We Have Still Had It Up to Here: The Year a Movement Was Born

Mexico’s Struggle to End the Drug War Is Unlike Any in the World

By Al Giordano

Special to The Narco News Bulletin

March 13, 2012

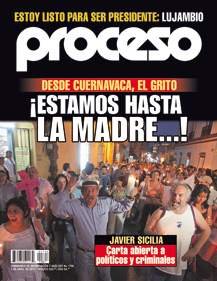

Before the night of March 27, 2011, when a group of young men from Cuernavaca were assassinated, there was no national movement in Mexico to prevent these acts of violence from occurring. Javier Sicilia was a poet, journalist, and editor of an obscure literary journal named Conspiratio, a soft-spoken student of liberation theology and nonviolence, respected within his professions and by the indigenous and other movements he had lifted his pen to support, but not a national public figure nor someone who had ever sought the tribune of a social leader. His country, for more than four years prior, had converted into the epicenter of drug war violence, ever since December of 2006 when a new president, Felipe Calderón, took the reins of the State under a cloud of accusations of electoral fraud. Changing the subject, Calderón immediately ordered the Armed Forces to wage a domestic war, purportedly against narco-traffickers.

|

“I do not wish, in this letter, to speak with you about the virtues of my son, which were immense, nor of those of the other boys that I saw flourish at his side, studying, playing, loving, growing, to serve, like so many other boys, this country that you all have shamed… from these mutilated lives, from the pain that has not name because it is fruit of something that does not belong in nature – the death of a child is always unnatural and that’s why it has no name: I don’t know if it is orphan or widow, but it is simply and painfully nothing – from these, I repeat, mutilated lives, from this suffering, from the indignation that these deaths have provoked, it is simply that we have had it up to here.”

|

When other social movements and organizations with their own grievances toward the Mexican State noticed this new movement’s ability to convoke masses of people into the streets, many began hitching their wagons to it. This turned out to be a double-edged sword. While they increased the ranks of the people marching, they also brought with them the slogans, images and demands of their own, practically a shopping list of injustices never redressed by the State. At this moment, the young cause was in jeopardy of seeing its primary message – to stop the war – overwhelmed or diluted, or, worse, written off by the general public as “more of the same” kind of protest that has long occurred but rarely obtained its desired results.

A father memorializes his murdered son on the columns of the Morelos state government palace. DR 2011 Narco News TV. |

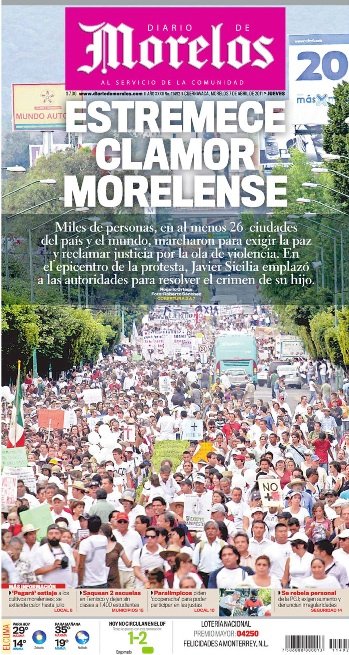

The May march began with a few hundred people walking silently from Cuernavaca and grew to thousands by the time it entered Mexico City (see “Learning to Walk Again with Javier Sicilia,” May 7, 2011, Narco News). Two weeks later Sicilia addressed 80 international journalists and experienced civil resistance leaders from throughout the world at the School of Authentic Journalism, and asked the journalists to accompany the drug war victims on a caravan to Ciudad Juárez, “the epicenter of pain” on the US border in early June.

