Legislators from Six Nations Call for Drug Legalization

Bolivian, Colombian, Mexican, Uruguayan, Costa Rican and European Legislators Offer Prescriptions for Change

By Adam Saytanides

Narco News Authentic Journalism Scholar

March 11, 2003

Organizers of the Out From the Shadows summit in Merida last month were hopeful that the presence of Congressmen and women from seven Latin American nations would give drug policy reform a much-needed boost in legislatures throughout the hemisphere.

There were some disappointments though: Bolivian Congressman and national phenomena Evo Morales was unable to travel due to violent outbreaks in La Paz; Peruvian Congressman Michael Martinez likewise was absent, though he sent a representative in his stead to reassert his support for reform; and Brazilian Congressman Fernando Gabeira’s workload did not allow him to get away – instead, he sent a letter expressing his eagerness to work with his legislative counterparts to affect change throughout the Americas.

But overall, organizers and parliamentarians felt the conference was a huge success. This was the first time drug policy reform advocates that hold government posts were able to unify their efforts, sharing their triumphs and setbacks in their home countries, and brainstorming new strategies for an international campaign against drug prohibition.

All agreed on several main points: 1) that narco-corruption has seeped into the highest levels of government—undermining law enforcement efforts; 2) law enforcement efforts need to be more focused on the international traffickers and dealers, not the campesinos, cocaleros, or drug-using individuals who bear the brunt of an increasingly offensive Drug War; 3) citizens with drug-use problems, like those addicted to heroin and cocaine should not be incarcerated—this method of enforcement is both inhumane, costly, and invades personal privacy; 4) harm-reduction strategies (i.e., needle exchange for IV users to prevent the spread of HIV) should be implemented immediately; 5) some form of decriminalization of illicit drugs will be necessary to reduce the profits being reaped in the Black Market, which has created an overlapping world-wide network of formidable organized crime; 6) the United States government is the main obstacle blocking international drug policy reform.

As these six congressional representatives made the case for drug policy reform in Merida, Narco News was there. In the years and months to come, our reporters will keep close track of their efforts: not only in their home countries of Bolivia, Colombia, Mexico, Uruguay, Costa Rica and Italy, but in the Parliament of Latin America, the Organization of American States, and the United Nations as well.

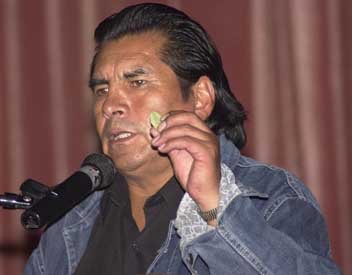

Felipe Quispe, Bolivia

“No one can keep us from planting our sacred leaf— in many places they say ‘coca or death.’”

Felipe Quispe |

Quispe is one of Bolivia’s most influential leaders of indigenous peoples and the vast underclass, which constitute the majority of the population. From 1990-93, Quispe led the Ejercito Guerillero Tupac Katari (EGTK) uprising. In 1993, he was arrested along with other EGTK leaders and activists, and spent five years in jail. Upon his release in 1998 he became Executive Secretary of the United Confederated Syndicate of Farmworkers of Bolivia. This group served as the main voice for Bolivia’s disenfranchised Indian peoples, and diverse opposition groups as well.

Quispe continued to evolve politically, founding the Pachakutik Indigenous Movement in 2002. Pachakutik, which means the dawn of a new day, is a party that fields indigenous candidates to campaign for seats in Bolivia’s Congress. In August, Quispe himself was elected, and now he carries the title of Diputado, or national congressman..

As a congressman, Quispe has continued his militant activism, engineering highway blockades in his native Aymara country. In January 2003 a blockade led to the deaths of 22 campesinos at the hands of Bolivian military forces. Until then, the division between Quispe and Evo Morales had divided the opposition. But the killings in January caused them to join forces at a historic meeting in Cochabamba, where a formal alliance was formed. Now a more unified social movement is sweeping across Bolivia.

Quispe’s much-anticipated speech in Merida had been scheduled for Thursday afternoon. But now the ex-guerilla fighter turned legislator was being called home. Bolivia was in turmoil, and he had a flight to catch in a few hours.

When Quispe reached the podium, he apologized. “I do not speak Spanish very well,” he explained. “It’s an oppressor’s language, and I only learned it when I was 20-years-old.”

