Johanna Lawrenson: Organizing on the Run

Lawrenson and Partner Abbie Hoffman Ran the Guantlet of US Law Enforcement to Organize for Justice

By Alex Mensing

School of Authentic Journalism, Class of 2013

May 16, 2013

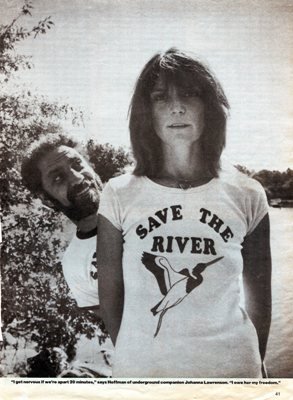

In 1978, Johanna Lawrenson launched a social movement with a fugitive. Her partner, both in life and in the movement, was Abbie Hoffman, an experienced organizer who at the time was wanted by the FBI.

Johanna Lawrenson at the 2013 School of Authentic Journalism in Mexico. DR 2013 Alex Mensing. |

Johanna Lawrenson shared her memories of life on the run with Hoffman during an intereview at the 2013 School of Authentic Journalism, a school founded by organizer and journalist Al Giordano. It brings organizers and communicators together to learn how to advance the efforts of social movements and civil resistance campaigns. Lawrenson has been a faculty member of the last four sessions. In the arc of history, the school represents the realization of a dream that Hoffman and Lawrenson first talked about with Giordano when the three met in the early 1980s.

Living on the run while organizing a social movement takes a particular kind of upbringing and personality. Johanna Lawrenson was raised by Jack Lawrenson, an Irish union leader, and Helen Lawrenson, an author and magazine columnist who knew her way around culture and literature. Jack was an organizer who founded the National Maritime Union of America. Johanna grew up listening to her mother sing resistance songs: “Union Maid, Which Side Are You On?, Solidarity Forever…. Those were my lullabies,” she said.

One of Lawrenson’s first experiences with a community organization happened at age three, riding on her father’s shoulders. “It was the May Day Parade in New York, marching down Broadway with the union,” Lawrenson recalls. She and her little brother even got a taste of the violence that was sometimes associated with union organizing when their mother answered the door and faced down three goons looking for Jack. “The doorbell rang, and by the sound of our mother’s voice we knew something was wrong,” Lawrenson said. The goons broke a window before leaving, but didn’t invade the house.

Jack’s union activities also introduced his daughter to the FBI. Agents visited their home several times during her childhood, her first interactions with a government agency that would later pursue her and Hoffman.

In 1960, a nineteen-year-old Johanna moved to Paris, where she studied at the Alliance Française and worked as a model. Her social life in Paris revolved around her love of the art world, a love she continued to pursue when she moved back to New York in 1968.

In the late 1960s, the FBI drew a distant connection between Lawrenson and someone they were pursuing for destruction of property with a bulldozer. Lawrenson learned later on from a Freedom of Information Act request for her records that she had been on the FBI’s list of top-ten most surveilled people from 1969 to 1972. The FBI visited her friends, family, and even the New York bar where Lawrenson was working. In 1971, she left the FBI’s harrassment behind and moved to Mexico, where she sometimes used an assumed name.

Three years later, Abbie Hoffman fled to Mexico with the FBI on his tail. Hoffman’s successes as an organizer had been a thorn in the side of the US government for years. When the government finally arrested him on drug-related charges in 1973, he skipped bail and crossed the southern border. The following year, Lawrenson met Hoffman—who was using an alias—in Mexico through a mutual friend.

Hoffman was a high-profile figure, and the most powerful government in the world was looking for him. Most people would hesitate before jumping into a relationship with someone under such stressful and perilous conditions. But Johanna Lawrenson felt she had been “groomed for the job.”

Winning Hoffman’s trust was the first step. “He thought it was pretty cool that I was also down there under a false name,” says Lawrenson. She knew what it was like to be the subject of a federal investigation, she knew how to take care of herself, and she shared his commitment to social justice.

Mercedes Osuna — a friend of Lawrenson’s and a long-time organizer and human rights defender in the Mexican state of Chiapas — remembers that when she met Lawrenson she felt as if she had known her all her life. “Johanna is one of those people who have a secure space about them. I trusted her from the start,” Osuna said.

