Guantánamo Bay and Rule by Executive Fiat

“The United States Is Trying to Overturn One of the Most Fundamental Principles of Anglo-American and International Law”

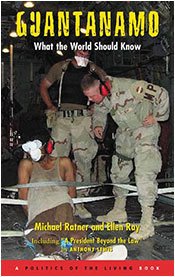

The book Guantánamo: What the World Should Know can be purchased online through the Authentic J-Store at this link. |

By Michael Ratner and Ellen Ray

Chapter 1 of the Book Guantánamo: What the World Should Know

January 31, 2005

Guantánamo Explained

Ellen Ray: Michael, the American military base at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, has been called everything from “an off-shore concentration camp” to a “legal black hole.” What is happening there and why is it so important we have this discussion about it?

Michael Ratner: Guantánamo has become a symbol of much that is wrong with our society. It is a complex of brutal prisons where hundreds of men and boys from all over the world, many of whom we believe are neither guilty of any crime nor pose any danger to the security of the United States, are being held by the U.S. government under incredibly inhuman conditions and incessant interrogation. They have not been charged with anything, they have no access to counsel or the courts, no right to any hearing of any kind, and no idea when, if ever, they will see an end to their plight. These prisons are a symbol of the disdain with which the Bush administration has brushed aside longstanding precepts of international law and civilized conduct. It is indeed a national disgrace.

Ray: To begin this examination of Guantánamo, tell us something about the history of this base.

Ratner: Guantánamo Bay Naval Station, a U.S. military base comprising 45 square miles at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, exists as a result of what one might call the first phase of outward U.S. imperialism (as opposed to inward imperialism, the so-called manifest destiny under which the United States conquered much of North America). For a very long time, the United States had coveted some Spanish colonies – in particular Cuba and Puerto Rico, neither very far from Florida. In 1898, as Cuba was fighting for its independence against Spain, the United States intervened in what became the Spanish-American War under the guise of helping the Cubans defeat the Spanish. A little less than a year later, when the war ended, the United States controlled Cuba, Puerto Rico, the Philippines, and several other former Spanish colonies.

Cuba’s constitution, which was adopted in 1901, included what is called the Platt Amendment, legislation that established conditions for American intervention in Cuba and gave the United States the right to maintain a military base on the island in perpetuity.

Pursuant to the Platt Amendment, in 1903 the United States leased Guantánamo from Cuba. The lease contains several critical provisions relevant to whether U.S. courts have jurisdiction over the base. First, the lease gives the United States “complete jurisdiction and control” of that territory, saying merely that it “recognizes the continuance of the ultimate sovereignty of the Republic of Cuba.” In other words, the Cubans have no authority whatsoever over Guantánamo.

Secondly, the lease can only be terminated on the mutual consent of both parties. Even though Cuba has wanted to terminate the lease since the revolution in 1959, it is unable to do so without the consent of the United States. And the United States can withhold its consent forever.

The lease actually provides for a minuscule rent, some two thousand dollars in gold (equivalent to about $4,085 a year in current U.S. dollars), although the Cuban government has refused to accept any payment since 1959. The United States is technically in default, and has been for many years, because the lease provides that the base is to be used only for a coaling station; but the Cubans have never been able to do anything about this. The base has been used as everything from a holding pen for Haitian refugees to a prison for the Guantánamo detainees – everything except its original purpose as a coaling station.

The United States claims it does not have sovereignty over the Guantánamo base, but in fact it exercises all aspects of sovereignty. For all intents and purposes, Guantánamo is a colony or territory of the United States. A U.S. soldier who commits a crime in Guantánamo – rape, murder, or something else – can be tried by a court-martial in Guantánamo or can be brought into the United States and tried in a federal district court. The applicable law in Guantánamo is the federal U.S. law. The United States has complete control and jurisdiction over Guantánamo, which should give American courts the authority to look into the detentions in Guantánamo.

Ray: In its current incarnation, what is Guantánamo Bay Naval Station, in fact?

Ratner: Guantánamo is something vastly different from what the average American would think of as a prison. Guantánamo is a twenty-first century Pentagon experiment that was, in fact, outlawed by the Geneva Conventions of 1949. It is similar in purpose to the German World War II operations that led to the ban: it is an interrogation camp, and interrogation camps are completely and flatly illegal.

Guantánamo has provided an opportunity for the U.S. government to hold people outside any legal or moral system, with no access to lawyers or contact with family, in dehumanizing isolation, and subject to physical duress, psychological manipulation, and in some cases conduct that may amount to torture. The detainees have no means of asserting their innocence and no means of testing their detentions in any court. In the case that the Center for Constitutional Rights brought, the lower federal courts ruled that the detainees had no right to file a writ of habeas corpus.

Ray: Before we go further, perhaps you should explain just what a writ of habeas corpus is.

Ratner: This is essentially a request to a court to order an official under whose authority a person is being detained to bring that prisoner before the court in order to justify the lawfulness of that detention to the court. It has been a hallmark of Anglo-American law dating back to the seventeenth century, when some British officials were sending prisoners to remote islands and military bases to prevent any judicial inquiry into their imprisonment. Parliament passed the Habeas Corpus Act to prohibit this practice of offshore penal colonies beyond the reach of the law – precisely the practice the Bush administration has revived.

