Mexico’s State of Morelos: "We've Been Trained in the Art of Resistance"

From the Revolution of 1910 to the Civil Resistance of 2011, a Small State Continues to Shake a Nation

By Hanna Nikkanen

Special to The Narco News Bulletin

July 11, 2011

From General Emiliano Zapata to poet Javier Sicilia, something in the Mexican state of Morelos breeds rebellion. After years of social and environmental struggles, the people of Morelos believe they have the blueprint for successful civil mobilization. Will their knowledge change Mexico?

What does golf have to do with civil resistance? Everything, at least in 1995 in the town of Tepoztlán, state of Morelos, south of Mexico City.

“The siege was a time of parties,” María Rosas reminisces. “At three o’clock in the morning, the central square of Tepoztlán was so full of people that it looked like 10 a.m. There were banners, food and newspaper murals everywhere, and everyone had a role to play in the defense of the town.”

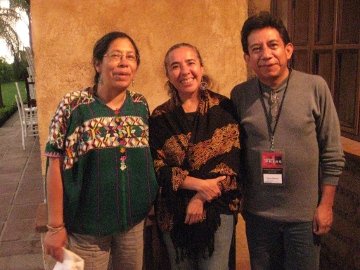

Maria Rosas (middle) at the 2011 School of Authentic Journalism with veteran organizers Mercedes Osuna of Chiapas, Mexico and Oscar Olivera of Cochabamba, Bolivia. DR 2011 Marta Molina |

“Seen from the outside, we were outlaws,” Rosas says. “Seen from the inside, it was the most beautiful thing.”

It was a time between two important eras. The influential former bishop of Cuernavaca, Sergio Méndez Arceo – also known as “the Red Bishop” for his role in bringing liberation theology to the country – had died in Morelos in 1992. In the southern state of Chiapas, the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN, in its Spanish initials) had just launched a campaign that would soon bring in a flood of revolutionaries, journalists and human rights observers from around the world to Mexico.

The movement in Tepoztlán identified closely with the Zapatista insurrection. Even the embroideries in carnival costumes declared solidarity: “We are all TEpoZtLáN,” they spelled out, with the letters EZLN bigger than the others. The inspiration went both ways. Tepoztlán was an autonomous municipality before any were formed in Chiapas.

The link with the emerging Zapatista movement, Rosas remembers, helped Tepoztlán overcome a sense of isolation. For a moment the struggle was about something bigger than a golf course.

“Tepoztlán is made of social networks formed by neighbors, families, coworkers, housewives. During the autonomy they became stronger night by night as we sat in the square and talked about what we had been doing, what we would do next, and how we would get the tamales we needed to survive. It was a form of organization that dates from a time before political parties.”

María Rosas clearly loves these memories of her town’s successful mobilization, but one can’t miss a certain sadness in her voice when she talks about the all-night vigils and the way her little son learned to talk and march at the same time.

Rosas would’ve wished for Tepoztlán to remain autonomous. It didn’t.

After eight months of autonomy, in April 1996, the police killed a local campesino, Marcos Olmedo, near the spot where Emiliano Zapata was shot exactly 76 years earlier. The man’s death was followed by the cancellation of the construction plan. The townspeople, exhausted and mourning but also pleased with their victory, gradually allowed the police and political parties to return to Tepoztlán.

Tepoztlán’s struggle is not the only of its kind. The eviction of the golf course marked a renaissance of resistance movements in the state of Morelos. During the almost 17 years that have passed since Tepoztlán first declared itself a free town, autonomous municipalities have popped up in different parts of the state. They have an impressive track record of winning most of their battles, but those victories have often been, like the one in Tepoztlán, tinged with sadness: many of the movements have failed to bridge the gaping class divisions that characterize Mexican society. Many times autonomy has lasted only a fleeting moment.

Often victory has come with a great cost. Morelos is a state where both the police and organized crime seem to have no qualms about using overwhelming force to maintain the status quo.

That has now become the issue around which Morelos’ inhabitants are mobilizing, hoping that their rebellion will spread outside the state’s borders.

It was in Morelos where poet Javier Sicilia lost his son Juan Francisco to the worsening drug war violence in late March 2011. On May 5th, Sicilia and thousands of others took off from Cuernavaca, Morelos’ capital, on a silent march towards Mexico City.

