Emergence: An Irresistible Global Uprising

An Essay from the Book We Are Everywhere

The book We Are Everywhere can be purchased online through the Authentic J-Store at this link. |

By the Notes From Nowhere Collective

October 21, 2004

“It is not only by shooting bullets in the battlefields that tyranny is overthrown, but also by hurling ideas of redemption, words of freedom and terrible anathemas against the hangmen that people bring down dictators and empires.”

– Emiliano Zapata, Mexican revolutionary, 1914

The new century is three days old when the Mexican army encampment of Amadór Hernandez, nestled deep in the Lacandón jungle of Chiapas in the country’s southeast, comes under attack from the air. The air force of the indigenous Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN) swoops down in its hundreds on the unprepared troops.

This is an army of paper airplanes, which soar, curve, and dive in the dappled forest sunlight. Some are caught in the teeth of the barbed wire fence. Some fall to the forest floor, and are silenced. But many are well-thrown – they rise, dip, bank, and swerve past the bracken and black plastic sheeting straight into the army dormitories.

They are heavily armed with words of resistance and launched over the fence around the base by the local people, indigenous Tzeltals. For weeks, months now, they have been chanting, singing, crying to the troops – that they want peace. They want the low-flying military aircraft to stop terrorizing their village. They don’t want the army to build a road through their forest. They want their rights, their dignity as indigenous people. But their voices are lost in the damp canopy of forest as the camp commanders drown them out by blasting military marches, Musak, and the William Tell Overture over the PA system. And the soldiers are just children, far from home, frightened of the Zapatistas, who the state governor has warned are about to launch a violent attack on the base.

But now, finally, the Tzeltal voices have penetrated the fence of power with their message of resistance to the federal troops, and lampooned the hyped threat of Zapatista violence. On each plane is written the words: “Wake up! Open your eyes so you can see! Soldiers, we know that poverty has made you sell your lives and your souls. I also am poor, as are millions. But you are worse off, for defending our exploiters.”

A year and a half later on a shimmering hot day in July 2001, Air Force One carries George W. Bush into Christopher Columbus airport in the Italian city of Genoa for the G8 summit, where the eight most powerful men in the world are gathering to decide the fate of six billion human beings. They meet behind a vast, reinforced fence which marks the heavily militarized “red zone,” where democratic law has been suspended, expressing opinions on the fate of the global economy rendered illegal, and protest forbidden. It exists to keep 300,000 protesters away from the eyes and ears of the G8.

And so the Zapatista air force launches its second attack. These paper airplanes, covered with messages of resistance and colourful images of Zapatista rebels, have been carefully constructed by the small hands of school children in Oventic, an autonomous Zapatista community in the highlands of Chiapas, and posted to activists in Genoa. Arms curve, planes rise and fall, littering the ground inside and outside the red zone.

Once again, rebel voices breach the fence of the powerful.

But what is it that connects the Genoa protesters and the Zapatistas? To uncover the character of the world’s largest social movement, you must follow the flight of a paper airplane, from the Lacandón jungle in southeastern Mexico to the streets of the Italian port city of Genoa. It’s a paper airplane carrying a message of hope, and of resistance.

Breaking Fences

Protesters rip down the fence at the Woomera detention center, freeing many asylum seekers imprisoned under inhumane conditions. Australia, 2002. Photo courtesy of Desert Indymedia |

– Barbara Kingsolver, Small Wonder, Harper Collins, 2002

The fence surrounding the military base in Chiapas is the same fence that surrounds the G8 meeting in Genoa. It’s the fence that divides the powerful from the powerless, those whose voices decree, from those whose voices are silenced. And it is replicated everywhere.

For the fence surrounds gated communities of rich neighborhoods from Washington to Johannesburg, islands of prosperity that float in seas of poverty. It surrounds vast estates of land in Brazil, keeping millions who live in poverty from growing food. It’s patrolled by armed guards who keep the downtrodden and the disaffected out of shopping malls. It’s hung with signs warning you to “Keep Out” of places where your mother and grandmother played freely. This fence stretches across borders between rich and poor worlds. For the unlucky poor who are caught trying to cross into the rich world, the fence encloses the detention centers where refugees live behind razor wire.