Ray: What purpose does Guantánamo serve?

Ratner: Guantánamo’s purpose is to break down the human personalities of the detainees in order to coerce from them whatever their captors want, to get them to confess to anything, to implicate anyone. Guantánamo is a prison where cruel and inhuman and degrading treatment – even torture – is practiced, and it is utterly illegal.

That is what Guantánamo is and has been for almost three years. The U.S. government admits it is an interrogation camp, though it denies torture is used there. However, the administration admits to using techniques that legally constitute cruel, inhuman, and degrading treatment, which is prohibited under law. Interrogation is why the U.S. administration is depriving all these people of any legal or human rights, why it shaves their heads and keeps them in cages, why they have no access to their families, why in many cases their families may not even know if they are dead or alive.

Ray: Why should American citizens be concerned about Guantánamo and what is taking place there?

Ratner: Americans should care about what goes on at Guantánamo for a number of reasons. First of all, the way we are treating the prisoners there is a scandal, an embarrassment to the people of this country and an outrage to the people of the world. That you can take someone and put him in a prison offshore with no legal rights whatsoever for two and a half years is simply inhumane.

Second, our treatment of these people, who are primarily Muslims and of Arabic ethnic origin, should be a cause of tremendous consternation because of the message it sends to the Muslim world. Guantánamo has become iconic in the Arab and Muslim world; it stands for the United States doing wrong and abusing people.

If we want to live in a safe world, the message we should send is that we will treat people not like animals but like human beings. Although we should be trying to lessen the anger toward the United States within the Muslim and Arab world, we are not doing that; we are, in fact, doing the opposite.

Third, we should care about Guantánamo because we should care about how others are going to treat our citizens. If Americans – soldiers or civilians – are picked up overseas, how do we want them to be treated? Do we want them treated lawfully, in accordance with either criminal law or the Geneva Conventions, or do we want them treated like we are treating the prisoners at Guantánamo? The United States is setting an example for how international prisoners are to be treated, and it is a terrible example.

A fourth reason we should care is what this all means for the future of the rule of law, and for the building of societies that are based upon the rule of law and not on the dictates of kings or presidents. For nearly eight hundred years, since the signing of the Magna Carta in 1215, our laws have insisted that every single human being is entitled to some kind of judicial process before he or she can be thrown in jail. The United States is trying to overturn one of the most fundamental principles of Anglo-American jurisprudence and international law. This is a principle that is found in the Declaration of the Rights of Man, in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and in the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.

We have gone back to a pre-Magna Carta medieval system, not a system of laws, but of executive fiat, where the king – or in this case the president – simply decides, on any particular day, I’m going to throw you into some prison. You are not going to have access to a lawyer or anybody else, or even know if there are any charges against you, or if you will ever be released from this prison. Guantánamo has become our Devil’s Island, our Château d’If from The Count of Monte Cristo.

The consequences of this unilateral abrogation of fundamental law are grave, not merely for the people in Guantánamo and for citizens of other countries, but also for every person in the United States. If we care about civilization and the rule of law and justice, we cannot keep treating people like this. There should be no place in the world that is a law-free zone, no place in the world where human beings have no rights.

The Center for Constitutional Rights’ Involvement

Ray: How did the Center for Constitutional Rights become involved in the defense of the Guantánamo prisoners?

Ratner: It happens that I live very close to the site of the World Trade Center, and like many others I was utterly shocked and distraught after the September 11 attacks.

But early on, my colleagues at the Center and I saw that this act was going to be used by the Bush administration as an excuse for draconian restrictions of our civil rights and civil liberties at home and for expanded U.S. hegemony and warmaking abroad. September 11 has become an excuse – whether in Guantánamo, in Afghanistan, in Iraq, or here at home – for the wholesale infringement of fundamental liberties. For example, by November 2001, the police and the FBI had already arrested and detained, by some estimates, up to three thousand Muslim or Arab noncitizens in the United States. These people were not even suspected of terrorism; they were merely non-U.S. citizens who had allegedly violated some immigration procedure. Many of these people effectively disappeared in U.S. jails; a number were beaten and ultimately deported. It was a real sign of times to come. The Center began a major case, Turkmen v. Ashcroft, that challenged these detentions.

We then started to put together a team of lawyers to represent some of those who might be imprisoned at Guantánamo naval base in Cuba. The first case came quickly. We spoke to a lawyer in Australia, Stephen Kenny, who was representing an Australian citizen who had been imprisoned, David Hicks. He asked us to represent Hicks in the federal habeas corpus suits we were planning, and this became our first case.

The atmosphere in the United States in January 2002 was so fearful and intimidating that we could not get a single other legal organization to join with the Center. We had great difficulty getting local counsel in Washington to help us argue that Hicks’ detention was illegal. And when it became known that I was representing him, I got the worst hate mail I have ever received. I got letters asking me why I didn’t just let the Taliban come to my house and eat my children.

Nevertheless, we finally filed for a writ of habeas corpus in the federal district court in the District of Columbia, on behalf of Hicks and two young men from England, Shafiq Rasul and Asif Iqbal. Subsequently we added Mamdouh Habib, another Australian who had been picked up in Pakistan and shipped to Guantánamo via Egypt, where we believe he was tortured. In the meantime, similar claims were being raised by a private law firm hired by the Kuwaiti government on behalf of a dozen Kuwaiti citizens detained at Guantánamo.

