John Kerry and Me

Thirty Years Ago, a Young Community Organizer Learned Electoral Politics from the New US Secretary of State

By Al Giordano

Part I of an Occasional Series

January 29, 2013

Author’s note: After various months of researching and writing a book about my earliest adventures in community organizing and media during my teens and early twenties, came the news that one of the people I’ve been writing about, John Kerry, was nominated by President Barack Obama as the next US Secretary of State. Today, the US Senate foreign relations committee confirmed his nomination. I’ve known Kerry through three decades, worked for him twice, covered him as a reporter, argued and fought with him – including many times when he was a guest on my talk radio show – when I thought him wrong and have also had his back when he’s done the right thing. The following text is excerpted and adapted from the still untitled book. My main motive for these writings is to share lessons learned about organizing and media, strategy and tactics, and the experiences that taught those lessons, with the next generations of organizers and journalists. I’d also like to express my profound appreciation to my book editor, Katherine Faydash, for cleaning this chapter up so skillfully and ahead of schedule. – Al Giordano.

In 1971, John Kerry, a soldier recently returned from Vietnam, testified before the US Senate Foreign Relations Committee, denouncing the war and asking “How can you ask a man to be the last man to die in Vietnam? How can you ask a man to be the last man to die from a mistake?” |

Charles F. was the cigar-chomping “political boss” of the town of Greenfield, the capital of Franklin County, where I lived and organized. With his help, I had just spent the autumn spearheading a petition drive to put a referendum on the statewide ballot in November 1982 against nuclear power and low-level nuclear waste dumps. The law would require that before new nuclear plants and waste dumps in the state could be sited, specific environmental safeguards be met. Voters would have to approve new nuclear facilities by referendum. We pitched it as a pro-democracy initiative. The nuclear industry understood perfectly well that it would be the death knell to its future plans.

We had gathered 110,000 voter signatures across the state – a high percentage of them from rural Western Massachusetts—and this had apparently raised eyebrows and interest in Boston. “You are going to work for my friend Kerry,” Charles F. announced. Charles F. was crazy like a fox and prone to provocative declarations, so I didn’t take his statement seriously. My plan was to manage the referendum campaign and then pivot off that victory to close the Yankee Atomic plant in the Berkshire Mountain town of Rowe, which some of my neighbors and I had been organizing to shut down over the previous three years.

I would eventually do both things, but a setback occurred when Boston-area activists with whom I had allied to launch the referendum campaign decided to seize control of the effort, pushing me (and the rest of the Western Massachusetts organizers) aside. We rebels from the western hills had provided the grassroots muscle to get the referendum on the ballot, but anyone who knows Massachusetts politics and activism – and Bostonians’ belief that the sun orbits around them – is familiar with stories like this one. Months later, in June, when the Boston activists’ organization was in financial and organizational shambles, they would plead mea culpa and ask me to come to Boston and run the campaign. I did, and in November we were victorious, having passed the referendum with a winning 1,224,200 votes, to only 602,400 in favor of the nuclear industry.

In the months between all of this, I got to know about the guy named Kerry. Charles F. had told me a lot about Kerry. “He’s a bomb thrower, just like you,” he said, pointing his Dutch Master Panatela into the air. Charles F. told me that Kerry had led Vietnam Veterans Against the War and that his campaign for lieutenant governor was merely a stepping-stone to higher office. “Ever since I saw him in his uniform testifying in the Senate against that damn war,” Charles F., then in his fifties, said, “I knew that young man will be president someday.”

I was skeptical, and my politics were very much to the left and even outside of the electoral world of politicians. Earlier that year I had met the American dissident Abbie Hoffman, who soon after was sent to prison. I had corresponded with Abbie via letters to and from his correctional facility, and when he was released to a halfway house, we began talking on the telephone regularly. I would ask Abbie for advice about my organizing ventures, and he consistently gave me brilliant counsel. When I told Abbie that I was going to meet Kerry – whom he had known in the early 1970s in the movement to end the Vietnam War – he also told me that he thought Kerry might become president someday, and he encouraged me to get to know him.