“I will talk about coca,” he began, holding up a two-inch, teardrop-shaped green leaf, and inserting it into his mouth—a process he would repeat throughout his talk. “Here is the sacred coca leaf. Our people have used it for thousands of years. We have bled for this crop.”

Quispe gave a brief synopsis of Bolivian history from the indigenous point of view. Until 1952, Bolivia’s Indians were trapped in a feudal system, attached to a single plot of land, and in a state of indentured servitude. “We have had to survive hunger, misery, and oppression with ‘coca en la boca.’” It is the energetic properties of coca that enabled his people to work “from dawn till dusk” in colonial mines. The nutritive value of coca leaves helped workers to carry out the backbreaking labor that was demanded of them by imperial taskmasters throughout the 16th, 17th, 18th, 19th, and early 20th centuries.

Today, it is the coca leaf that gives Bolivia’s poor the ability to drive long distances between remote settlements, and allows young students to study all through the night.

The chewing of coca, which involves placing a pinch of leaf between the cheek and gum, “has become a religion to us,” Quispe said, because Bolivians are so thankful for it’s gifts.

“I’m not talking about the ‘de-naturalized’ uses; the prostitution of the leaf,” he said, referring to the use of powdered cocaine. “If we had the political power, we would find a way to stop the narcotraffickers.”

But the big-time drug-dealers, Quispe complained, are in cahoots with all the major political parties. This he learned while he was serving time amongst narco-traffickers in Bolivia’s prisons. He alleges that the dealers told him that the highest-level ministers of government are all involved in the export of hundreds of tons of cocaine to the United States and Europe. “People in suits never go to jail,” Quispe observed.

In the Aymara nation, he explained, a rite has grown up around the leaf to honor their pantheon of gods. Life’s milestones are likewise celebrated with coca, akin to the importance placed on the kola nut in African cultures. “The U.S. doesn’t want to see this side of the coca,” he said bitterly, as he slipped another leaf between his lips. This form of coca use is not addictive, but still it is illegal to chew or plant coca in Bolivia. In 1998 the Bolivian government enacted “Ley 1008, which sought to regulate coca and the cocaine trade. Ley 1008 had four main pillars: Eradication, Interdiction, Prevention, and Promoting Alternative Crops, like pineapples or bananas. The aggressive eradication of traditional coca farms since 1988 has become the number one topic of discussion throughout Bolivia, and is the main source of social unrest, Quispe claimed.

The growing indigenous political movement has been trying for years to roll back what they see as the most unfair provisions of Ley 1008. Evo Morales, in his role as leader of the Movement Towards Socialism (MAS, in its Spanish acronym) party is preparing to introduce legislation to change Ley 1008. Morales will propose that coca leaf use and cultivation be treated separately from cocaine processing and traffic. Under Morales’ plan, the production and trafficking of controlled substances like cocaine and heroin will still be illegal, but Bolivian campesinos would no longer be subject to penalties for chewing or growing their beloved coca leaf.

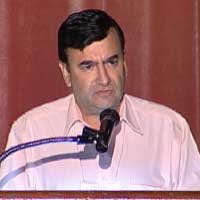

Carlos Gaviria Diaz, Colombia

“I think the only solution is legalization; but I also thinkit will be a long, hard process before we can achieve that.”

Carlos Gaviria Diaz |

“At the end of the day,” he continued in his keynote speech on Feb. 14, “the society we live in is composed of individuals who are free—that goal [of freedom] is not achieved by prohibition.”

Gaviria is worried about an upcoming referendum in Colombia, proposed by the government of President Alvaro Uribe, that may roll back this historic decision by re-instituting penalties for individual drug use. The outcome of this vote is “impossible to predict,” especially because 6 1/2 million votes must be cast for the referendum to be considered binding. But with the current environment of bombings and violence in Bogota, Gaviria said it may be easy for Uribe “to manipulate public opinion.”

In an interview before he left Merida, Gaviria said the summit had been helpful “to find a connection between legislators from different countries that have the same political orientation. Never before have I met face-to-face with congressmen from other Latin American countries—that is why this conference is so important.”

Gregorio Urías Germán, Mexico

“We want every Congress in Latin America and the worldto have this discussion about legalization.”

