The Narco News Bulletin |

August 15, 2018 | Issue #41 |

narconews.com - Reporting on the Drug War and Democracy from Latin America |

|

BOGOTÁ: Over the last four years, correspondents reporting home to the U.S. and elsewhere from Bogotá have done little but gush about astounding popularity of Colombia's president among the people. For the first time, goes the myth, Colombians see their president working day and night, working tirelessly to make their lives better. Typical is this piece from the Boston Globe published on the eve of the election:

Intense and hard-driving, Colombian President Álvaro Uribe doesn't hesitate to call aides on their cellphones before dawn when a brainstorm hits him or on Sundays when he needs help answering a question at one of his town hall meetings.His passionate, hands-on approach to leadership has helped him drastically improve security and jumpstart economic growth in this war-ravaged nation-and has made him the frontrunner to win reelection tomorrow... But Uribe, the most popular Colombian president in memory, will face daunting expectations in a second four-year term.

...Popular sentiment is certainly with the 53-year-old president. At his final campaign rally in the capital last Friday, the main plaza was awash with banners and supporters urging, "Keep going, President!"

After his easy victory on Sunday, Colombia braces for four more years under Alvaro Uribe this week, the president who has made Colombia an island of subservience to the U.S. while the rest of South America inches slowly toward more sovereign, more popular, and more democratic alternatives. Uribe stays on as the president with one of the smallest real popular mandates in the region. The figure that really led the polls in the 2006 elections, the figure that did not make any headlines in the commercial media but continues to dominate the political scene, is disillusionment with the system.

The Left - once a near non-entity in Colombian politics - showed that it is becoming a major force, finally overshadowing the long-dominant Colombian Liberal Party. This was not a fluke, but the result of years of hard work unifying the various factions on the left and slowly winning back the trust that decades of war and repression had worn away. In 2002, Luis Eduardo Garzón ran as the candidate for a new leftwing coalition called the Independent Democratic Pole (PDI), receiving just six percent of the vote. The next year, however, he won in his campaign for mayor of Bogotá, and PDI mayoral candidates took several other important cities. These were the first real electoral results for the left since the Patriotic Union party was massacred - most major candidates and thousands of party activists assassinated - from the mid-1980s to early 90s. In this year's March congressional elections, "radical" PDI congressman and former M19 guerrilla Gustavo Petro, considered the most popular representative in the lower house, ran for Senate and received the second-highest number of votes of any senator. Now, drug policy reformer Carlos Gaviria has received a truly unprecedented 2.6 million votes, or 22 percent, as the reorganized Alternative Democratic Pole's (PDA's) candidate for the presidency.

Meanwhile, despite supposedly unprecedented enthusiasm for the president and his reelection, relatively few actually cast votes for Uribe. According to the latest figures from Colombia's electoral authorities, turnout was a dismal 43 percent of eligible voters. (Who was "eligible" was also a debatable topic, as many were turned away at the polls for one bureaucratic reason or another, though no hard numbers seem to be available for this.)

Compare this to the 69.2 percent turnout for the presidential recall referendum in Venezuela in 2004. Or the 77.21 percent of eligible Spaniards who voted the Socialist Party into power earlier that same year. Or the 83.6 percent of Italians that recently came out to the polls to narrowly win power for the left in their country as well. Even in the United States and Mexico, two nations noted for their voter apathy, candidates managed to entice more than 60 percent of the electorate in each country to participate in 2004 and 2000, respectively.

The "mandate" for rightist Uribe looks even smaller when compared to presidential elections in other neighboring countries:

Now, all these countries have mandatory voting laws of one kind or another, while Colombia (like Mexico, the U.S., Italy and Spain) has none. But in nearly all these mandatory elections, turnout was still unusually high as voters sensed either the possibility of systemic change for the better, or an attack on a system they wanted to defend. Whatever opinion one has of mandatory voting laws, the leaders of all the countries just mentioned can make a much more credible claim than Uribe that the vote which put them in office really was a majority vote.

So what happened to the masses of Colombians who supposedly have faith for the first time in their government? Who feel protected and safe as ever before? Compared to the 2002 election that won him his first term, Uribe only won 1.3 million more votes this time around - in a country with almost 46 million inhabitants. It may be that someday Colombia has a candidate that inspires folks to get involved again, to believe that voting can make a difference in their lives, but Uribe is not that candidate.