The silent march that began in Cuernavaca with a few hundred people arrives in Mexico City joined by thousands. DR 2011 Alejandro Meléndez Ortiz. |

As we approach the one year milestone, it is a moment to reflect on the rapid progress of the movement, already the world’s largest popular movement specifically against the drug war and one that has defined the problem for public opinion and also its solution: Stop the war. History books are filled with pages about how new ideas have always met with friction from those accustomed to doing things the old ways, and its no different here. The call for the march to Mexico City brought the first polemic revealing these frictions, because Javier and other victims of the war called for the march to occur in silence. Some activist groups used to marching with specific chants that are typically taught to university students who join protests complained, even accusing the victims of “censorship” or of trying to silence dissent with the use of a resistance tactic of silence. And yet this is exactly what saved the nascent movement from the fate of so many unsuccessful movements before it. The silence, its solemnity, its respect for the dead and disappeared, spoke louder than any chant or rhyme. And it kept the public focus on the war and its victims.

Over the course of this movement’s first year, this fault line would be hit at various points along its trajectory. It has been much like what occurs to rape victims in police stations, courtrooms and the media in every land, in which they are victimized over and over again with accusations that they consented to their rape, that they really “wanted it,” that they dressed in a manner as to invite it, their private lives are called into question, and all this serves to inhibit and intimidate victims from coming forward and speaking of the crimes against them. A similar dynamic has happened to Javier and other victims, which only makes their continued willingness to stand up and speak more admirable and heroic.

The first line of attack against the victims comes from the State and its obedient media organizations: that all those 65,000 killed in the crossfires of the drug war are themselves drug dealers or criminals. But the more hurtful and senseless line of attack comes from what is defined, in military terms, as “friendly fire,” attacks from those who are supposedly on the same side of the struggle. Political parties, for example, are angry with Javier and the victims for not endorsing or lining up behind their candidates, or for meeting and dialoguing with the president or congressional leaders or state prosecutors who are members of different parties. That in those dialogues Javier has kissed or hugged one politician or another (a way that he greeted women and men alike long before the murder of his son thrust the national spotlight on him, and a practice tied to his religious beliefs) has sent columnists and political cartoonists into frenzies of outrage. It used to be that only the false moralists of the right concerned themselves over who kissed whom. Those in the “center-left” who have done the same have not inspired confidence in how they would govern when they get the chance.

Others, still, have promoted rumors and conspiracy theories that Javier or others in the movement are merely jockeying for political candidacies or government jobs (an accusation that is laughable to those of us who have known this reclusive poet and his distaste for bureaucracy and the electoral political system for many years). These kinds of attacks and falsehoods should be seen in the same light as the counterinsurgency efforts of the State: efforts to victimize people who are already victims, simply because they have come out from the shadows and determined to do things their way, not at the bidding of any other political faction except from what words flow from their own hearts.

The “friendly fire” against the victims has also come from non-electoral circles. Some activists, upset that the movement against the war did not adopt their pet causes as its own, or others that come from tendencies that fetishize “revolutionary violence” and are uncomfortable with a concept they don’t understand, that of nonviolence, have likewise disparaged the victims. Paradoxically, the insults that infer that they are politically naïve, or ingenuous, or are being used by the officials they have dialogued with, stem from the victims’ greatest strength: The fact that they are regular everyday people from all classes and walks of life, closer to Mexican public opinion than the “professional activists” and partisan militants have tended to be. Time and time again, this has gone beyond respectful expressions of disagreement.

Add to that the mercenary behavior of many in the media – including in some “alternative media” – to use the movement as a kind of audition for their own individual career moves (if I had a peso for every one of scores of interviews that the ever-accommodating Javier gave freely to a reporter who then called that interview “exclusive,” I’d be able to buy a television network!). The first six months of the movement, in fact, were under a very heavy media glare; the silent march to Mexico City, the bus caravans North and South, the dialogues with the president and congress, but now it is an election year and the commercial media has run off with a different circus. Some look at the comparative lack of media attention and obtain a false reading that the movement has therefore lost steam. But the exit of the media, quite the opposite, has finally given the movement a chance to breathe and begin the more important first steps of organizing itself for the struggle ahead.

