Organizer Renny Cushing Tapped the Power of Community to Pull the Plug on Nuke Plants

Clamshell Alliance Drew a Line in the Sand That the Nuclear Energy Industry Has Not Crossed to This Day

By Felicity Clarke

School of Authentic Journalism, Class of 2013

May 14, 2013

Renny Cushing sits back in his chair, crosses his legs and smiles genially as scholars of the Narco News School of Authentic Journalism crawl around on the scorched grass setting up the sound equipment for a video interview with this lifelong community organizer.

Renny Cushing, sporting the No Nukes tee shirt he wore 37 years ago while organizing his town of Seabrook against a nuclear power plant, leading a plenary session at the 2013 School of Authentic Journalism. DR 2013 Rodrigo Jardon. |

School of Authentic Journalism founder and Narco News publisher, Al Giordano is clear on why his friend and community organizing role model, Cushing, is a regular professor at the school.

“People have a hard time understanding what community organizing is and he’s one of the best people to explain it to them. People can learn from his story,” Giordano says.

As one of the key figures in the Clamshell Alliance in the late 1970s and early 1980s, Cushing was effective in organizing a movement that played a major role in freezing the construction of new nuclear power projects in the United States for decades

Through the use of multiple strategies, tactics and activities, most notably the mass occupation of the Seabrook power plant construction site in New Hampshire in April 1977 — in which 1,414 were arrested —and the original (and successful) demonstration on Wall Street in 1979, the anti-nuclear movement assimilated local concerns and nationwide sentiment to effect real change.

The Clamshell Alliance quickly became a national, and even international force, in the anti-nuclear movement. But the network’s origin and central organizing focus was around the small community of Seabrook on the New Hampshire seacoast. It was in 1968 that the proposal for a nuclear power plant in the town of Seabrook was made public. At the time, a rebellious young Cushing was at the local high school making his first forays into political action and organizing. He recalls “trying to challenge the administration in how the high school was run… producing alternative newsletters and leading a demonstration, of all things, against the dress code.” He also took the school board to court for expelling him from school over his sideburns.

Like many young people at the time, the Vietnam War was a major catalyst in his political awakening. “My cousin Ralphy came back with stumps instead of legs,” he recalls. “That gave me reason to pause and think about what our US foreign policy was and what my responsibility was.”

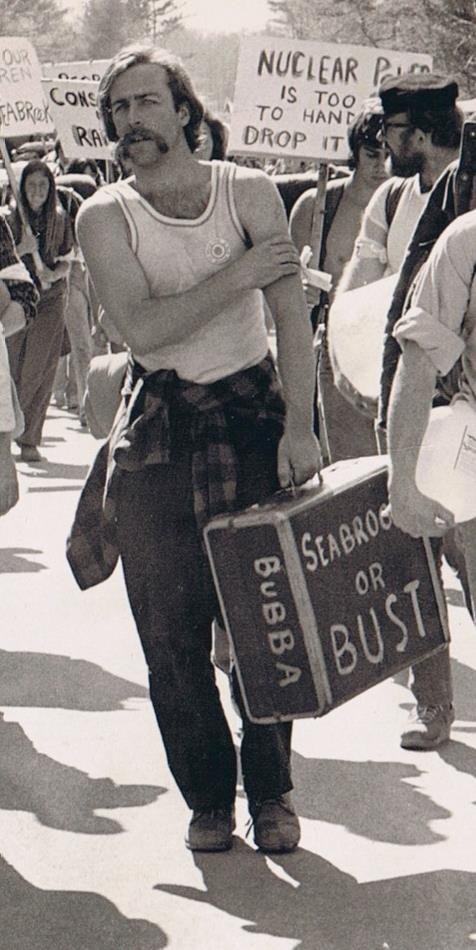

Renny Cushing, at age 24, entering the Seabrook nuclear construction site via the railroad tracks with a group of 18 New Hampshire residents trained to do nonviolent civil disobedience. Photo: D.R. 1976 Lionel DelVingne. |

It was in Mexico that Cushing learned of the death of Chilean Marxist president Salvador Allende on Sept. 11th, 1973. Sitting around a small transistor radio, Cushing recalls that his Mexican companions exclaimed, “Whenever there’s a man that tries to help the poor, they kill him!”