“All sectors of society have had enough,” says Francesco Taboada, a Cuernavaca-based filmmaker. “That’s the case with the entire country, of course. But Morelos is different. Already before Sicilia we had reached a sense of convergence where different classes learned to fight side by side. Through our experience we’ve been trained in the art of resistance.”

“They’re Against Everything”

Morelos’ northern border touches Mexico City’s urban sprawl. The capital Cuernavaca has traditionally been a weekend playground for the capital’s rich and beautiful.

But that’s not the whole truth about Morelos. A stone’s throw away from the spas and discos of Cuernavaca, the countryside breeds rebellions.

In Anenecuilco, a half-hour drive southeast from Tepoztlán, Emiliano Zapata’s childhood home nowadays hosts a museum. Zapata’s name has been co-opted by nearly every possible political tendency in Mexico, but the fact that the 1910 revolution started in Morelos still has significance to the people of the state.

“Back then all parts of Mexico were facing the same problems,” says Victor Amezcua, a long-time resident of Tepoztlán. In his 60s, Amezcua is an avid student of indigenous models of autonomy. “Land ownership, poverty, slavery – it was not just an issue in Morelos, it was the same everywhere. But the spark that started the revolution came from here.”

This, Amezcua believes, might again be the case in 2011, with the movement inspired by Javier Sicilia’s public mourning. Mexico is fighting a war against its own population. State-sanctioned violence, drug trafficking and impunity affect each Mexican state, but the spark of resistance comes from Morelos.

In conversations about the state’s resistance movements a couple of themes keep coming up: access to water, communal lands, the spillover from Mexico City’s urban growth, and movements that unite poor communities with well-off urbanites. In these conversations, one name is repeated often: Xoxocotla.

“Ah, Xoxocotla,” Francesco Taboada sighs. “They’ve opposed so many things: an airport, a private school, a peanut tax. They’re against pretty much everything, and they’ve won all their battles.”

Roadblocks and Scare Tactics

An hour’s drive south from Francesco Taboada’s home, storm clouds are gathering above Xoxocotla, a town with an impressive reputation for insurgency. It’s hot, as it tends to be here. Armando Soriano is surveying a plot of land that a group of student activists wants to use for planting corn.

Armando Soriano in Xoxocotla. DR 2011 Hanna Nikkanen |

Soriano is a central figure in Xoxocotla. He represents the town in Consejo de Pueblos, an alliance of 13 indigenous Morelos towns that have managed to score victories in a number of battles against the state government. They’ve evicted a landfill that was contaminating the water supply, they’ve stopped real estate developments that threatened to take away communities’ access to fresh water springs, they’ve fought illegal logging in the state’s northern mountains. Many of their victories have been the direct result of Xoxocotla residents’ unusual efficiency when it comes to constructing roadblocks and mobilizing entire communities to defend communal land.

“For example, if we didn’t have access to clean water, the government would first claim that they couldn’t do anything about it,” Soriano says. “We’d block the road and eventually they’d fix the problem. This worked because we had real democracy in this town and we were united in our fight. But in this way we’ve earned the wrath of the government.”

Indeed, Xoxocotla has had to pay a high price for its resistance. In October 2008 Morelos Governor Marco Adame sent the police to dismantle roadblocks that the residents of Xoxocotla had built to show solidarity with a teachers’ strike and to protest against a private condominium development that was sucking its water supply dry. The community quickly outwitted the police and managed to detain a few officers between roadblocks. The federal government responded by sending in the army – something between 500 and 1000 soldiers with an arsenal that included tanks and helicopters.

The military attack lasted all night, even after the residents removed the roadblocks. Xoxocotla was filled with tear gas. There were dozens of illegal home searches, arrests and beatings. It was an absolutely disproportionate response to the situation, and the first taste of president Felipe Calderón’s government’s drive to increase the army’s powers in communities.

“Sending the army to Xoxocotla was a scare tactic that was meant to send a message to all communities that were involved in the resistance,” says Fabiola Sánchez, one of the people behind political magazine El Pregón’s Morelos edition.

“It was a huge shock. There was so much violence, people were beaten and tortured. This had not happened before, so people didn’t even know that tear gas canisters can burn you. Old men and women would grab them with their bare hands and throw them back at the soldiers.”

The attack was followed by weeks of military occupation. It served to increase Xoxocotla’s reputation as a center of insurgency.

However, Armando Soriano is worried about the future of the struggle. The state government is now spending a lot of money in order to divide the community. Residents loyal to the PRI party – in power in Morelos at the moment – receive food, money and even land in exchange for their silence.