Truth is, there was so much media attention in the first months that the movement quickly grew to depend on press coverage to communicate with its own members. The formula was to call a press conference or media event, announce a march or a caravan, and the heavy media attention by itself would bring out the people. That is a very dangerous position for any movement to put itself in, because it puts the communication power of that movement in the hands of other institutions that have their own political and economic agendas. Now that the media is off to the next spectacle, the Movement for Peace with Justice and Dignity has finally been able to begin the ground-up work of organizing its own communications systems, to prepare and train its own ranks – in nonviolence, in attending to the needs of victims, in organizing – that it was not able to do in its early media-driven stages.

What makes this movement so different than previous struggles is that it has brought different kinds of Mexicans that did not previously work together around the same table to develop a language of resistance that is accessible not just to political professionals or activists, but to ordinary people. The victims themselves are as diverse as all of Mexico, and to watch over the past year as people who never did anything public or political emerged as organizers and leaders themselves has been a lesson in civics. People like Maria Herrera, mother of sixteen with four sons disappeared by the violence, who last June appeared at a movement gathering in Morelia, Michoacán, crying in her grief that she did not know how to speak in public, that she never wanted to speak through a microphone, but that her plight has forced her to do it; these are the pillars of this movement. Maria soon evolved from a victim to an organizer and defender of other victims; a bona fide leader. This has happened over and over again and has a multiplying effect as the circle of organized victims widens nationwide.

To the victims have come human rights defenders, clergy and their NGOs, as well as organizations and collectives of youth, students, labor unions, farmers, neighborhood groups, indigenous communities and even middle class citizens (especially poets and other artists who were moved by the murder of the poet’s son) who have drawn the connection between the historic violence against them and the current plague of violence against every Mexican. Many who have worked in solidarity with the Zapatistas of Chiapas for the past 18 years, and who joined their Other Campaign in 2006, have found a path through this movement to continue that work of building a national and organized struggle. The Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN, in its Spanish initials) brought its communities of indigenous who speak the Mayan languages of Tzeltal, Tzotzil, Tojolabal and Chol to converge like tributaries into a gigantic march of tens of thousands in San Cristóbal de Las Casas last May 7, in solidarity with the peace movement’s march to Mexico City. Some observers may scratch their heads wondering how an armed guerrilla organization would find common cause with a peace movement, but those who have observed the Zapatistas for years know that it is an army that has not fired a shot since 1995 and many of its communities have expressly studied and advocated nonviolent resistance as the path to change. The Chiapas community of Acteal, site of a 1997 massacre that shook the conscience of the country, has organized an advanced practice of nonviolence and has eagerly welcomed this younger movement and mentored it during its first steps. A similar dynamic has occurred with the Purépecha indigenous community of Cherán, Michoacán, in the midst of a struggle against illegal loggers and violent crime organizations, and also with Huichol indigenous communities in San Luis Potosí in their struggle against mega-projects by international mining companies that threaten their land and health.

The construction of alliances between such diverse sectors of Mexican society, in fact, disproves the complaints by some that the peace movement is too narrow in its focus. The movement has shown an eagerness to work with any organized sector, support it, and learn from it. The key word there, of course, is “organized.” That’s what brought these sectors immediate credibility and moral authority in this movement, not that they had a shopping list of demands or grievances. The victims desperately seek to learn a successful way to struggle. As Araceli Rodríguez, an important organizer among the victims, told your correspondent when she decided to attend the movement’s first nonviolence training session, “The victims are looking for help and advice from anyone and everyone. We will take all the help we can get.” And anybody and everybody who has approached the Movement for Peace with Justice and Dignity from the position of bringing real aid and support to it has found his and her place within it.