Lawrenson is clear about the role she played in their relationship: “When we were underground, I organized him.” She did most of the driving, she watched people in the restaurants when they ate, and she did the talking while “Johanna’s boyfriend” kept a little distance, his eyes hidden behind a large pair of sunglasses.

Lawrenson recalls their years in Mexico very fondly. “I think we had a charmed life,” she says. “It was one of the best times.” But they had to flee in early 1976 when their cover was jeopardized. They had agreed to be featured in an article by Playboy reporter Ken Kelley, under the condition that he show them the article before publication. He never sent it to them. When Playboy published Kelley’s article, it included information that they felt could lead authorities to their location.

Back in the USA

They went back to the US and spent the warmer months at a cottage that Lawrenson’s great-grandmother had built on the St. Lawrence River in upstate New York. By this time, the individual whom the FBI had linked to Lawrenson years ago had been caught, and the case was closed. But Hoffman was still a fugitive, using various aliases, on the river he was “Barry Freed.” Nevertheless, he took great pleasure in getting to know the local river culture.

And Hoffman missed organizing. In July of 1978, the US Army Corps of Engineers presented them with a challenge that Hoffman could not resist, despite the dangers of becoming more visible. Someone inside the Army Corps of Engineers gave one of their neighbors a series of documents. The Corps wanted to open up the St. Lawrence River for winter-time shipping navigation by breaking the thick ice that froze on the river for several months a year. The plan threatened to create an environmental disaster that would damage local communities along the river.

The first step was to decide whether or not to risk Hoffman’s cover. They both knew this fight would take serious long-term organizing that would involve public appearances by both of them. Despite the risks, Lawrenson and Hoffman decided to push ahead and started organizing.

“How could we not? We lived there,” she says.

They examined the Corps’ proposal that evening, and the very next day they held their first meeting with a couple of friends. One of Lawrenson’s organizing principles is to “get there early.”

They named the organization “Save the River!,” rejecting the longer “Committee to Save the River.” Hoffman knew from his previous organizing experience that a name had to be active. “It was like a greeting,” Lawrenson remembers. “We’re with Save the River!”

As a social movement, “Save the River!” dealt with all sectors of society, from small river communities concerned about their docks to the transportation industry and politicians. I asked Lawrenson about the differences between her approaches to these distinct groups, and she looked surprised: “People are people.”

The movement grew, and Hoffman was able to lead a considerable amount of organizing under the name of Barry Freed without being discovered. But in 1980, he decided to turn himself in and served four months of a one-year sentence.

Free at Last

Lawrenson continued to lead organizing efforts with “Save the River!” working alongside Hoffman, who threw himself back into public with his real identity once he was out of prison. “Save the River!” succeeded in blocking the Corps plan. During the rest of the 1980s, they organized both together and independently, taking on fights ranging from nuclear energy projects to CIA recruitment to US intervention in Central America.

|

Hoffman loved teaching young people, passing along the lessons from his many organizing campaigns. “Teaching was his big thing,” Lawrenson said. “Abbie like teaching because the one thing youth has is impatience. They want it now.”

When Giordano first came into their lives in the early 1980s, he was 21 and organizing with some of the same strategies that Lawrenson and Hoffman had found to be effective. Few others were making use of those tactics, and Hoffman recognized a kindred spirit.

Giordano remembers that when Hoffman learned what Giordano was doing, Hoffman said, “this kid proves my theories.” Lawrenson said she and Hoffman discussed the need for a school that would pass along the spirit, strategy, and tactics that the two of them had learned.

The year Hoffman died, Lawrenson and her friends established the Abbie Hoffman Activist Foundation to carry on his work. In a flyer from the foundation, Lawrenson wrote about the importance of educating new organizers:

“We know that the best memorial to Abbie (and the best thing that could happen to America) would be to train—and unleash—a whole new generation of organizers that would pick up where Abbie left off and mobilize against government oppression and corporate greed everywhere.”

“Abbie would love this school,” Lawrenson said of the School of Authentic Journalism. She and Hoffman had even looked for land on which to build a training center for organizers. As the 2013 session of the school came to a close, she thought of her and Hoffman’s dream. “It just made me want to cry, because this was what Abbie wanted to do.”

Lea Ud. el Artículo en Español

- The Fund for Authentic Journalism

For more Narco News, click here.