“There used to be only two groups here: the people and the government,” Soriano says. “Now we’re divided into six or seven groups. The government did that.”

Bridging the Class Divide, One Protest at a Time

Mexico City is expanding like rings in water. Many of Morelos’ rural communities are seeing the approach of the outernmost circles. The arrival of the middle and upper classes means more trash, more building projects, more pollution, more luxury developments like the golf course that threatened Tepoztlán’s communal lands in the 1990s – and more contact between the traditional communities and the urban population.

This contact has created conflicts, but also unexpected alliances, Francesco Taboada says. The urban middle class and rural communities have found shared interests, especially in environmental struggles. The organizational and tactical skills of the indigenous residents of towns like Xoxocotla have been priceless for these movements, since – as many middle-class participants are eager to admit – city-dwellers here don’t know much about mobilization.

“I first met Javier Sicilia when we were protecting Casino de la Selva,” Taboada says. The movement opposed the construction of a supermarket in a public park on the outskirts of Cuernavaca in 2001 – and lost. A Costco now stands in the spot where the filmmaker once used to go swimming.

Daniel Perera (left) translates Francesco Taboada during his visit to the School of Authentic Journalism. DR 2011 Tyler Stringfellow |

Clinical psychologist Sylvia Marcos was one of the urban professionals involved in the Casino de la Selva movement. Like Taboada, she’s now working alongside Javier Sicilia to demand an end to the drug war violence.

“The Casino de la Selva movement was full of people like me,” Marcos says. “It has always bothered me how these groups tend make indigenous campesino movements completely invisible. The truth is that they have always been at the heart of Morelos’ resistance.”

Taboada finds a short film he made in 2004 about a movement that opposed the building of a road across the river Barranca de los Sauces in Cuernavaca. At that point, three years had passed since the unsuccessful fight for Casino de la Selva. Cuernavaca’s environmentalists had used that time to construct relationships with rural communities and urban workers’ movements, with visible results.

On the video, a wealthy resident of a high-end neighborhood joins electricians and campesinos in a human chain that blocks the building site. Even subcomandante Marcos of the EZLN pays a visit.

“The government doesn’t protect us,” the neatly dressed woman says to the camera, an unexpected presence in an iconic scene full of sombreros, machetes and banners. “The police don’t protect us. We have to protect ourselves.”

The road was never constructed and Barranca de los Sauces remains untouched. That was the first of several victories that the environmental movement has reached in Cuernavaca, Taboada says. It wouldn’t have happened without the organizational skills of the rural communities that joined the fight.

The Shock Doctrine that Got Out of the President’s Hands

A hailstorm hammers the road between Xoxocotla and Cuernavaca. Dulce Jacobo, 18, sits in the back row of a bus and talks about drug war violence. Like Fabiola Sanchéz, she writes about political issues and citizen mobilizations for El Pregón. She has been visiting Armando Soriano in Xoxocotla to talk about the field that her fellow student activists want to use for learning to plant corn.

The soft-spoken teenager looks younger than her years, but her words are mature.

“In the cities of Mexico, people have had this completely unfounded trust in the army and the police. That has changed now. There’s a feeling that any one of us could be the next victim. It’s become a struggle for survival.”

If environmental issues were the umbrella under which different sectors of society in Morelos tentatively approached each other in the previous decade, urban violence seems to be the theme that might now cement those alliances.

In Cuernavaca, where Jacobo studies food chemistry, the increase in violence has been particularly dramatic. The press doesn’t even bother to report all murders committed by the police and drug cartels – the “collateral damage” from the drug war. The violence that used to take place in poor neighborhoods has now spread everywhere.

Jacobo doesn’t seem particularly scared. She says that a combination of religion and political activism has vaccinated her against fear. And fear, she says, has been the basis of president Felipe Calderón’s policies.

Lately, Jacobo reflects, the president has been losing control of this tactic.

“A short while ago people wouldn’t have gone to the streets to protest the violence, they were either too scared or apathetic. Now that a lot of people have already started making noise, the others are finding their courage, too. They feel like there’s security in the masses.”

Ricardo Del Conde, a young filmmaker living near Tepoztlán, admits to belonging to the class that bought Calderón’s shock doctrine. For him, the emergence of an intellectual like Sicilia has finally opened a space of political participation where he feels comfortable.