The second year of this movement – Javier and other organizers have often said that ending the war is a struggle that is likely to take years – will bring many of the same challenges and trials as well as new ones. The movement will have to navigate the electoral season through the July 2012 presidential vote, possibly a post-electoral struggle like those of 1988 and 2006 over electoral fraud, and the inauguration of Mexico’s next president in December 2012. The pressures and attacks upon the movement from the political class and their respective house media organs will only increase as the elections approach. Statements made by movement members criticizing or praising anything that any candidate or party says and does will be blown out of proportion by a sensationalist media, and poorly interpreted as some kind of partisanship. Candidates and parties will also make naked attempts to coopt the message of the movement: don’t be surprised to see TV ads that claim a candidate is in favor of “peace,” perhaps even with “justice” and “dignity.” The movement will need to not get distracted by the electoral circus and utilize the cover that the media attention is now on that show to do the more important under-radar work of organizing and strengthening its own capacities for the long haul.

There are also North American organizations that have proposed a “caravan” with Sicilia and other victims in the United States this coming summer. They have their own vices and cultural biases, problems and segregations by race and economic class, that the Mexican movement will have to successfully navigate, and as every Mexican knows, some of our “friends in the North” have opportunistic or colonial tendencies toward Mexico and Mexicans, even if wrapped in the do-gooder language of solidarity. (It was sad, for example, to see that when Javier Sicilia was invited to a national conference of drug war opponents in Los Angeles last autumn, that the man who inspired a bigger national movement toward that goal than any of the North Americans have ever accomplished was not even given his own plenary session; they put almost a dozen people on stage with him, each with a speaking role, thus limiting his own opportunity and time to share his message.) It also remains to be seen if the much larger movement of Mexican and Mexican-American immigrants, one that is organized at the grassroots (and which mobilized, in 2006, the only successful “general strike” in many decades in the US) will be invited by the North American organizations into a meaningful leadership role for any caravan or other actions North of the border. There are also risks ahead in the caravan’s path stemming from the “occupy” protests’ lack of unity over whether to be nonviolent, a dynamic that could even lead to violent incidents discrediting the Mexican movement internationally: it would be a shame and a harm to the Mexican movement if it were swept into those problems out of its sincere recognition of the need to become international.

There are also potential problems with messaging, as some of the North American activists involved in the planning for the possible US caravan are already seeking to diminish the central demand of stopping the drug war underneath a more polarized debate in the US over the issue of gun ownership and sale (as if strengthening one prohibition could possibly untie another). The Mexican movement – whose possible presence in such a caravan in the US would be the caravan’s most attractive reason to exist – will need to take the necessary steps in advance of any such action that its priorities and messages are respected so that events don’t drift away from the nonviolent principles, and that they focus on the victims, and coherence about stopping the war, the strategies that are working in Mexico for a movement define its own path.Yes, it is important to work across international lines and, yes, there are North Americans and organizations worth building a relationship with toward that end. But not all of them are at the table yet – natural allies that are well organized and haven’t even been invited (a frequent consequence of “gringo on gringo crime” of the sort that divides their own efforts for change) – and only a firm insistence by the Mexican movement that they be brought in is going to widen the movement’s North American constituency and ally base sufficiently to bring real change to the violent drug policy imposed by the United States on Mexico.

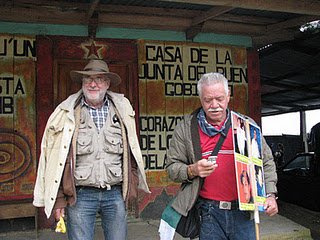

Nepomuceno Moreno (1955-2011), right, with Javier Sicilia at the entrance to the Zapatista Good Government Council building in Oventik during the movement’s southern caravan. DR 2011 Moises Zúniga. |