The administration’s principal argument was that no alien held by the United States outside the United States has the right to litigate his detention in a U.S. court. That is, if you are an alien being held at a U.S. base in Guantánamo, Cuba, or Bagram, Afghanistan, or the island of Diego Garcia in the Indian Ocean, you can’t come into an American court, period. Such aliens have no right to habeas corpus and no constitutional rights at all. No First Amendment right to speak; no Fourth Amendment right to be protected against unlawful detention; no Fifth Amendment right against self-incrimination; no right to due process; no right to any kind of a hearing to test their detention.

We thought this argument was very wrong. We believe that any person detained or jailed by the United States has a right to test the legality of his or her detention in a U.S. court. And, even if somehow that broad proposition was not the case, a person detained at Guantánamo certainly has that right. The United States exercises all power in Guantánamo, and the writ of habeas corpus should certainly apply there. Only U.S. courts can protect people’s rights in Guantánamo. No other country’s courts in the world can do so.

Ray: How did the war in Afghanistan lead to the detentions in Guantánamo?

Ratner: What happened when the U.S. military went into Afghanistan in October 2001 was extraordinary. As Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld put it, they “scooped up ten thousand people.” Those were not necessarily people found on the battlefield. Many were from Pakistan and the surrounding areas; many were in civilian clothes; many were taken in midnight raids that had nothing to do with the Taliban or with al Qaeda. And most of them were picked up not by U.S. forces but by the Northern Alliance, a loose coalition in a small corner of Afghanistan whom the Taliban had been fighting to oust.

The Northern Alliance, in conjunction with a bunch of warlords, eventually picked up as many as 35,000 or 40,000 people. The United States was dropping leaflets all over the country offering rewards of anywhere from $50 to $5,000 for members of al Qaeda and high-level Taliban officials. In Afghanistan, these were huge sums of money. Villagers and warlords, including members of the Northern Alliance, started turning over their enemies or anyone they didn’t like, or finally, anyone they could pick up. Among those who have been released are taxi drivers and even a shepherd in his nineties.

We don’t know everything about what happened to the thousands of people who were eventually turned over to or captured by the United States. Initially, many were sent to detention facilities in Bagram and Kandahar, Afghanistan, where the first interrogations took place. A number of detainees reported being beaten at these facilities, and there are reliable reports that techniques amounting to torture were employed. John Walker Lindh, the so-called American Taliban, was strapped naked to a gurney and spent two days in a shipping container.

Some detainees were apparently sent to third countries in a process called “rendition.” U.S. authorities knew that torture would be used by the security services of those countries to obtain information. One of CCR’s clients, for instance, was sent first to Egypt where he was apparently tortured and then sent on to Guantánamo.

Beginning in January 2002, hundreds of these prisoners were transported to Guantánamo. The prisoners included some people picked up outside of the so-called war zone of Afghanistan and Pakistan, in places like Bosnia, Zambia, and Gambia.

Ray: Once they picked up all of these people in Afghanistan and Pakistan, what should they have done with them?

Ratner: Whether you agreed with the administration’s policy or not, a state of war existed between the U.S. government and the Taliban government of Afghanistan, and the United States does have a right to detain combatants in a war, but they have to be treated as prisoners of war under the Geneva Conventions. This prohibits coercive interrogations. And no matter what label was applied to those picked up – POW or not – abuse; cruel, inhuman, and degrading treatment; and, of course, torture are all outlawed. The United States would have had the right to set up a POW camp, and that camp could have been in Guantánamo, but a POW camp is quite different from the lawless interrogation prison that Guantánamo became.

Ray: The Bush administration claimed that none of those picked up were POWs and that the Geneva Conventions had no application to the detainees. Is that claim correct?

Ratner: Absolutely not. The United States was at war with the nation of Afghanistan, which, like the United States, is a country that was and is a signatory to the Geneva Conventions. The Conventions state that they apply to an “armed conflict” between “two or more parties” to the conventions, so there should have been no question of their application to that war.

The Geneva Conventions are quite specific: those captured or detained in a war are protected by the conventions and should be treated as prisoners of war. If there is any doubt as to whether they are POWs, there is a special hearing procedure in which a “competent tribunal” makes an individualized determination as to whether a detained person is a POW. Until that tribunal meets and makes a decision, a detained person must be treated as a POW. The United States, in fact, has a set of regulations that details the procedures before these “competent tribunals,” and the United States has used them thousands of times in prior wars. But the administration refused to do so in this war.

If a hearing finds that a detainee is not a POW, he is then considered a civilian and he is protected by a different part of the conventions. Such a finding might mean that he had no right to take up weapons and kill enemy soldiers – a right given to the members of a country’s military – and he could then be prosecuted for murder. Or the hearing might determine that a person is neither a POW nor a civilian who took up weapons, but was, in fact, taken prisoner by mistake. In that case he should be released. These hearings are crucial, particularly in a war where the United States claims the enemy soldiers did not wear uniforms; mistakes are inevitable in such circumstances and the need for hearings all the more pressing. The key point here is that everyone picked up in a war is protected by the Geneva Conventions. No one is outside the law. No one can be treated arbitrarily at the discretion of his captors.

