In Querétaro, the Zapatista “Other Campaign” Picks Up the Hammer of the Urban Worker

After Hearing Testimony in Eleven Mexican States, Subcomandante Marcos Sees “A National Uprising” to Come

By Al Giordano

The Other Journalism with the Other Campaign in Querétaro

March 8, 2006

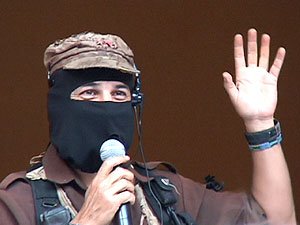

QUERETARO, MEXICO; MARCH 2006: Ever since New Year’s Day, when Zapatista Subcomandante Marcos – in his civilian role as “Delegate Zero” – began his fight-finding mission throughout Mexico, he has heard time and time again the story of “the grand destruction of the Mexican countryside” and found indigenous and farmers alike ready to revolt. But that is only half the story. After eleven weeks of the “Other Campaign” it is clear that the rebellion doesn’t stop at the city line. Here, in Querétaro, the hand that holds the machete sword has found a friend in the hand that holds the worker’s hammer, and Marcos exudes more confidence than ever that this whirlwind tour is setting the stage for “a national uprising.”

Photo: D.R. 2006 Bertha Rodríguez Santos |

As the masked rebel spokesman headed North, he also heard the true stories of teachers struggling to save public education and democratize their union against corrupt bosses, of telephone technicians and marginalized sweatshop factory workers in Puebla and their “story of pain,” of the elderly ex-braceros who assembled in Tlaxcala and will soon join Marcos along the U.S. Border in June… But it was here in Querétaro, birthplace of the Mexican struggle for independence from Spain in 1810, where the hand that holds the machete sickle picked up the worker’s hammer and Marcos said to the urban laborer: “We want to learn from you.”

It is a 21st Century fight that goes way beyond 20th century hammers and sickles: The Zapatista “Other Campaign” has been joined by thousands of organizations, families and individuals; by youths who are tired of being criminalized for being young and rebellious; by housewives “who see the difference between the prices of basic products and the low salaries available” noted Marcos today; by political prisoners and their families; by alternative media and authentic journalists; by gays, lesbians and “other loves;” by children; by elders; by everyone left out by the mercantile and political classes… a breadth of resistance that this country – perhaps no land – has ever seen weaving its many struggles into one big fight.

Perhaps the greatest challenge for a movement that began in the mountains of the Mexican Southeast with a surprise uprising of rural indigenous farmers is whether it can cross over into the factories, the mines and the urban workplaces and become truly national. “The Other Campaign will not be a class struggle,” acknowledged Marcos on Tuesday, “without the workers present.”

The “Other Campaign” reaches out now to the hand that builds and the hand that builds is reaching back. We begin this report in the recaptured Union Hall of the tire factory workers that were fired and replaced when the French multinational corporation Michelin bought the companies – B.F. Goodrich and Uniroyal – where they once labored… and may yet toil again.

“We Will Never Stop Fighting”

Years ago, the former syndicate bosses placed the headquarters of the Union of Uniroyal Workers in the affluent Querétaro neighborhood of Los Alamos: those corrupt administrators of pain sold their rank-and-file members down the drain in 2000. That’s when 638 trained workers were tossed out like trash and replaced by more desperate men and women now working twelve-hour days for 1,000 pesos (about 90 bucks) a week (one third of what the replaced workers once earned).

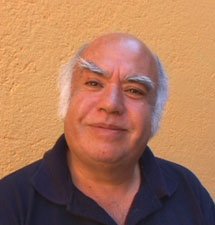

Arnulfo González Nieto Photo: D.R. 2006 Bertha Rodríguez Santos |

“We were sold out by corrupt union bosses, known as Charros,” González Nieto explained. “Charros are part of the corporatism of the Mexican government. They work with the big labor organizations CTM (Federation of Mexican Workers) and CROC (Revolutionary Federation of Workers and Farmers). They’re bureaucrats who become individually wealthy in an illegal manner due to always being at the service of management. The fortune of an individual charro often surpasses that of the factory executive or even its owner. In our case, the CTM signed a contract to protect the interests of the business against any grievances by the workers.”

“We are now unemployed,” continued González Nieto. “Some of us have gone to find better luck and work in the United States. Others drive taxis. Still others find ourselves in a pathetic situation since we are trained to make tires. Last year, one of us, Mario Federico Flores Cárdenas, committed suicide. In his final note, he wrote that it was because he ‘had no more possibilities for earning a living.’ Others have suffered divorces and psychological problems due to not being able to provide for our families, being unable to pay to send our kids to school.”