These are five horrible stories among the many of the 65,000 dead and 16,000 disappeared, and with or without the emergence of the national movement, or their adherence to it, it’s highly probable that the same violence would have happened to them. They were not targeted because of their involvement in the movement, but because of the preexisting struggles they waged which were their motive to find common cause with the movement. The truth is that the movement does not have the power to prevent deaths and disappearances until it succeeds in ending the prohibitionist drug policy that is the cornerstone of the corruption of the State, the impunity of officials and criminals alike, and the institutionalized violence and organized crime that flows from its illicit profits. It is also highly probable that had this movement not begun to organize, others who are now in its ranks would have lost their lives, too, over the past year to the violence. Strength in numbers is not absolute, but it certainly helps diminish the number of these tragedies. In the coming year, the movement and its members may suffer additional losses and casualties. As long as the policy of war continues, tens of thousands of Mexicans will continue to die and be disappeared, their families will suffer, and the movement will have to gird itself not to lose hope or inspiration when the policy it opposes continues to destroy the nation.

Thirty years passed between Gandhi’s return to India and his movement’s achievement of its independence from colonial rule. From Martin Luther King’s organizing of the Montgomery bus boycott in 1955 to the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 there were nine years of intensive nonviolent struggle, also with losses and casualties. Five years passed from the first mass marches in Egypt in 2006 to the 2011 fall of the dictator Mubarak, and our Egyptian friends are still struggling to topple the dictatorship that was behind him. Nonviolent civil resistance is no more an instant recipe than a prolonged guerilla struggle (and both require a high level of training, discipline, organization and strategic creativity to triumph). What nonviolent struggle does have is a significantly higher percentage, over the past hundred years, of achieving the goals that it sets out to win, than other forms of struggle.

In 1810, Mexico won its independence from colonial rule. Its victory was followed by the successful struggles for independence in Venezuela, Colombia, Ecuador, Argentina, Uruguay, Paraguay, Chile, Perú Bolivia and the Central American nations. In 1910, the Mexican Revolution preceded those in Russia and across the world that likewise were waged against economic injustices. In history, of course, no victory is final. True change must be refreshed again and again. It should be no surprise, then, that in 2011 Mexico has appeared, anew, to lead the next century of history and to show the world a path out of the hell of drug policies that corrupt all governments and economic systems and destroy the social fabric of so many nations.

On the afternoon of March 28, on the zócalo of Cuernavaca, the spot where the movement began, it will gather anew and launch another year of struggle. The School of Authentic Journalism, its 80 journalists, communicators and experienced movement organizers and leaders from every continent on earth, will be there to report it far and wide, nationally and internationally. Free speech and a free press are also casualties of this war. Our work as journalists, and our lives, are, too, in the line of fire. Our vocation has its own victims of this war. One of them is the truth. And like every other sector of society, we have our role to play in carefully and intelligently reporting the steps of this movement, documenting its innovations, and tactics, studying, understanding and communicating its strategic dynamics, and assuring that the eyes of the world remain upon it regardless of whether the commercial media does its job or not.

What Javier Sicilia, the victims, and the movement they launched, have accomplished in only one year goes beyond the obvious facts that it is the “biggest” movement against the drug war in human history. It is also the deepest, because it hits at the war’s greatest weapon, that of violence. They have introduced into Mexican public opinion and discourse a new way to fight, different than previous struggles in this country, that of nonviolent civil resistance. As it approaches its second year, the movement is more focused now than before on the work of organizing itself, training its ranks, diversifying and sequencing its tactics, fostering new leaders and organizers. These are the qualities that other historic and successful social movements have had in many lands. But perhaps the greatest joy and inspiration coming from this cause is that it is being accomplished a la Mexicana. Its eventual success in stopping the war here will call checkmate on the United States’ policy of drug prohibition that it has imposed on the rest of América, the world and also against its own people. The policy will fall, worldwide. Thank you, Mexico. And thank you, to the pioneers of this movement. You are defining a century, again.

Click here for more Narco News coverage of Mexico

Lea Ud. el Artículo en Español

- The Fund for Authentic Journalism

For more Narco News, click here.