The End of the Rule of Law

Ray: In May 2004, the press obtained and made public a memo dated January 25, 2002 (592kb PDF), from Counsel to the President Alberto R. Gonzales, to the president, as well as a reply dated January 26, 2002, from Secretary of State Colin Powell (394kb PDF) to Gonzales, regarding the application of the Geneva Conventions. What do these memos say about the law that should be applied to those detained?

Ratner: The Gonzales memo is the beginning of the end of the rule of law with regard to treatment of the Guantánamo prisoners. It openly recommends not applying the Geneva Conventions to the Taliban and al Qaeda.

The memo begins by saying that the president has the constitutional authority to decide not to apply the Geneva Conventions, which is an assumption that I reject. The conventions, ratified by the Senate, are the supreme law of the United States under the Constitution and cannot simply be discarded by the president acting alone.

Gonzales gives three primary reasons for not wanting to apply the conventions. First, a finding that they do not apply “eliminates any argument regarding the need for case-by-case determinations of POW status.” Of course, case-by-case determinations are the very essence of the conventions and are essential to individualized treatment required by law.

Second, the war on terror “renders obsolete Geneva’s strict limitations on questioning of enemy combatants.” In other words, the conventions interfere with interrogation. And third, not applying the Geneva Conventions “substantially reduces the threat of domestic criminal prosecution [of administration officials] under the War Crimes Act (18 U.S.C. 2441).” That statute makes criminal grave breaches of the Geneva Conventions whether or not the detainee is a POW. Grave breaches include, as Gonzales points out, “outrages upon personal dignity” and “inhuman treatment.” As he says, “it is difficult to predict the motives of prosecutors and independent counsel… in the future.”

It seems obvious that, as early as January 2002, the Bush administration was planning on using (or had already used) interrogation techniques that it thought might constitute “inhuman treatment” and violate the conventions, thereby opening itself up to criminal prosecutions. Gonzales concluded that a presidential determination not to apply the conventions “would provide a solid defense to any future prosecutions.”

Powell’s reply memo strongly favors treatment of all detainees under the Geneva Conventions. He says the United States has never determined that the conventions do not apply in armed conflicts with U.S. forces, and that following the conventions would aid U.S. prisoners in being treated as POWs when captured, reduce legal challenges to the detentions, “present a positive international posture,” and “preserve U.S. credibility and moral authority.”

Clearly, Secretary Powell’s advice was not followed; Abu Ghraib says it all.

Ray: Assuming the United States had followed the Geneva Conventions, what should have happened to the POWs?

Ratner: As I said earlier, POWs must be held in a POW camp, not a jail, and the level of restrictions imposed must be determined on an individual basis. POWs have a number of rights: they need only give identifying information (they can give more, but cannot be coerced into doing so), they must be released at the end of the conflict (in this case, the war with Afghanistan), and if they are tried for war crimes, they must be tried by the same system of courts as our own soldiers.

Those who are not found to be POWs can be released if innocent, can be held in secure situations if “engaged in activities hostile to the security of the state,” and can be interrogated and tried for war crimes if appropriate.

Ray: Almost two years ago, there were news reports that it was likely a large number of the prisoners at Guantánamo were not involved in terrorism. What does this say about U.S. policy?

Ratner: It shows that there should have been hearings right away. Even then it was apparent that many of the people in Guantánamo were innocent of any crime. A Los Angeles Times article said that, according to classified material, as many as 10 percent of the Guantánamo prisoners were “taxi drivers, farmers, cobblers, and laborers”; that some were “low-level figures conscripted by the Taliban in the weeks before the collapse of the ruling Afghanistan regime”; and that none of the sixty or so people discussed in the article met the criteria for being sent to Guantánamo.

And I think the 10 percent figure is a gross underestimate. Of the 147 prisoners who had been released two years later, only 13 were then sent to jails. The other 134 were guilty of absolutely nothing. That is already more than 10 percent of all the prisoners. It is certainly conceivable that the majority, perhaps a substantial majority, of the people in Guantánamo had nothing to do with any kind of terrorism.

Ray: In early March 2004, five British citizens were released from Guantánamo after two and a half years and sent to England. When they arrived, one was released immediately, and the other four were held for questioning for a day and then also released unconditionally. What does this tell us?

Ratner: It is truly remarkable. Almost as soon as they hit the soil in England, they were released. Two of those released were my clients, and negotiations were taking place between the Americans and the British from the beginning, two and a half years earlier.

Again, this shows that had the United States obeyed the law to begin with, which is to say given people hearings immediately upon taking them captive – given them any rights at all – these people would have been released immediately. The United States simply kept innocent people in jail in a fashion that is completely outside the law. You can be sure these five Britishers were not guilty of anything at all, or the British would have put them on trial.

And this is not just about the loss of years of these people’s lives, or about whatever brutalities they may have undergone while they were in custody. Think of what it says about everyone else who is still in Guantánamo. The United States has released a few of the many hundreds of people there, but many of the detained prisoners in Guantánamo, like those Britishers, may be innocent of any crime whatsoever.

Rule by Executive Fiat

Ray: President Bush claimed he was applying the Geneva Conventions to the Taliban, but not to al Qaeda. Is this so, and what does it mean?