“It was the first time I ever experienced this sense of shame, not just shame but also responsibility,” Cushing adds. “I knew that I lived in the United States. I was from there; I had reason to take on my government. So right after that, I made a conscious decision that I was going to go back to New Hampshire and live the revolution.”

On the Homefront

Back in his hometown in the 1970s, consternation and concern over the proposed nuclear plant was growing. So Cushing resumed his involvement with the Seacoast Anti-Pollution League and also joined the Granite State Alliance — a statewide network of progressive groups — and formed connections with people challenging nuclear projects in the New England region.

As Cushing and fellow organizers educated Seabrook residents on the direct environmental and economic problems that the nuclear plant would bring, and held the first demonstration against the nuclear plant, opposition to the project grew. In the annual town meeting, the townspeople voted against the plant. However despite clear, democratically proven opposition, in July 1976, the US Nuclear Regulatory Commission approved the construction permit for the Seabrook Nuclear Power Plant.

In response to this blatant contravention of the local people’s will, the network of opposition — soon dubbed the Clamshell Alliance, in reference to the New Hampshire seacoast clam flats that were threatened by the hot water exhaust from the plant — organized the first occupation of the Seabrook site in an attempt to nonviolently block construction. On Aug. 1, 1976, 18 people were arrested, including Cushing and his now-wife Kristie Conrad.

In this first occupation, the Alliance consciously limited the action to local people in a move that set and reflected the tone of one the movement’s core groups’ major concerns:

Rooting the movement in the local community and honoring the concerns of the people most directly affected by the project.

Cushing, who lives in a small town in New Hampshire to this day, believes that originating and centering a movement in the affected home territory, around kitchen tables in this case, is the most effective strategy. “I think that’s really the only way that change comes,” he explains.

Collective Action

As an organizer, Cushing stresses the importance of deferring to and respecting local residents: “Honor your local tradition, honor people whose lives are directly affected because ultimately it is those people whose lives are directly affected that are going to become the most effective advocates for your cause.”

The support of local residents was indeed essential for what was possibly the most significant event in Clamshell’s history: The mass occupation by 2,000 people of the Seabrook construction site on April 30 1977. A total of 1,414 people were arrested, one of the largest mass arrests in US history, catapulting the Clamshell Alliance and the anti-nuclear movement into the national and international spotlight.

Recalling the organizing that preceded that historic event, Cushing says: “We were doing something that really had never been done before, so we had to think about what that was… We’d meet regularly, and we were working every day just to gear up to it and do everything you need. We were trying to build an infrastructure. ”

Cushing at the 1977 Seabrook occupation where he was one of 1,414 people to be arrested. |

This attention to detail, considering and planning for every eventuality, is organizing in the truest sense of the word, and was integral to the success of that pivotal moment in the Clamshell movement.

Fighting Goliath

One of the attributes that marks Cushing as an organizer is his ability to communicate the different aspects of a project’s threat, connecting it to the lives of previously unconcerned citizens.

Al Giordano, who came from New York at age 17 to participate in the April 1977 Seabrook occupation and remained closely involved in the movement, highlights this quality, saying: “Renny had a talent for changing the language of the struggle in order to show that this nuke was causing rate hikes and taking food out of your mouths and money out of your hands every month. These were the sorts of emphases that convinced people who weren’t really concerned about the environment or with a nuclear accident because in their own daily lives the pressures to just survive are so great, it’s hard to focus on such ephemeral stuff.”

Following the disregarded Seabrook community vote on the proposed nuclear power plant, the Clamshell Alliance organized town warrants in 20 surrounding towns to vote on whether they supported Seabrook’s right to home rule. In this way, the struggle was translated into an issue of local democracy, galvanizing local communities to stand in solidarity.