"Here, the people don't vote," Roberto Camacho, one of the millions of people living in the slums and shantytowns around the outskirts of Bogotá, told me in his living room on election day. "The president is only for the rich. The candidates talk of the poor in their campaigns, but once they get into office they forget all about us."

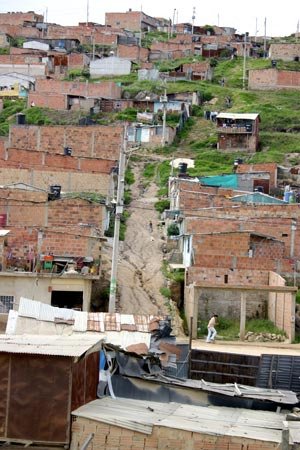

View of homes on hillside in the poor neighbourhood of La Isla, part of Soacha's Comuna 4, south of Bogotá Photos: D.R. 2006 Caleb Harris |

In the last few decades, Colombia has become one of the most urbanized countries in the world. The number of people displaced annually first passed 100,000 in the year 1996, the year that Camacho fled his farm for the city, and hasn't gone back down below that mark since. The worst year of all was 2002, the year of Uribe's first election, when the ranks of the refugees swelled by 413,000, according to the human rights group CODHES. The figure has dropped since then, but still shows no real improvement over pre-Uribe years.

As Sean Donahue reported last year, the mid-nineties began a decade of massacres in Camacho's homeland of Chocó, as powerful economic interests began grabbing up land. When Plan Colombia kicked off in 2000 and an intense campaign of fumigation pushed much of the small-scale coca industry out of the southern departments, the virgin land of the Chocó attracted many of the displaced coca farmers and the brutal U.S.-imposed drug war followed them. Now, Camacho and other Chocoanos in the barrio say, people are beginning to arrive from the jungles of Chocó fleeing fumigations and other manifestations of the drug war as well.

These people displaced by the war join those displaced by poverty, forced to the cities to look for work like their brethren all across Latin America as the economic policies of Uribe and his predecessors make it harder and harder to survive as a small-scale farmer. In the city the displacement often does not end, as paramilitary violence exists there too, combined with the illegal status of the houses they are forced to live in; once arriving to refugee hubs like Bogotá and Medellín, slum-dwellers often still flee from barrio to barrio.

|

In the midst of such marginalization, more and more people see Colombia's "democracy" as irrelevant. What does it matter, asks Camacho, if ten years after the government's war forced him from his land he still can't return without being murdered? No presidential candidate has ever come to Comuna 4 to speak to the people, Camacho says. We walk by a voting station just a few doors down from his house. Indeed, few seem interested; the long lines to vote shown on live TV newscasts from downtown and in middle and upper-class neighborhoods are nowhere to be seen.

Many have said that although voter turnout was low, public opinion polls have shown consistently for the last four years that more than half the country supports Uribe, and thus Sunday's results do reflect popular will. Certainly, an enormous part of the population supports the president. The political violence continues unabated in the countryside, with more individual paramilitary attacks last year than ever, but crime, especially murder and kidnapping, is down in most parts of the country. Several major highways that were once targets for guerrilla and bandit attacks have been lined with soldiers and artillery and are perceived as safe to travel again. Uribe has convinced many that if they give him a "second chance," four more years, he can rid the country of guerrilla insurgencies and drug trafficking once and for all.

But the polls don't tell the whole story. The same marginalization that discourages people from voting keeps their thoughts invisible to pollsters as well. Alfredo Molano, one of Colombia's leading journalists and intellectuals, told Narco News in 2004:

In terms of public opinion polls, he (Uribe) has a very high level of support. But the the opinion polls in Colombia are telephone surveys of a thousand or fifteen hundred people in a few cities - big cities like Bogotá, and medium-sized cities like Villavicencio. But they're all done by telephone. So, in the first place you know there is a large part of the population left out of these surveys. There are seven million telephone lines in Colombia, and, let's say, forty million people. So there is a very large percentage, maybe seventy percent, that does not participate in those polls; they have never been asked, and they will never be asked....There is something else that makes one think that there is a great statistical bias in the polls. When they ask people, they call anonymously. People do not know who is asking them questions. So, you ask someone, do you like Uribe? People are scared, they are not going to say, no, I don't like him, because it could turn out to be a trap. The same thing happens with the army. If, knowing what I know, I get a phone call and they ask me, do you support with army - that is pretty tough, and I'm afraid to answer. These factors are, naturally, never taken into account.