Gregorio Urías Germán |

Urías is driven to find a way to stop the violence that plagues his home state of Sinaloa, where some of the most powerful drug cartels in the world are based. He said that throughout 20 years of living in Culiacan, a town controlled by narcotraffickers, he had become accustomed to seeing two or three dead bodies in the street in a single day. “Not from using drugs, but from the violence caused by narcotraficantes,” Urías explained. “Mexico is fighting for peace, and struggling with the War on Drugs just like the US is fighting the war on terrorism.”

Urías has become frustrated with what he calls “the repressive policies of the UN and the OAS (Organization of American States),” and follows too closely the foreign policy objectives of the United States. He thinks a different kind of drug policy can be formulated in the Parliament of Latin America, mainly because its members are congressmen, who must answer to voters. The problem in the UN and OAS is that diplomats are all appointed by the executive branches of government, and do not have to answer directly to the people, he says.

“If Latin America starts the debate on legalization, we can start to put pressure on the developed countries,” he said, outlining his diplomatic strategy. “Maybe then, finally, the United States will accept that international organizations have the right to reevaluate these failed policies.”

Margarita Percovich, Uruguay

“I believe in 100% legalization;but in Uruguay, we must go step-by-step.”

Margarita Percovich |

Currently, there is a free needle-exchange program for heroin addicts in Montevideo, and sensitivity training for police who arrest drug users, she says. This is in large part due to the 2000 appointment of Dr. Leonard Costa to head the Junta Nacional de Drogas, Uruguay’s equivalent to the DEA. According to Percovich, Dr. Costa is a liberal who empathizes with the arguments of the legalization movement. Unfortunately, he is powerless to implement changes in enforcement: this falls under the jurisdiction of the police and justice departments. All Dr. Costa can do is to address health issues and try to open a national debate on drug policy, and she thinks he’s doing a great job.

Drug use in itself is not a big problem in Uruguay. “Mostly, it’s marijuana,” Percovich said. “Heroin and cocaine is not a big problem, but it is rising.” Money laundering, allegedly by both Latin American and Arab banks, is the most conspicuous manifestation of narco-trafficking in Uruguay.

The main problem in affecting a change in drug laws, Percovich said, is the fact that Uruguay has repeatedly ratified UN resolutions to address the global regulation of illegal drugs. Once these international treaties are signed, Percovich explained, the Uruguayan legislature goes along. In 1974, the military junta ruling Uruguay decreed that consumers of drugs would not be arrested. Instead, penalties were set for cultivation and distribution. But in practice individual drug users are continually harassed and detained as the police try to root out their suppliers, Percovich said.

In addition, the ruling coalition between President Jorge Batlle’s Partido Colorado and the Catholic, conservative Partido Nacional makes it impossible to pass legislation decriminalizing marijuana, cocaine or heroin use, Percovich explained.

So Percovich prefers to work closely with Dr. Costa to implement as many harm reduction measures as possible. She supports Mexican congressman Urías’ efforts to open up a legalization debate in the Latin American Parliament, but feels it will not have the desired impact. “The Latin American Parliament has no teeth,” she said. “We should go directly to the UN, which can force the Uruguayan government to go along.” Percovich is currently lobbying Uruguay’s foreign minister to change his position on drug enforcement before the upcoming April meeting of the UN Committee on Narcotic Drugs in Vienna.

Ronaldo Alfaro, Costa Rica

“The summit opened my eyes.” Ronaldo Alfaro |

Narco-trafficking is not nearly as big a problem in Costa Rica compared to other parts of Central America (like Mexico or Panama, for example), but Alfaro described issues that sounded strikingly familiar. “We spend hundreds of thousands of dollars each year on the Drug War, with no results,” Alfaro declared, noting that although other nations spend much more, this is a lot of money for Costa Rica to spare. And after years of investing in narcotics interdiction, he insists the nation is in a worse situation overall as a result.

Alfaro pointed out that the power of narco-traffickers, the complicity and corruption of public figures and the use of Costa Rica as a narcotics transport hub are all on the rise, despite ever-increasing interdiction efforts by the government. Costa Rica’s drug policy, he argued, has diverted scarce resources from Social Security programs, and is partly to blame for sluggish economic development. In turn, legions of impoverished youth are easily attracted to the lucrative black market in cocaine.

Alfaro went on to say that drug consumption has increased. “We do have a big use problem in Costa Rica—lots of cocaine, and some crack,” he said. “It’s gotten to the point where cocaine is more popular than marijuana,” he claimed.

