated Guantánamo prisoners

by Benjamin MelançonJudge: Guantánamo prisoners can fight for their freedom in court

by Benjamin MelançonWhy the World Must Know: Publisher Margo Baldwin on Guantánamo

by Benjamin MelançonGuantánamo: Detainee torture in US operated prisons

by Andrei Tudor

- The Fund for Authentic Journalism

For more Narco News, click here.