Across the street from that polling station, the words "Bloque Capital" (Capital Bloc of the United Self-Defense Forces of Colombia or AUC, the paramilitary coalition that reached a "peace" deal with the Uribe government) are scrawled on a wall.

One of Uribe's great selling points has been the sweetheart deal he signed with rightwing paramilitary groups, essentially pardoning their crimes (the groups are by far the leading perpetrators of civilian massacres and political assassinations) in exchange for their "turning over their weapons." Camacho in his daily life as a community leader sees the reality behind this charade. While it is true, he says, that violence in has gone down in the neighborhood, the paramilitaries are still there, and still have their guns. "Things are really still the same. They threatened my family, my sons had to leave the barrio or they would be killed. They can't return home now."

Intimidation from the right had been widespread in the lead-up to the election. Four days before the election, a group calling itself "Colombia Free of Communists: Armed Wing of the Former AUC," released a communiqué which read, in part:

Fellow patriots:This is the moment to really choose the present and future of our sacred homeland. We, the Colombia Libre group ("Colombia Free of Communists") are attentive to any step you may take in favor of authentic democracy. The only path that remains for all of us Colombians is to support unconditionally the policy of democratic security of our candidate-President, Doctor Alvaro Uribe Velez.

In no way are we going to permit any other result in the election which draws near, on next Sunday, than the election of President Uribe and his very select group of collaborators. They know very well that they have our complete support. In this respect, we wish to warn you for the last time that: Given the present circumstances in which the country finds itself, we are on an all-out war footing against any interest which is other than the continuity of the Presidential term of our legitimate leader...

We will not permit any other result, and, if it appears on Sunday that the majority are wearing yellow shirts (the color of the leftwing Alternative Democratic Pole), we will dye them another color, the same color that the insurgency and kneeling Liberalism use without any respect: blood red!

Similar letters, threatening violence and proclaiming loyalty to President Uribe, have been sent to specific social groups and organizations. Last month's murder of veteran leftist political activist Hinigio Baquero Mahencha - a survivor of the 1980s violence against the now defunct Patriotic Union party - along with other mysterious recent deaths and disappearances in and around Bogotá have driven such threats home.

"We are very concerned," Alternative Democratic Pole president and senator Samuel Moreno told Narco News the day before the election, "that many people here have shown that they are willing to give up civil liberties in return for peace." This is a good description of the 62 percent of voters who threw their lot in again with Uribe. But what happens when people begin to realize that Uribe cannot deliver peace, only more repression?

The myths that the media have sustained, taking advantage of a war-weary populace eager for good news, cannot last for long. The guerrilla insurgency is too strong, too sophisticated, too battle-hardened to be "defeated" in the military victory Uibe has promised. As a representative of the most conservative sectors of the elite land-owning classes, with a past full of connections to paramilitarism and drug trafficking, Uribe will never be able to negotiate credibly with the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC). The scandals over narco and paramilitary infiltration of the state security forces have been thus far overshadowed by the presidential campaigns, but now that those are over Uribe's disgraced functionaries will begin to hurt his image. The "Free Trade Agreement" (called the TLC in its Spanish initials) Uribe is negotiating with the United States is already widely unpopular, even among the president's poorer supporters. The economic growth he boasts of has yet to make a dent in the level of poverty, and if the recent history of other Latin American countries is any guide, the masses' patience for the neoliberal model will begin to run thin.

During the month of May we have already begun to see what the next four years may hold. Last week we reported on the popular mobilizations around the country against the undemocratic policies of the government, for land reform, against the TLC, and in many areas against the chemical warfare of fumigations that U.S. and Colombian governments wage against their farmlands. (One of the two departments that Gaviria actually carried was Nariño, the country's most heavily fumigated.) Despite the repression the Uribe administration unleashed, treating these unarmed protesters as enemy combatants, social leaders have declared themselves more determined than ever to keep organizing, keep resisting.

During Uribe's time in office, the United States has pumped $3.5 billion in into his government. U.S. officials have given him a free pass on potentially disastrous scandals involving drug corruption and human rights atrocities. Uribe proved that, with this support from Washington, he could repeal the article of the constitution limiting a president to one term and could win that reelection. But with the collapse of Colombia's longstanding two-party system, the national emergence of an electoral left, and the ever-looming possibility that, one day, the majority might turn out to vote, he's going to have his hands full trying to govern in the next term as easily as it came in his first.