Charles F. had also been busy telling John Kerry about me: the previous fall Charles F. had driven me throughout Western Massachusetts to countless “town meeting” assemblies, where we conducted a fun and worthwhile dog-and-pony show. I had convinced a bureaucrat in Governor Ed King’s administration to appoint me as an unpaid member of the governor’s commission on low-level nuclear waste. At each town meeting, I would warn the townspeople of the same governor’s plan to site a nuclear waste dump in rural Massachusetts. Then Charles F. would stand up and issue an impassioned call for resistance. We had succeeded in stirring up quite the panic, and 106 municipalities, through their town meeting assemblies, passed local ordinances and zoning bylaws prohibiting nuclear waste dumping within their borders – and people lined up to sign our referendum petition. In many towns more than half the population signed them.

It was during that referendum power struggle, so typical of activist ventures, that I finally met this John Kerry. He came to Greenfield, where Charles F. held a house party for him. When Kerry arrived in Charles F.’s living room, he gave a talk at least partly directed at me. He extolled “citizen activism” and cited the work of the people of Western Massachusetts in organizing against “toxic waste dumps.” (He may not have known we were fighting low-level nuclear dumps, but still, he struck me as a man who respected community organizing in any form.) What made Kerry different from other politicians I had dealt with was his genuine interest in the nuts and bolts of organizing. Others told me, “I’m against nuclear power.” But Kerry talked about the importance of everyday people organizing to save the environment, and he praised our efforts as much for the process of what we were doing as for our goals. I related to that.

After his talk, Charles F. brought Kerry over to me. “This is the young man I’ve been telling you about.” Kerry – a very tall man – put his hands on my shoulders and asked me how we had gathered 110,000 voter signatures. I told him our story and about the town meetings while Charlie jumped in with color commentary. Kerry laughed with us and said he’d like to get me organizing for his campaign. He invited me to Boston the following week to talk about it.

A rival candidate for lieutenant governor, the state legislator Lois Pines, had also tried to hire me, and some people who had supported our anti-nuclear organizing were big supporters of hers. So off I went to Boston, on a two-hour bus ride, for a breakfast meeting with Pines and then a lunch meeting with Kerry.

I remember that day mostly for something else: a front-page story in the morning newspapers that would have impact on my life for years to come. Jaan Karl Laaman, a community organizer turned bomb-planting radical associated with the United Freedom Front, had been accused of shooting a New Jersey state trooper and was now on the FBI’s list of top ten wanted fugitives. Laaman had recently become the boyfriend of one of my best friends, Barbara Curzi, who would quickly disappear with her two daughters, Lucia and Nina – who were like my own children to me – and go underground with Laaman’s revolutionary organization. In the coming years they and their group would bomb army recruiting stations and headquarters of military contractors. For years to come, the FBI would spend considerable resources hassling me and others I knew, thinking errantly that we had contact with the underground band or could somehow lead the FBI to them. My refusal to speak with the feds would cause me various problems in the coming years, but no one knew that in February 1982.

I was not pleased at all with the path that Jaan and Barbara had taken. I understood their anger and frustration with the military-industrial complex, but I also believed very strongly in nonviolent strategy as the more effective path to change society. After all, it was working for our young anti-nuclear movement. Between the shock of the front-page headlines and what I considered Boston-area activists’ betrayal of me and all of Western Massachusetts, I began to realize that “activists” did not have all the answers. I was seeking answers to change the world, but I was still so young and not sufficiently armed with the skills to accomplish something that had never been done: the shutdown of an operating nuclear power plant. I called Abbie and told him of my dilemma, that politicians were trying to hire me, but I didn’t want to sell out or become part of the system.

Abbie responded, “Today’s revolutionary keeps one foot in the system and one foot outside of it.” He encouraged me to take the job with Kerry and use it as a learning experience. (Years later I would offer similar counsel to young rebels in the United States, that one of the best ways to learn the skills of community organizing would be to attend the organizing school known as “Camp Obama.”) “You have to learn how politicians think to be able to push them on the issues,” he said. Abbie told me that as a young man he had worked on Stuart Hughes’s anti-war campaign for US Senate in Massachusetts, and he later applied what he learned to his historic organizing of the youth movement against the Vietnam War. “Political campaigns are like organizing school,” he said. “Just don’t get sucked into the governing part after they’re over, and get back out into the street.”