Ratner: The president did say that in February 2002, but he went on to say that although the conventions applied to the Taliban, they would not be treated as POWs. So they were given no real status under the conventions and no real rights. It was completely illegal.

As to individuals picked up in Afghanistan, Pakistan, and other parts of the world because of an alleged relationship to terrorism or al Qaeda, he did say the conventions did not govern their treatment. On this point, as to those picked up outside the war zone, he may have been technically correct; the Geneva Conventions and the laws of war really apply only to conflicts between states and to civil wars. Al Qaeda and other alleged international terrorists unconnected with the war would not be governed by these rules.

But if the conventions and the laws of war do not apply to alleged terrorists, this does not mean that no law applies to their treatment. Those individuals should have been protected by the set of laws that applies outside of war, a body of law called human rights law, of which criminal law is a branch. Under that set of laws, those detained have a right to an almost immediate hearing before a court, the right to a lawyer, and the right to be charged with a crime. But, of course, the Bush administration did not give anyone the normal rights that apply to those detained outside of war. Yet, while the administration acted as if the “war on terrorism” was a traditional type of war, they would not apply the Geneva Conventions that apply to such war.

Ray: What did this Bush decision mean in practice?

Ratner: Once the president made a decision that no Taliban soldier was in reality protected by the conventions, and that no individual allegedly involved with terrorism or al Qaeda was protected by the conventions or by any other laws, the situation of those detained by the United States around the world became lawless. The treatment of the detainees was left up to the sole discretion of government officials – a lawless situation.

Ray: But isn’t the United States saying that the laws of war apply to those it picked up in Afghanistan, Pakistan, and elsewhere?

Ratner: The president is claiming that the laws of war apply to all those at Guantánamo, all those picked up in the so-called war on terror. But the president is using the laws of war selectively, picking and choosing them as he wants.

There are only two legal systems that apply in dealing with arrests, captures, and detentions: criminal law/ human rights law or the laws of war (sometimes called humanitarian law). But the United States has set up a third system that depends entirely on its own discretion and its own notion of the laws of war.

Ray: Under what legal theory was this done?

Ratner: That’s just it: there is none. This is not authorized by law, not by treaty, and not by customary international law. The laws of war only apply to armed conflicts between two states or to a civil war. When the United States and Germany were at war in World War II, the laws of war applied, and soldiers of one side captured on the battlefield by soldiers of the other side were detained as prisoners of war in prisoner of war camps. And they could be – and were – held in those camps until the war was over. That is where the laws of war apply. This is, of course, what should have been done with the Taliban but was not.

Until now this doctrine has never been applied to conflicts that were not between internationally recognized states or civil wars. It has not been applied to terrorism – not in England, not in Ireland, not in Germany during the Baader-Meinhof attacks. If some fundamentalist or separatist group bombs a building, the persons arrested and charged are not treated under the laws of war; they are treated under criminal law.

But now the United States has said that the laws of war apply to al Qaeda, to al Qaeda supporters, and to virtually anyone they say is an international terrorist. Why? Because, as presidential counselor Gonzales admitted, the administration wants to “use every tool and weapon – including the advantages presented by the laws of war – to win the war.” The laws of war are more flexible than criminal law; if you pick up a soldier, you can simply detain that solder until the end of the war, with no charges, no lawyers, no trial. And if that war is endless, the detentions are endless, or so the administration says.

Ray: How did they justify this use of the laws of war?

Ratner: They justified this in part by arguing that the congressional resolution authorizing the president to use force against those responsible for 9/11 turned the situation into a war. But calling it a war against terrorism, or even authorizing military force to capture alleged terrorists, does not make it a war between nation states or a civil war. It is still an international law enforcement action to which normal criminal law applies.

Ray: Is the administration actually applying the laws of war to those at Guantánamo?

Ratner: In fact, it doesn’t really want to apply the laws of war across the board. It wants to pick and choose, applying the draconian aspects of those laws without granting any of the rights they give to those captured. The United States will not call the people held at Guantánamo prisoners of war, or even prisoners, the official designation being “detained personnel,” or simply detainees. The Pentagon has made up a new term: “enemy combatant.” The entire world is a battlefield, they argue, and all people picked up in that battlefield are enemy combatants because they are fighting against the United States. Therefore, they can be held beyond the end of the war in Afghanistan, beyond the end of the war in Iraq, until the end of the war on terrorism. And that, Secretary Rumsfeld and other officials say, could be fifty years or more down the road.

This is a totalitarian system in which there are no checks and balances on the executive. The president can do whatever he wants, acting as dictator. In this system the courts have no independent function and can’t protect anybody’s rights. The Bush administration has tried to justify this system in the Supreme Court, arguing that it must have full control without “judicial micro-managing.” In essence, the president claims he can order the indefinite detention of noncitizens simply because he says so, and no court can review his decision.

The president has ordered people captured or detained from all over the world – Afghanistan, Pakistan, Africa, the Philippines, Yugoslavia. He has had them put on airplanes and taken them to Guantánamo, a jurisdiction he claims is a law-free zone where prisoners have no right to lawyers and no right to be charged. He detains them as long as he wants and then says that no court can examine what he is doing and that the prisoners have no right to file writs of habeas corpus in U.S. courts.