Particularly troubling to Alfaro as a Libertarian is when he sees civil rights abused in the pursuit of drug users and smugglers. The use of wiretaps by Costa Rican police is increasing. Furthermore, Alfaro objects to jailing citizens that “commit crimes without victims.”

“It is a distraction from the government’s legitimate goals when it tries to repressively impose an ethical code,” he said. “There are two ways to change people’s lifestyle: to persuade, or to repress.” Alfaro feels that a repressive strategy shows a lack of respect for the populace, and will never succeed.

“We have been kidding ourselves that it could be done this way,” he said. Instead, Alfaro has decided that the best way to control drug use and limit smuggling activity is by persuading the citizenry not to use narcotics through “education, information, and dialogue.”

Like his counterpart, Mexican Congressman Urías, Alfaro is hopeful that the congressmen of Latin America can start a legislative dialogue that will spread to other continents. “Our national debate can be a sounding board for other countries,” Alfaro said. “We need to change the pace.”

But to even open the debate in Costa Rica will be difficult. There is no current discussion, neither in the halls of Congress nor on the street, about alternatives to the Drug War. “Not even whispering,” Alfaro said. “The situation is one of ignorance, looking away—it’s not even commonly understood that HIV-AIDS is related to I.V. drug use.”

Elected officials who would like to introduce alternative policies are afraid to go against the grain, fearing they’d never be re-elected by a public that has yet to consider the idea of needle-exchange, let alone full legalization. So the message Alfaro will try to communicate is “Well, it’s time to talk about it.”

To that end, Alfaro said the Out From the Shadows summit has been immensely helpful. He was unaware that a global movement to change drug policy existed. But coming to Merida this week, he said, “opened my eyes.”

“It gave me a completely new approach. Before, I just had a philosophical idea. Now I am taking home testimony about problems all over the world, especially in Bolivia and Peru, and how strong a role the U.S. plays.”

Marco Cappato, Italy

Globetrotting for Legalization Marco Cappato |

Cappato is working closely with Mario Perduca, of the International Alliance for Legalization. Together they are crafting a precisely-worded document that can be introduced as an amendment to the 1988 UN Convention to Suppress Drug Trafficking, which outlawed all consumption, production, and trafficking of illicit drugs.

After the summit in Merida, he will visit several houses of Congress in Latin America; then Cappato is scheduled to travel to Athens, where he will ask the Greek foreign minister to support drug law reform (Greece currently holds the EU presidency).

Full Disclosure: The author wishes to acknowledge the material assistance, encouragement, and guidance, of The Narco News Bulletin, The Narco News School of Authentic Journalism, publisher Al Giordano and the rest of the faculty, and of the Tides Foundation. Narco News is a co-sponsor and funder of the international drug legalization summit, “OUT FROM THE SHADOWS: Ending Prohibition in the 21st Century,” in Mérida, Yucatán, and is wholly responsible for the School of Authentic Journalism whose philosophy and methodology were employed in the creation of this report. The writing, the opinions expressed, and the conclusions reached, if any, are solely those of the author.Apertura total: El autor desea reconocer la asistencia material, el ánimo y la guía de The Narco News Bulletin, La Escuela de Narco News de Periodismo Auténtico, su Director General Al Giordano y el resto del profesorado, y de la Fundación Tides. Narco News es copatrocinador y financiador del encuentro internacional sobre legalización de las drogas “Saliendo de las sombras: terminando con la prohibición a las drogas en el siglo XXI” en Mérida, Yucatán, y es completamente responsable por la Escuela de Periodismo Auténtico, cuya filosofía y metodología fueron empleadas en la elaboración de esta nota. La escritura, las opiniones expresadas y las conclusiones alcanzadas, si las hay, son de exclusiva responsabilidad del autor

Abertura Total: O autor deseja reconhecer o material de apoio, o propósito e o guia do Boletim Narco News. a Escola de Jornalismo Autêntico, o editor Al Giordano, o restante de professores e a Fundaçáo Tides. Narco News é co-patrocinador e financiador do encontro sobre a legalizaçao das drogas Saindo das Sombras: terminando com a proibiçao das drogas no século XXI em Mérida, Yucatan, e é completamente responsável pela Escola de Jornalismo Autêntico, cuja filosofia e metodologia foram implantadas na elaboraçao desta reportagem. O texto, as opinioes expressadas e as conclusoes alcançadas, se houver, sao de responsabilidade do autor.

- The Fund for Authentic Journalism

For more Narco News, click here.