John Kerry, with John Lennon, while organizing Vietnam Veterans Against the War. |

Kerry’s campaign was much smaller and far less organized than I had expected. He had only four staff members – I was about to become the fifth – operating out of a small office, and there were no volunteers there when I arrived. Cam Kerry was campaign manager, Larry Carpman was press secretary, Bonnie Cronin was office manager and scheduler, and Michael Joseph Whouley was field director. Whouley was an Irish American kid my own age, from the working-class neighborhood of Dorchester, and he had come out of the rough and tumble world of Boston politics – we immediately hit it off. He showed me a map of the state and drew a line around the counties of Worcester, Hampden, Hampshire, Franklin and Berkshire. It was almost half the state’s geography and a quarter of its population. “This is your territory,” said Whouley. “There is going to be a state Democratic convention in May. We need 15 percent of the delegate votes to qualify for the ballot. Your job is to get our people elected as delegates and then convince undecided delegates to vote for John.”

“How many supporters do you have out there?” I asked. Whouley gave me a list of ten names and phone numbers. That was all they had. Then he handed me a huge file with the contact info for local Democratic Party leaders in the 172 municipalities in my “territory.” A good deal of them overlapped with the 106 towns that had passed anti-nuclear zoning ordinances, and I had a box of index cards with the names and phone numbers of people I had met while organizing in those places. But there were also the cities of Worcester, Springfield, Holyoke, Chicopee, Pittsfield and others with Democratic Party machine organizations and few, if any, people I knew.

Further complicating matters was that the seven-candidate contest for lieutenant governor took place in the shadow of the rematch between former governor Michael Dukakis and current governor Ed King, a right-wing Democrat who had big support in cities and whom all my friends and I hated passionately. According to Whouley, to get Kerry on the ballot, we needed to win over delegates who supported both of those men. Having already organized with conservative, rural people in the anti-nuclear movement, winning delegates was a familiar challenge, and I embraced it with gusto. And I knew that Charles F. McCarthy – my friend, Irish American “political boss” and sworn enemy of Ed King – would help me. Charles F. had attended political conventions with many of these people for years already.

The convention delegates would be elected later in February, and I had been on the job for only a couple of weeks. With the polarized Dukakis-King rematch almost none of them had determined which candidate for lieutenant governor he or she would support. Part of my job was to organize “house parties” to which Kerry would come to pitch to delegates and get them to support his candidacy. I spent my days and evenings calling delegates from lists provided by the Democratic State Committee and inviting them to those house parties. Kerry would typically come west for a day or two. I’d hop into his station wagon – he drove himself back then – where he had the first “cell phone” I had ever seen, a big black box between the driver and passenger seats. As he drove, I’d brief him on the names and stories of important party leaders and delegates whom I had researched, told him what I thought they wanted to hear from him based on my own conversations with them, and then dial them up, saying, “John Kerry is here and wants to talk with you,” and put him on the phone with them.

When Kerry wasn’t making delegate phone calls, I used those car rides to drill him about how he organized Vietnam Veterans Against the War. He seemed to like answering my endless questions, and I got the impression that people hadn’t asked him much about his experience as an organizer. I learned during those car rides that, in addition to his anti-war organizing, Kerry had been a pioneer in the environmental movement. He regaled me with stories of helping to organize the first Earth Day in the early 1970s and of other ecological battles. That was what we had in common: he’d once been a young grassroots organizer around environmental matters, too. And now he was applying those organizing experiences to electoral politics while I was drinking up everything I learned about electoral campaigning to apply it to grassroots organizing.

Kerry, with Senator Ted Kennedy, organizing to end the war. |

Once a week I traveled to Boston for campaign meetings. The political consultant Mike Ventresca (who sadly died some years later in a hit-and-run accident) began coming to the meetings, too – he would be the convention manager – and giving me instructions on how to do my work. “Don’t you worry,” I replied brashly. “I’ve got it under control. John will win Western Massachusetts. You need to worry about the rest of the state!”

When I wasn’t at campaign meetings, Charles F. would drive me (I didn’t have a car or driver’s license) to visit party leaders he knew, and we’d often drink with them and try to sell them on supporting Kerry. The political boss of Pittsfield, Remo Del Gallo, owned a bar, and the delegates from his ward, workers at the nearby General Electric factory, were regular customers. Some of them had read about my anti-nuclear organizing in the Berkshire Eagle, and they had loads of fun telling me that nuclear power meant jobs for them. They’d laugh as I tried to change the subject.