These efforts reflect the depth of research that’s involved in creating a dynamic, effective movement, which Cushing identifies as important for breaking down what is often the Goliath force that a social movement fights against.

“We looked at it so it wasn’t just a monolith,” he says, “and tried to see what were the forces [behind the construction of the plant] and see where these forces could be undermined.”

Needed were strategies and tactics that targeted the various governmental and corporate entities supporting the construction of the nuke plant.

“There were many different, simultaneous activities going on at the same time and part of them were in sequence, to be complementary and to build upon something that happened previously,” Cushing says.

Holding sit-ins at banks in the region, following and participating as much as possible in the regulatory process, door-to-door educating of people on the various dangers of nuclear energy, having a clear communication strategy and media committee were some of the diverse activities of the Clamshell movement.

Cushing and his colleagues encouraged people to participate, be it writing a letter to the local newspaper, turning up to vote at the town meeting, attending Clamshell meetings, signing petitions or attending alternative demonstrations.

“There were all these different events leading up to a rally and we tried to design activities that allowed for different things,” Cushing recalls. “When we would have a civil resistance action we would always have in proximity a legal rally, so that people could publicly rally representing people that could not go and engage in civil disobedience. They were there in support and it was also a platform.”

Disarming with Humor

A large part of what inspired people to participate in the collective action against the Seabrook power plant was humor and the sense of fun, and Renny, who’s jovial character shines on first meeting, was a key proponent of employing humor as part of the strategy.

“He’s always had this talent for using loopholes in laws to make his adversary act ridiculous, and in a way that inspires and makes people laugh and not be so afraid of the adversary anymore,” Giordano says. “And it makes the adversary a little more afraid of us. He makes getting arrested fun.”

When the Cushing and Giordano were arrested at the 1979 Wall Street occupation, Cushing identified himself to police as then-New Hampshire Governor Meldrim Thompson (when he didn’t show up for trial, a warrant was issued for the governor’s arrest). Cushing also booked the National Guard Armories, where those arrested in the 1977 occupation were held, to hold a commemorative dance the following year.

“You have to have fun in order for something to be sustainable,” Cushing says, “and in a way, the work is so serious and the underlying issues are so serious that sometimes you need a bit of humor to keep you from being consumed and overwhelmed by the seriousness of the cause in which you’re engaged.”

It’s also an effective weapon, he says: “Humor can really help demythologize your opponent.”

But the essence of community organizing is creating connections and bringing people together. Cushing is a real expert at this, treating everyone he meets with gentle, earnest consideration. In organizing, this attention is vital.

“It really is talking to one person at a time and having other people sharing the conversation, so you begin with a sense of security and how you interact with a person,” he says.

“When you do this kind of work,” Cushing adds, “it relies on an enormous amount of trust. If you’re going to change the world, you have to trust other people to do it with you.”

Giordano, who was inspired to organizing through his experience with the Clamshell Alliance, speaks highly of Cushing’s ability to earn and build trust. “He pays that attention to detail and cultivates his friendships and alliances over long term,” says Giordano. “That’s part of the job of an organizer: making other people understand they’re important to you.”

Following the series of nonviolent activities, occupations and strategic communication, the Clamshell Alliance weakened support for nuclear energy in the financial investment industry and built strong opposition against nuclear energy amongst the population. The Seabrook nuclear plant itself did go ahead, but at half the original size. No other commercial nuclear project has since been completed in the US.

Cushing continues organizing to this day, leading a movement of murder victims’ families against the death penalty following the murder of his father in his home in 1988. He’s also a three-term member of the New Hampshire State House of Representatives.

Speaking in the shade of the Mexico midday sun at the School of Authentic Journalism, Cushing offers this short and simple advice on how to be a successful and effective community organizer: “Be humble. Be committed. Be patient. Be inclusive. Listen well. Be brave.”

Lea Ud. el Artículo en Español

- The Fund for Authentic Journalism

For more Narco News, click here.