Then, when it was decided to try some of the prisoners at Guantánamo, while others languished in prison, the president set up a tribunal of his own to try them, with all of its members appointed by him or by the Pentagon and with Rumsfeld et al. having the right to overrule any decisions they don’t like. This is no justice at all.

Ray: Under the traditional rules of war, does one have the right to interrogate prisoners constantly, as the United States admits it is doing in Guantánamo and elsewhere?

Ratner: The Germans did that during World War II. They ran detention centers that were called interrogation camps, not prisoner of war camps. The 1949 Geneva Conventions outlawed interrogation camps and required that such prisoners be treated as POWs. What we have in Guantánamo today is an illegal interrogation camp, an offshore interrogation camp.

The administration simply declares that its prisoners are not prisoners of war, they are enemy combatants, and despite the 1949 conventions, they will not be treated as POWs. There is no legal justification for what the United States is doing, no matter what you call the prisoners. The U.S. inquisitors are not just asking for name, rank, and serial number: they are interrogating people morning, noon, and night. Whether you call it torture; cruel, inhuman, and degrading treatment; or stress and duress, it is a violation of international law.

Ray: Are there other ways the government can deal with those it claims are dangerous suspects? What, in your view, should have happened?

Ratner: The government should have treated 9/11 as a criminal act and not as an act of war. It was not the act of a nation-state; it was the act of a band of criminals or terrorists who wanted to attack the United States. But the Bush administration immediately decided to treat it as an act of war and not simply as an international law enforcement matter. It began to assume war powers, commander-in-chief powers, to override the U.S. Constitution, the court system, Congress, and fundamental aspects of treaties and international human rights law. By labeling it a war, the president had the opportunity to assume huge powers.

Combatants picked up on the battlefield in Afghanistan should have been treated as POWs and held in POW camps, not coercively interrogated, and released at the close of that war. Alleged terrorists should have been treated the way alleged criminals are treated. They are arrested, incarcerated, and given a court hearing, with a lawyer. The court decides whether there is sufficient evidence to hold them in prison and bring them to trial. But the United States has refused to do that.

Ray: As you have said, the administration uses the term enemy combatants to describe those at Guantánamo. What does that term really mean? Where does it come from?

Ratner: In its use of the term enemy combatants and in its discussions sion of the treatment of people under the laws of war, the government bases much of its argument on a famous World War II case called Ex Parte Quirin. The Quirin case concerned German saboteurs who snuck into the United States supposedly to commit acts of sabotage. They were tried before a military tribunal and convicted, some of them were executed immediately; others were released at the end of the war. This case saw the first real use of the term “unlawful combatant.”

But, notwithstanding the similarity of the terms, the Quirin case shouldn’t apply to the Guantánamo prisoners. Quirin involved a declared war between two nation-states, and the defendants were spies or saboteurs working directly for the German enemy. But even those people got a trial – not one whose procedures would be acceptable today, but at least a trial. They were not simply detained forever without any hearing. So the case should not provide any authority for the administration to hold people who are not connected with a nation-state indefinitely without a trial. To the extent some of those in Guantánamo are from the Taliban army, they should be treated as POWs and not as enemy combatants, a legally meaningless term. This is a broad designation the Bush administration is employing to make it appear that those it is detaining in Guantánamo and elsewhere can be held indefinitely and without rights.

Ray: Is there any basis at all for the administration’s claim that it can label those at Guantánamo enemy combatants?

Ratner: The point is that the label does not have any legal significance. Its obvious and only real meaning is the dictionary meaning – a person from another nation who has taken up arms, in this case against the United States. The Bush administration is using this term to refer to alleged terrorists who do not belong to a nation-state and who should be tried under criminal law. Those detainees are not enemy combatants but alleged terrorist suspects.

The administration is using the term enemy combatants for combatants captured in Afghanistan and Iraq who should be classified as prisoners of war. That is what the Geneva Conventions require and that is what the administration is ignoring. Enemy combatant is sort of a catchall term, to which no status or rights apply under international or domestic law and which the administration thus believes it can use to treat people as it wants.

This use of the term has been widely condemned. In 2002, for example, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights of the Organization of American States said that all those at Guantánamo had to have immediate hearings to determine their status. The administration ignored that ruling.

The administration has also used the term enemy combatant to deny the right to a hearing to those at Guantánamo. In a war, the administration claims, one can hold captured soldiers as POWs until the end of the war and no hearings are required. But conventional wars have an end. Here, the administration claims it can hold detainees forever, without the protections that apply to POWs under the Geneva Conventions.

The prisoners in Guantánamo deserve some kind of hearing, rather than indefinite detention. Of course, Rumsfeld says that prisoners can be kept in Guantánamo even after they have been tried by one of the military tribunals. And if they are convicted and serve a sentence, they can still be kept in Guantánamo after that, until he or the president determines they are not a danger to the security of the United States.

Ray: Has there been litigation outside the United States, other than the decision of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights of the Organization of American States?

Ratner: A British court in the Abassi case said that the prisoners at Guantánamo were in a “legal black hole,” that they had no rights under the system the United States was using, and urged the United States – over which the British court conceded it had no jurisdiction – to grant the prisoners hearings.