“When the CTM betrayed us, it took over the Union Hall,” remembered González Nieto. “We fought back. We called an assembly and voted in our officers. In October 2005, we took back this hall and the one in Mexico City. We succeeded in forcing the federal Labor Department to recognize our legal leadership. When we took back these offices, we found them abandoned, looted, our documents were strewn all over the floors. But we have now reactivated the work of the union and this makes us very happy.”

The new workers at the Michelin factories, said González Nieto, “live under terrible surveillance. We can’t have any contact with them. Their salaries are extremely low and they must work twelve hours a day. We’ve received news of injuries and accidents that harmed the under-trained workers. And we’ve learned that this story has happened all over the world.”

Another Mexico… a Global Fight

In 2004, some members of the Uniroyal Union were invited by tire factory workers in France and Italy to visit and tell their stories. “In the French city where 35,000 people worked making Michelin tires in 1985, only 4,000 still have their jobs,” said González Nieto. “We found factories dismantled and being dismantled still. Their jobs went to India and China and Eastern Europe. Yet in 2004, Eduard Michelin, the majority owner of the company, announced an 140-percent increase in profits.”

Workers in Mexico’s factory that makes tires for the Euskadi company learned the lesson of the Uniroyal workers and threw out its charro union bosses, waging a strike that forced the owners to cede control of the factory to the workers and share half the profits with them. “We hear from others across the world that their battle is now an international example,” smiled González Nieto. “They democratized their union and expelled the charros.”

On Tuesday afternoon, Subcomandante Marcos came to this revitalized Union Hall. There, González Nieto told him: “We are from below and to the left and so we have adhered to the Sixth Declaration of the Lacandon Jungle. We and the brothers and sisters of the EZLN are together now. We are the same.”

Other labor organizers – teachers, workers in Mexico’s Social Security Institute (IMSS in its Spanish initials), a representative of workers fighting for their jobs against the Tornel tire company, and others – took the microphone to call for national coordination and action between workers and unions in the Zapatista “Other Campaign.” Then came Marcos’ turn at the mic.

“We want to understand the struggle of the workers in the city, particularly in the industrial sector,” said Marcos. “Our roots and our spinal column are the indigenous people of Chiapas. We don’t come proposing to be the leaders for other sectors. But in this first stage of the Other Campaign we want to know, and make sure others know, of your resistance and to generate solidarity and support.”

Marcos then made proposals to these workers, as he did two weeks ago to the ex-bracero workers in Tlaxcala: “We are asking you as industrial workers… to become teachers in the Other Campaign, to teach us and other sectors what a workers’ movement is… You know how to manage contracts. The indigenous, the youths, the others who don’t yet know you need to know how to do that… Give us classes, please.”

“Some see the Zapatista rebellion, or the fight by Euskadi workers, or your fight, as defects or exceptions of capitalism,” Marcos opined. “But these struggles are really suggestions of the possibility of another Mexico. The Euskadi fight showed us the importance of building international support. The Other Campaign is not only the place of the best damn people in Mexico, but it is also a place for people like you to teach us. Because all the other organized sectors of society are also at the edge of the same abyss.”

“To the proposal that it is time to demand the expropriation of a business, to make this demand specifically… please add the name of the EZLN. In the case of the mine in Coahuila where so many workers just died, the capitalist is responsible,” said Marcos, suggesting that that mine might be the place to begin “to take the offensive” and take back businesses into the hands of the workers. “To say to the workers ‘we’re going for your factory now’ is something new.”

Delegate Zero also proposed that the union members join him in Mexico City on May 1st – International Workers Day – for a mass march, “but that it not just be for one day… We need an Other Worker’s May.” And he proposed “a national gathering” of industrial workers “to be held here in Querétaro, with you as the hosts. And together we can bring together ‘The Other Worker’ in Mexico.”

As the meeting ended, the union leaders and members huddled in a back room with the Zapatista Subcomandante, making plans for the next steps. Men and women who not long ago were thrown out onto the street stepped up onto a national center stage from their reconquered Union Hall. From the ashes of a terrible defeat in this city, just six years ago, after an indefatigable struggle, sprouts the suggestion of an Other Mexico… the expropriation of a nation from those that stole it… a national rebellion… an Other Mexico… not just planted… but also built… by human hands.

Click here for more Narco News coverage of Mexico

Lea Ud. el Artículo en Español

Legga questo articolo in italiano

- The Fund for Authentic Journalism

For more Narco News, click here.