Seeking Justice in the Snake-Pit of Mexican Politics

Oaxacans and Others Fight to Free Political Prisoners

By Nancy Davies

Commentary from Oaxaca

March 19, 2008

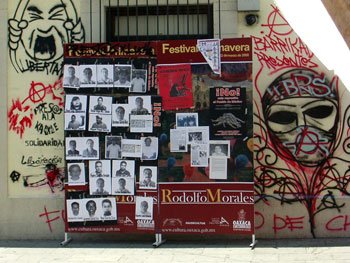

The justice system of Mexico has no category called “political prisoners.” The public knows men and women have been unlawfully grabbed, tortures, raped and/or jailed, as deterrents to social movements. The human rights organizations protest. Posters appear on the walls. Nothing happens. Nobody knows how many persons who in are fact political prisoners might be imprisoned under the category of common criminal.

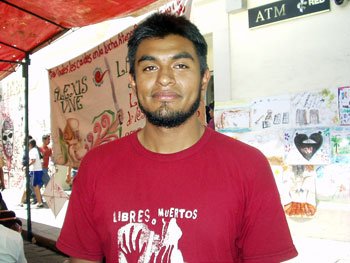

David Venegas Photos: D.R. 2008 Nancy Davies |

A forum was held in Oaxaca for three days, March 14, 15, and 16, for the specific purpose of coordinating planned strategies to obtain release for all the political prisoners across Mexico. A group inside Oaxaca’s Santa María Ixcotel prison planned and prepared posters. About fifty delegates attended El Foro de Articulación por la Libertad de los Pres@s Politic@s del País, most of them youngsters. Freedom for all prisoners, they say, is inextricably linked to building a new society.

Venegas Reyes, at the forum’s street tent set up between the local teacher’s union office (Section 22, a founding part of the APPO) and the HSBC bank, told me on Saturday, “I am free today because others helped.” He was referring to the determined efforts of not only his sisters and his lawyer, but also the APPO, including Section 22. “One person alone struggling to be released with dignity, the government will push down deeper,” he affirmed. By “released with dignity,” what did he mean? He obtained his liberty without “the gracious consent of the government, nor by a negotiation under the table.” He was grabbed on April 13, 2007 in the Llano public park by plainclothes officers of the Auxiliary, Bank, Industrial and Commercial Police (PABIC), and charged first with carrying drugs, and then successively with sedition, criminal association, and arson. When one accusation of a false criminal charge was nullified by the higher courts, the state governments fabricated another, thus the total of three additional accusations.

When Venegas was initially accused of carrying drugs, his family put down 4,000 pesos ($375 dollars) to get him freed on bail. However, the government immediately filed the other charges, so David was kept inside the Oaxaca prison of Ixcotel for eleven months. Eventually, Venegas says, that initial drug charge which is still in process will also be ruled illegitimate, and the 4,000 pesos will be returned. Maybe.

During the year’s imprisonment David never confessed to false accusations against him. “This naming a crime is the government’s way to criminalize social protests,” Venegas said.

In the same time-frame, four of the San Salvador Atenco (in Mexico state) prisoners were also released: Venegas was freed on March 5 and four Atenco people were freed on March 8, 2008. Forty-seven remain imprisoned in Chiapas, and jailed members of the Revolutionary Army of the Insurgent People (ERPI) include two Oaxaqueños. Venegas believes that bringing to bear international pressure, human rights commissions, and sound legal logic, all helped to gain releases for the four Atenco people and himself.

The forum, taking off from that point, has decided that international human rights pressure is effective – Mexico is a signatory to indigenous and human rights agreements – but it’s not enough. It named other areas which must be confronted, among them the media, which repeat criminal accusations against social protesters and use biased, denigrating word such as “riots” and “brutality”, effectively labeling protesters as criminals.

|

Forum participants watched a documentary film about Atenco on Friday evening, March 14. Sitting in the outdoor audience, I watched the scenes of violence on the screen with one thought: this film looks just like events in Oaxaca. The helicopters, the Federal Preventive Police (PFP), the beatings with clubs and guns, the kicking in of doors during illegal searches – all too familiar. Several of the forum participants were former Atenco prisoners, or prisoners from other areas where the social movement is active. Alongside them were other delegates from Tabasco, Chiapas, Mexico state, Mexico City and Oaxaca.

Also in the audience (and attending the forum) was the father of Alexis Benhumea Hernández, a National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM) student who was killed at the age of twenty in Atenco, Mexico on May 4. A gas canister shot by the Federal Preventive Police penetrated his skull. He died after some days in a coma. His father, Ángel Benhumea Salazar, was wearing a T-shirt with the words “Alex lives” stenciled on the front. Both Alex Benhumea and his father, Angél were affiliated with the Zapatista “Other Campaign.” Benhumea told me that La Otra is now a national presence, propelled by the anger against international capital and neoliberalism foisted onto workers and campesinos via the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). As Angél spoke he cradled in his arms an envelope filled with photographs of his dead son.