Charles F. also introduced me to a member of the Young Democrats, Jim Shaer from Agawam, and a Worcester County guy named Bill Bradley (a great guy who passed away in the first days of 2013), whom he had worked with in Paul Tsongas’s campaigns for US Senate (Tsongas was Charles F.’s favorite politician, and I was Tsongas’s sworn enemy because of his support for nuclear power). In two years’ time Shaer and Bradley would join Kerry’s campaign staff when he ran for US Senate and later would work on his Senate staff. In the Kerry campaign I learned bucketloads of tactics, by trial and error, to sublimate my own public persona – there had been a lot of regional media coverage of my anti-nuclear organizing – for what was, after all, somebody else’s political campaign.

One of the more interesting characters I met during those months was Springfield attorney and businessman Anthony Ravosa, a conservative political gadfly known for, among other antics, flying a small airplane with a pro-war banner over the University of Massachusetts graduation ceremony during the height of the campus’s anti–Vietnam War protests. With Ravosa I played up Kerry’s decorated service in Vietnam and talked a lot about Italian food – he came on board. Ravosa’s office was in a former movie theater on Court Square, across the street from the Springfield Civic Center, where the May convention would be held. At the convention, the theater’s marquee greeted delegates: “The Ravosa Family Welcomes First Lieutenant John Kerry to Springfield.” Ravosa and I made strange bedfellows – he was a conservative, and I was an organizer who had been arrested 21 times for civil disobedience at nuclear facilities – and our alliance raised plenty of eyebrows. But that’s exactly what organizing is meant to accomplish: bringing together people who might otherwise hate each other for their differences to work for a common cause. A decade later, when I had cut my teeth as a cub reporter for Springfield’s Valley Advocate, Ravosa would become one of my fiercest allies in bringing down corrupt district attorney Matty Ryan.

Many of the friends and contacts I’d made working for Kerry would also be helpful in later years in my organizing work and, even later, journalism. Vietnam veteran Mitch Ogulewicz would become Springfield city councilor. The Berkshires environmental activist Chris Hodgkins would become a state legislator and then congressional candidate. Worcester attorney Macey Goldman had grown up knowing Abbie Hoffman, and I would see him years later at Abbie’s funeral at Temple Emmanuel. The state representative from Greenfield, Bill Benson, and his wife, Karen, provided me with a room to live in, and Benson had long let me use his State House office and phone to do anti-nuclear organizing. Not knowing that there was a law that forbade use of state offices for electoral campaigning, I’d go to Benson’s office on Beacon Hill to make delegate calls, until one day an aide to a Republican legislator explained that I couldn’t. During a campaign event, Senator Sam Rotondi, one of Kerry’s rivals, threatened me, saying that I’d broken the law by making those calls and vowing that I would be prosecuted, something that never happened. All in all, I was being baptized by fire into the hardball world of Massachusetts politics, a vipers’ nest of seething rivalries and personal grudges.

When the convention came, parties with endless open bars and free food were held for delegates. Peter Yarrow, of the folk group Peter, Paul and Mary, came to Springfield and played at Kerry’s party (they had become friends during the anti-war movement). Kerry – a political outsider with a rap against him as overly ambitious, which stemmed from his unsuccessful 1972 campaign for Congress – was caught between two conservative Italian American state legislators, Sam Rotondi and Lou Nickinello (Remo Del Gallo’s boys would vote for one of them on the first ballot and another on the second, which was perfectly allowed under convention rules), who had the most support from King’s delegates, and two liberal women, state representative Lois Pines and former Dukakis administration environmental secretary Evelyn Murphy, who enjoyed a lot of support from Dukakis delegates. Kerry had never held elected office (although he’d been appointed assistant district attorney in Middlesex County years prior). Some candidates had even less support than Kerry, though, including the colorful Boston city councilor Freddie Langone.

Despite his disadvantages among party insiders, Kerry had the best name recognition among voters, owing to his high-profile anti-war organizing, his congressional campaign, his work as prosecutor, and his regular appearances as political commentator on Boston television. He led in the polls, but getting him 15 percent of the delegate vote proved difficult. Many “issue activists” got themselves elected delegates to get their issues – from the environment to women’s rights to labor union legislation – into the party platform. These people wanted to know Kerry’s stance on their pet issues. Some of them would say to me, “If he was so against the Vietnam War, why did he go fight in it?” Meanwhile, more conservative Democrats who might have otherwise liked Kerry’s history as war hero held his later anti-war organizing against him. Machine politicians supporting King and Dukakis were more favorable toward the three candidates who were in the state legislature: they could trade votes and favors with them. And Dukakis acolytes tended toward Evelyn Murphy, because, after all, she’d been one of them. But Kerry, an attorney in private practice, had no institutional power at all.