Ray: Do these decisions have any weight with U.S. courts?

Ratner: Courts can look to these decisions, consider their reasoning, and use it in thinking about their decisions in a case – or at least they should do so.

Ray: Isn’t the administration orchestrating a campaign to try to intimidate federal judges, including the Supreme Court, from citing or considering foreign court decisions such as these, or even foreign opinion?

Ratner:Yes, and a Sense of the House Resolution to this effect has been introduced in the House of Representatives.

Ray: Did the Red Cross give an opinion about the application of the Geneva Conventions to Guantánamo?

Ratner: Yes. The Red Cross rarely goes public, but it did on this issue. Of the Guantánamo detainees picked up in the war zone the Red Cross said, “They were captured in combat [and] we consider them prisoners of war.”

Ray: Shortly after 9/11, the president issued a military order that provided for detentions of noncitizens without trial. What is this order and is that the order under which prisoners of Guantánamo are currently being detained?

Ratner: Initially, it was assumed that most of those captured and detained at Guantánamo were detained under the president’s Military Order No. 1. But in fact, it later turned out that, according to the Bush administration, most were not detained under the Order, but under the president’s powers as commander in chief.

Nonetheless, Military Order No. 1 was a shock. The president, without congressional authority, issued it on November 13, 2001. It was an action taken by President Bush as commander in chief. The order was extraordinary in that it defined people whom the president could detain at will, simply by designating any noncitizen an alleged international terrorist or someone associated with international terrorists, with no legal safeguards and no court orders, nothing but a note from the president to the secretary of defense to detain someone, for as long as the president wants, with no way to appeal such a designation.

The president decided that he was no longer running the country as a civilian president. He issued a military order giving himself the power to run the country as a general. Under the order he claimed the absolute power to arrest noncitizens anywhere in the world, even in the Unites States, and hold them indefinitely and without charges or a lawyer until the so-called war on terror was over, which could be fifty years or forever.

Military Order No. 1 also set up a system of military tribunals to try alleged terrorists, a system heavily slanted toward conviction. Virtually all noncitizens, everywhere in the world, became subject to the whim of the U.S. executive branch if, in the president’s sole discretion, they fit into one of three categories: alleged members of al Qaeda; anyone who harbors alleged members of al Qaeda, whatever “harboring” means; and most frighteningly, anybody alleged to be involved in international terrorism, whatever “involved” means and whatever “international terrorism” means. This is an administration filled with people who considered members of the African National Congress and of most other national liberation movements of the last few decades as international terrorists.

Ray: How can it be that a presidential order allowing for indefinite detention was issued with so little outcry or even public discussion of that concept?

Ratner: As it happened, even though Military Order No. 1 allowed for indefinite detention, it wasn’t seen that way when it came out; it was looked at as an order setting up tribunals. It did outline the basics procedures for those tribunals, which were appalling, and there was some discussion of and opposition to that.

The tribunals were going to be held outside the United States, totally in secret, with military officers as judges. The prosecution was going to be allowed to bring in any kind of evidence, including hearsay evidence. And they allowed the imposition of the death penalty by a majority vote of the judges. So there was initially some protest about the procedures, both within the United States and around the world.

The order contains a draconian detention policy. It says the secretary of defense shall detain such people as the president designates, and that if they are tried, certain procedures will apply. But it does not say they ever actually have to be tried.

Enemy Combatants

Ray: If Military Order No. 1 is not the legal justification for most of the detentions at Guantánamo, under what authority are prisoners being held?

Ratner: The Bush administration claimed, under the president’s constitutional commander-in-chief powers in fighting “the war on terrorism,” unilateral authority to arrest virtually anyone, anywhere, noncitizen or citizen, even in the United States, if he deemed them an enemy combatant. And this was not only the basis for most of the detentions of noncitizens at Guantánamo, but also the president’s claimed basis for the detentions in military brigs in the United States of American citizens Jose Padilla and Yaser Esam Hamdi.

In some ways this is worse than detention under the Military Order; at least under the Order a detainee must arguably fit within one of the three categories referred to above. Under these claimed commander-in-chief powers the president can and presumably does designate people enemy combatants and detain them for whatever reason he wants. When the president’s counsel, Alberto Gonzales, described this sweeping power the president now claims, in a speech to the American Bar Association, he said that the “determination that an individual is an enemy combatant is a quintessentially military judgment” to which the courts, if they inquire at all, must give “great deference.”

In any event, when the administration initially issued Military Order No. 1, it was thinking of enemy combatants as noncitizens. It thought of terrorists as a group as noncitizens and realized there would be less opposition to going after them with this Military Order.

And in either type of detention – whether under the Military Order or the commander-in-chief powers – there are no charges and prisoners have no lawyers, no family visits, no court review, no rights to anything, and no right to release until the mythical end of the “war on terror.” It is truly terrifying. If the Bush administration argument is accepted, it can detain people forever and torture them, and there is nothing any court can do about it.

Ray: In fact, a few of the people swept up in these operations were indeed U.S. citizens. Are there differences between their treatment and the treatment of the noncitizens in Guantánamo?

Ratner: One of the people supposedly picked up on a battlefield in Afghanistan and taken to Guantánamo, Yaser Esam Hamdi, turned out to be a U.S. citizen. So, demonstrating their discrimination against noncitizens, they took Hamdi to a brig in South Carolina, to conditions that might be marginally better than in Guantánamo.