The campesinos of Atenco won a struggle against the federal government’s attempt to take their land for expansion of the Mexico City airport, in August of 2002. The repression in neighboring Texcoco on May 3, 2006, Angél affirmed, was provoked by the government when flower vendors were refused permission to sell their flowers as usual, in the market of Belisario Domínguez. The Peoples’ Front for the Defense of the Land (FPDT) came from its near-by Atenco base, to support their struggle, as did people from the Other Campaign.

Some from the FPDT also maintained that Texcoco wanted to rid itself of street vendors in order to attract a Wal-Mart. Whatever the truth of that may be, ultimately, 300 civilians faced off against more than 3,000 PFP, Angél Benhumea told me. At present, he continued, those who were involved have moved in different directions: some like himself stayed with La Otra, some have gone with the center-left Party of the Democratic Revolution (PRD), and some with underground guerrilla forces.

Ángel Benhumea |

For his part, Ángel cites a statistic of eight million campesinos impoverished by NAFTA and the use of cheap labor reserves in Mexico. Regarding the guerrillas, he said, “There are PFP all over the country; the people are going to mobilize” against the police. People are stashing weapons, he said, and they will affiliate with the guerrillas — in other words, he believes that Mexico may see armed uprisings.

The forum attendees scheduled a protest march and meeting for Sunday, March 16, the final day of their stay in Oaxaca. While waiting for the march to set out, Calypso Mejía Lopez, a forum attendee and organizer who is the sister of Adán Mejía López, spoke with me. Her brother Adán was arrested on narcotics charges, and at age twenty-five faces twenty-five years in prison (he is in Ixcotel) if the committee to free prisoners doesn’t get him released.

Calypso told me: “The struggle at the base is the struggle of political ideas against capitalism and neoliberalism.” According to Calypso, Adán is a member of the APPO as well as a Marxist. She repeated his recent words: “It’s important for me to get out, but it’s so much more important that the people continue organizing to win social demands and changes in the political system.” The siblings were not born Oaxaqueños; they came from Mexico City. Does that mean, “outside agitators”? I don’t think so. The Oaxaca struggle is considered part of the same national struggle to which Angél Benhumea alluded.

Calypso affirmed that the committee’s task to free political prisoners includes public discussions, where people, often family members like her, explain to the public what each prisoner is like: an individual human being with human rights. This requires that the political situation in Mexico be openly discussed – why are these people imprisoned? Many people, like David Venegas, were arrested because they were involved with the APPO. Similar arrests go on all over Mexico. The courts know it; that’s why eventually the criminal charges get thrown out. The Human Rights committees know it; especially because these “criminals” are often tortured. But when someone is thrown in jail as a “criminal,” most of the public don’t ask if that is justice – or what is going on. They don’t recognize these “criminals” as people like themselves, because the government label of criminal is rarely challenged.

Calypso Mejía Lopez |

The march from Llano Park met up with family and friends at the Ixcotel prison, on the highway outside Oaxaca city, for a crowd of about two hundred. Along the march route young graffiti painters left slogans, despite mournful appeals of private homeowners. McDonalds and the banks made no appeal; their painters disappeared the slogans an hour after they appeared. However, as is normal for Oaxaca, photographers and video makers captured many scenes.

This is a nation where social protest has been criminalized, according to the forum attendees. As David Venegas said, the forum and the self-organized Santa Maria Ixcotel Political Prisoners Committee are together formulating a program for struggle and a plan of action “to achieve liberty for all the men and women political prisoners, and to stop the militarization and the repression of social struggle.”

According to the El Enemigo Común website of February 19:

In Oaxaca alone, 28 social activists and comrades were imprisoned for political reasons. Seventeen of them remain in the Santa María Ixcotel Central Penitentiary: Adán Mejìa Lòpez, Vìctor Hugo Martínez Toledo, Miguel Ángel García, Pedro Castillo Aragón, Gonzalo López Cortéz, Isabel Almaraz Matías, Agustín Luna Valencia, Eleuterio Hernández García, Álvaro Sebastián Ramírez, Urbano Ruiz Cruz, Cirilo Ambrosio Antonio, Abraham García Ramírez, Fortino Enríquez Hernández, Ricardo Martínez Enríquez, Justino Hernández José, Estanislao Martínez Santiago, and Mario Ambrosio Martínez.In the Pochutla Regional Prison the following three comrades are held: Abraham Ramírez Vázquez, Noel García Cruz, and Juventino García Cruz. There is one prisoner in the Villa de Etla Penitentiary––Zacarías P. García López––and one more is in the Cuicatlán Regional Prison––Flavio Sosa Villavicencio. Four comrades are in the Tehuantepéc Prison: José Luís Sánchez Gómez, Amado Castro López, Nicasio Zaragoza Quintana, and Edmundo Espinosa Guzmán, and another is in the Juvenile Facility: Jaciel Cruz Cruz.

Click here for more Narco News coverage of Mexico

- The Fund for Authentic Journalism

For more Narco News, click here.