Javier Sicilia at the 2011 School of Authentic Journalism. DR 2011 Noah Friedman-Rudovsky |

In Tepoztlán, local trader Ruben Flores agrees with Jacobo and Del Conde about Calderón’s motivations.

“The president wanted to militarize the country to make sure his party wins the next election on a platform based on security, but it got out of his hands. Now everyone’s just as scared of the police as they are of the drug gangs. We’re between a rock and a hard place. Things don’t look good for Calderón’s group in the 2012 elections.”

As a man with close connections to the rich and the poor – “I have this verbal diarrhea,” he explains, “I have to talk with everyone.” – Flores has been following the local responses to Javier Sicilia’s movement with interest.

“I was just talking to a group of gas sellers about Sicilia and managed to convince them to join the movement. They’ve been quite skeptical before. To be honest, many of them thought at first that he was just trying to sell his books.”

This is a tough audience for Sicilia’s movement: the urban poor, stuck somewhere between the resistance-prone rural indigenous communities like Xoxocotla and the middle class that Sicilia himself represents. Yet it’s precisely this sector of society that suffers from violence the most.

“One of the gas sellers pointed out that if his child got killed like Sicilia’s, there’s no way he could do what Sicilia does now. No one would care. And it’s true. Every poor person knows that. But it doesn’t mean that they’re not standing by Sicilia’s side.”

“People Who Have Struggled Think Differently”

María Rosas remembers Tepoztlán’s autonomy as a time that was both exhausting and exciting. It was a time when the sound of church bells brought every person in town, no matter how busy or tired, out to the streets to defend the town against attackers.

In the end the exhaustion was greater than the excitement. The people had not thought of autonomy as a goal in itself, but merely as a tactic in the struggle to stop the construction of the golf course.

“While we were struggling we showed solidarity to every possible movement. Afterwards, we started turning inward. Some of us remained active, and we’re now present in Javier Sicilia’s movement, but the town doesn’t do that sort of thing as a community anymore.”

Dulce Jacobo was still in her diapers when the church bells of Tepoztlán were calling for townspeople to protect their autonomy. This year it’s been her turn to live through excitement and exhaustion. She considers herself more radical than Javier Sicilia, but nevertheless joined his march in early May.

“It’s been impressive, especially the possibility to talk to compañeros from different parts of the country. In Topilejo I met people from Acteal, Chihuahua, Mexico City and Monterrey. There were parents whose children had died in Guardería ABC (a day care center in Sonora where 49 children died in a fire in 2009, the tragedy was found to have been caused by criminal negligence) and parents whose children have been kidnapped.”

María Rosas shares Jacobo’s experience. Even though Javier Sicilia is an intellectual and represents Mexico’s small middle class, Rosas believes that the support base for his movement is more popular.

“On Mexico City’s Zócalo, during the hours before Sicilia got there, we heard stories from people who said that their children had gone off to look for work and hadn’t been heard of since. They don’t know if their children are among the unidentified bodies found in mass graves. These are not rich people. They are people with very few resources.”

Dulce Jacobo believes that things will get more difficult from now on. She can’t imagine Felipe Calderón’s government giving in to the movement’s demands, nor does she believe that drug trafficking groups are likely to relent. Another young man has just been killed on the streets of Cuernavaca.

“The important thing is that I don’t feel so isolated now that I’ve met these people. People who have participated in struggles have a different way of thinking, and the campaign gives them a chance to share that with others,” she said during a May interview. “The march to Ciudad Juarez in June will be incredibly important because of that.”

Something to Learn from the Narcos

In Xoxocotla the support for Sicilia is strong, Armando Soriano says. If Sicilia’s movement so wishes, the town is ready to support it doing what it does best: erecting roadblocks, outwitting the police.

He does have one serious worry, though.

“What if they kill Sicilia? You have to remember that when they killed Emiliano Zapata, it was the end of Zapatismo. When they killed Ruben Jaramillo, it was the end of Jaramillismo.”

The storm is almost above us. We’ve returned to Soriano’s house from the field, greeted by dogs and a little granddaughter who introduces herself as Jimena.

“We have a culture of caudillos, strong leaders, and if the leader gets killed then the movement always dies,” Armando Soriano says.

“We really need to look at different alternatives, some wider way of organizing. We need a system where, if one person falls, someone else takes their place. After all, that’s how the drug cartels survive.”

Lea Ud. el Artículo en Español

- The Fund for Authentic Journalism

For more Narco News, click here.