Each candidate was given some minutes to have his or her name put into nomination and then to give a speech to try to persuade delegates. There were still many undecided delegates – after all, who really cared about lieutenant governor, a job with virtually no institutional power? Kerry’s speech narrowly averted disaster. He had brought back from Vietnam an audiotape that had been made during a gunfight on the Mekong Delta. The plan was for those awful sounds of weapons fire to precede his speech, which some saw as a way to underscore his war hero experience. I was in the hall the day before the convention for the rehearsal, and that audiotape served only to make me want to hide under my chair! Sanity prevailed, and the plan to play the tape was ditched at the eleventh hour. But no plan B had been devised, and Kerry was simply introduced by Norfolk County district attorney Bill Delahunt, a Vietnam War veteran who would later serve in Congress.

Evelyn Murphy’s convention operation was run by two brothers, John and Rick Rendon, who had concocted a superior battle plan: their floor managers in each of 40 senate district delegations had headphones and walkie-talkie radios. While Kerry’s campaign was playing up his military experience, the Murphy campaign looked and felt like an actual army! They lowered the house lights, and Murphy’s speech was preceded by an audiovisual light show and short movie about her, not a bland introduction by a politician. She took the stage to the Chariots of Fire soundtrack. Delegates were wowed, and Murphy carried the day.

When the time came to vote for lieutenant governor at the convention, only four candidates qualified on the first ballot: Murphy led in the tally, and a lot of delegates said it was time for a woman to hold statewide office. Murphy was followed by Rotondi, then Nickinello, and then Kerry, who came in fourth, exceeding the required 15 percent by only 14 votes. Half of those votes came from my “territory.” Michael Ventresca – Kerry’s convention manager – ran up to me, jubilant. “When you said that I should leave you alone and that you had it under control I thought you were an arrogant little prick,” he said. “But you did exactly what you said you were going to do.” Operatives in rival campaigns hated me for it, and I basked in their loathing. A lot of people apparently didn’t think that Kerry would get his 15 percent.

Lois Pines came short of her 15 percent by about 20 votes but had a second chance to qualify (there would be multiple rounds of balloting until one candidate received at least 50 percent to gain the endorsement of the party convention, a symbolic gesture but one that could provide momentum and visibility to a candidate). I and some other Kerry supporters went to Macey Goldman, whose Worcester area delegation had a lot of Jewish members. Pines was Jewish, but Goldman had gotten many of those delegates to vote for Kerry on the first ballot. And this would be my first act of hardball Machiavellian politics. A small delegation of Kerry supporters that I helped organize suggested to Goldman that it would be advantageous for Kerry in the September primary to have two women on the ballot instead of just having Evelyn Murphy alone there to soak up that group of voters who wanted a woman in statewide office. Goldman seized on that and then went around to other, mostly Jewish, delegates saying that it would be a shame for the only Jewish candidate to be excluded. In the next round of ballots, more than 20 Kerry delegates, mainly from Worcester County, shifted their votes to Pines, thus getting her onto the ballot.

Murphy’s operative Rick Rendon was livid with me, and I loved it. Michael Whouley said we should form a political consulting firm and offered to put my name first: Giordano & Whouley Associates (I went in other directions, but Whouley’s considerable talents would move him up the ladder to become national field director for Bill Clinton’s presidential campaign in 1992 and for Al Gore’s in 2000). Machine politicians like Remo Del Gallo slapped me on the back and made jokes: “I didn’t think a commie like you had it in you to screw your rival so viciously.” With a wink and a nod I denied knowing what they were talking about, but in political operative circles, my name was suddenly on people’s lips. At the age of 22, I had become a player in Massachusetts politics.