For Hamdi, at least, as a U.S. citizen held in the United States, the courthouse doors were not altogether closed as they were for the noncitizens at Guantánamo. Hamdi could go to court, and the government had to affirm that it picked him up on the battlefield and classified him as an enemy combatant. However, he is still not allowed to have a lawyer to contest his detention, to challenge the hearsay allegations in the government’s affidavit, to call witnesses. He may be an American citizen, but he could still sit forever in a brig in South Carolina, merely on the say-so of some low government official, unless, of course, his position is upheld in the Supreme Court.

Later, another U.S. citizen, Jose Padilla, was also designated as an enemy combatant. His is an even more extreme case of the misuse of military law or the laws of war, detaining someone who should have been brought before a criminal court, if he was to be held at all.

He was not picked up on the battlefield, not even arrested in a foreign country. The FBI arrested him as he got off a plane in Chicago. First, he was held as a material witness, someone whose testimony the government might want for a grand jury. But then the president classified him as an enemy combatant, allegedly because Padilla was investigating the use of a “dirty bomb” somewhere in the United States. Of course, we have no idea if they have any evidence of this, and why, if they do, they didn’t just bring him to trial for it.

But they didn’t indict him and try him. Instead, they swept him from the jail where he was sitting as a material witness, took him to South Carolina, and put him in a Navy brig without any attorney. Imagine, the government merely alleged that a U.S. citizen was involved in some plot and was therefore an enemy combatant who could be locked up forever. As with Hamdi, the government justified his detention solely on the basis of an affidavit, which could not be contested.

After two years, the government allowed Hamdi and Padilla to see attorneys, but only because these cases reached the Supreme Court. Even so, the attorneys were kept in a separate room and their conversations with their clients were videotaped. And the government has not conceded that the attorneys can use any of the information they might have been given to defend their clients. Of course, it was difficult, if not impossible, for the attorneys to discuss the cases with their clients when they finally met; the government was listening.

Ray: What about John Walker Lindh? He wasn’t dealt with as an enemy combatant, was he?

Ratner: No, he wasn’t. John Walker Lindh, a U.S. citizen, the so-called American Taliban, was picked up on the battlefield in Afghanistan, probably by the Northern Alliance, and then turned over to the Americans after being kept in a metal container for two days, strapped to a gurney, naked and blindfolded, in extreme heat. These conditions constitute, in my view, unlawful physical torture.

He was then turned over to the Americans. And because he was an American citizen from a privileged background, and because, I think, they were nervous about what had been done to him, they indicted him, gave him all his rights to counsel, and intended to go forward with a normal criminal trial. In the end he made a deal and pleaded guilty.

Lindh was facing a possible life sentence, or even the death penalty. It is possible that the government threatened that unless he pleaded guilty, it would simply classify him as an enemy combatant, forgo any trial, and hold him indefinitely.

This is apparently what occurred with a group of young men arrested in Buffalo, New York, as alleged conspirators in a “sleeper cell.” They all pleaded guilty because of the threat that they would be charged as enemy combatants and incarcerated indefinitely.

Michael Ratner is President of the Center for Constitutional Rights. He served as co-counsel in Rasul v. Bush, the historic case of Guantánamo detainees before the U.S. Supreme Court.Under Ratner’s leadership, the Center has aggressively challenged the constitutional and international law violations undertaken by the United States post-9/11, including the constitutionality of indefinite detention and the restrictions on civil liberties as defined by the unfolding terms of a permanent war. In the 1990s Ratner acted as a principal counsel in the successful suit to close the camp for HIV-positive Haitian refugees on Guantánamo Bay.

He has written and consulted extensively on Guantánamo, the Patriot Act, military tribunals, and civil liberties in the post-9/11 world. He has also been a lecturer of international human rights litigation at the Yale Law School and the Columbia School of Law, president of the National Lawyers Guild, special Counsel to Haitian President Jean-Bertrand Aristide to assist in the prosecution of human rights crimes, and radio co-host for the civil rights show Law and Disorder.

Ellen Ray is President of the Institute for Media Analysis and the author and editor of numerous books and magazines on U.S. intelligence and international politics. She is co-editor with William Schaap of Bioterror: Manufacturing Wars the American Way and Covert Action: The Root of Terrorism, both published by Ocean Press in 2003.

Guantanamo: What the World Should Know on Narco News:

The Inquisition Strikes Back (Book review by Jules Siegel)Chapter 1: Guantánamo Bay and Rule by Executive Fiat

From the Narcosphere:

The World Knows: Council of Churches Calls for Rights for Guantánamo Inmates

by Benjamin MelançonDoe v. Bush: Suit Filed on Behalf of Guantánamo Prisoners

by Benjamin Melançon“Reaction Forces” beat and humiliated Guantánamo prisoners

by Benjamin MelançonJudge: Guantánamo prisoners can fight for their freedom in court

by Benjamin MelançonWhy the World Must Know: Publisher Margo Baldwin on Guantánamo

by Benjamin MelançonGuantánamo: Detainee torture in US operated prisons

by Andrei Tudor

- The Fund for Authentic Journalism

For more Narco News, click here.