That moment would be remembered 22 years later when Kerry became the Democratic nominee for president. The Boston Globe, in a retrospective on Kerry’s political rise, recalled of the 1982 convention:

Because of his controversial past and recent stint as a commentator on WCVB-TV (Channel 5), Kerry enjoyed wider name recognition than his opponents. But he was not a favorite of the party apparatchiks. During a seven-hour, five-ballot endorsement scrum, Kerry barely qualified for the September ballot by winning 15 percent of the delegate votes.But his floor troops artfully maneuvered delegates to help another candidate, former state legislator Lois Pines, reach that threshold on the second ballot. That meant that Kerry would face a primary field of two activist women, Pines and former state environmental secretary Evelyn Murphy, the convention’s ultimate winner, and two male state legislators, Senator Samuel Rotondi and Representative Louis R. Nickinello.

But back when he was running for lieutenant governor, the Kerry campaign had sunk all its resources into the convention battle, and in the weeks afterward there wasn’t money for staff salaries, not even my fifty-buck paycheck. There were also problems getting the voter signatures needed to qualify for the ballot, and my job became spending days out on Boylston Street collecting them. I have always had an aversion to doing the same thing twice, and I had spent the previous fall collecting voter signatures for the anti-nuclear referendum.

It was around the same time that the Boston-area activists from the anti-nuclear referendum, the ones who had so rudely pushed me aside, got back in touch: they had been convinced by a young political operative to invest all the referendum campaign’s funds in a benefit concert, held outdoors on a day when it had rained. The organization had gone broke in the process. Worse, the same guy was pressuring the group to double down on another rock concert, and they didn’t seem to be able to stand up to him. They asked me to come back and be their campaign manager – and they offered me $250 a week.

I took that job, with a considerable pay raise, and I brought along with me the freelance reporter Leslie Desmond to be hired as press secretary. Leslie had been my “closet girlfriend” for a year already, reporting on the anti–nuclear dump movement for the Berkshire Eagle and other publications, so we had to keep our relationship, which would be considered a conflict of interest by some in her business, a secret. Leslie was five years my senior, with a sharp sense of humor and great street sense. When Charles F. and I would go to Berkshire County town meetings, Leslie would show up, we’d pretend not to know each other, and then she’d report the story for the daily Eagle and various weekly publications. She and Charles F. had taken to calling me “Roto,” after a pro-nuclear serial letter-to-the-editor writer denounced me as “Rodomontador.” None of us knew what that meant, but we later learned that it came from Rodomonte, an arrogant braggart in a seventeenth-century Italian novel. Well, he had me there. We all have weaknesses, and half the trick to life is to market them as strengths. “You’re nothing but a ‘Roto-matador,’” Charles F. liked to tease me, intentionally mispronouncing the word, and “Roto” became Leslie’s pillow name for me. I was happy to be “Roto.”

Although I had left Kerry’s staff, I stayed in contact with the campaign, which after the convention had brought in the Brookline political operative Ron Rosenblith as political director and de facto campaign manager. Over the summer and fall, Rosenblith helped me navigate the state’s media and political waters in my new role as statewide campaign manager for the November ballot referendum.

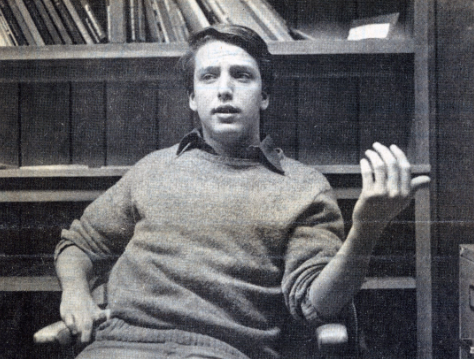

Al Giordano, anti-nuclear organizer, 1981. D.R. 1981 Bob Laramie, The Greenfield Recorder. |

In November, the Dukakis-Kerry ticket was easily elected, and our anti-nuclear referendum had triumphed over a massively expensive industry campaign (another story to be told). With the campaigns over, I met with Rosenblith, who offered me a job starting in January with Kerry’s ongoing political organization. He wanted to teach me political fund-raising and something he called “the donor-activist model.”

But Abbie Hoffman beat him to me – on Christmas Eve Abbie convinced me to cross the Delaware River with him to organize a grassroots campaign against a water-pumping station in Point Pleasant, Pennsylvania. I remained in Bucks County, Pennsylvania, through the spring, where we won a referendum against the Philadelphia Electric Company, the water pump’s main backer – and that, too, is another organizing story for another day.

Next in the series: Kerry’s 1984 US Senate Campaign and a strategy called “theme and message.”

Lea Ud. el Artículo en Español

- The Fund for Authentic Journalism

For more Narco News, click here.