Built to keep all the ordinary people of the world out of the way, out of sight, far from the decision-makers and at the mercy of their policies, this fence also separates us from those things which are our birthright as human beings – land, shelter, culture, good health, nourishment, clean air, water. For in a world entranced by profit, public space is privatized, land fenced off, seeds, medicines and genes patented, water metered, and democracy turned into purchasing power. The fences are also inside us. Interior borders run through our atomized minds and hearts, telling us we should look out only for ourselves, that we are alone.

But borders, enclosures, fences, walls, silences are being torn down, punctured, invaded by human hands, warm bodies, strong voices which call out the most revolutionary of messages: “You are not alone!”

For we are everywhere.

We are in Seattle, Prague, Genoa, and Washington. We are in Buenos Aires, Bangalore, Manila, Durban, and Quito. Many of these place names have been made iconic by protest, symbols of resistance and hope in a world which increasingly offers little room for either.

The Zapatistas have joined with thousands around the world who believe that fences are made to be broken. Refugees detained in the Australian desert tear down prison fences, and are secreted to safety by supporters outside. The poor, rural landless of Brazil cut the wire that keeps them out of vast uncultivated plantations and swarm onto the properties of rich, absentee landlords, claim the land, create settlements, and begin to farm. Protesters in Québec City tear down the fence known as the “wall of shame” surrounding the summit meeting of the Free Trade Area of the Americas, and raise their voices in a joyful yell as it buckles under the weight of those dancing on its bent back, engulfed in euphoria even while the toxic blooms of tear gas hit. The radical guerrilla electricians in South Africa break the fence of privatization that keeps the poor from having electricity by installing illegal connections themselves. Peasant women across Asia gather to freely swap seed, defying the fences of market logic that would have them go into debt to buy commercial seed. “Keep the seeds in your hands, sister!” they declare.

Those who tear down fences are part of the largest globally interconnected social movement of our time. Over the last ten years, our protests have erupted on continent after continent, fueled by extremes of wealth and poverty, by military repression, by environmental breakdown, by ever-diminishing power to control our own lives and resources. We are furious at the increasingly thin sham of democracy, sick of the lies of consumer capitalism, ruled by ever more powerful corporations. We are the globalization of resistance. But where we came from, what we have done, who we are, and what we want have remained untold. These are our stories.

An Army of Dreamers

Welcome to autonomous Zapatista territory: Chiapas, Mexico. Photo: Yuriria Pantoja Millán |

– Emma Goldman

Depending on who you ask, the resistance began 510 years ago when the indigenous of the Américas fought Columbus, or 700 years ago when Robin Hood rode through the forests of England to protect the rights of commoners, or a little over 100 years ago when slavery was abolished throughout the Américas, or 150 years ago when working people became an international revolutionary movement, or 50 years ago when colonized countries gained their independence, or 30 years ago when populations across Africa, Asia, and Latin America started rioting over the price of bread as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) began restructuring their economies.

Or perhaps it was in 1988 when the IMF and World Bank were almost run out of Berlin by 75,000 protesters, or 1999 when the same number disrupted the World Trade Organization (WTO) meeting in Seattle? For those who like their history neat, 1994 emerges as a landmark year as resistance to capitalism snowballed. Resistance to IMF policies in the global South increased dramatically that year; around the world there were more general strikes than at any previous time in the twentieth century according to the labor journalist Kim Moody; radical ecological movements were re-introducing creative direct action tactics to popular protest during in the US and the UK, and as the Mexican economy crashed and burned, the Zapatista uprising took the world by storm. For simplicity’s sake, let us start the story there.

As the clock chimed midnight on January 1, 1994, indigenous Zapatista rebels emerged for the first time from the mists of the Lacandón rainforest. The new year ushered in corporate rule in the guise of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), a treaty that threatened the Zapatistas’ land rights. Article 27 had been eliminated from the Mexican constitution – land reform fought for by Emiliano Zapata, folk hero and revolutionary, which created a nationwide system of collectively owned and cultivated land, and which was absolutely incompatible with NAFTA. And so a courageous band of women and men launched a unique resistance movement that was to reinvent the radical political imagination for the world.

Under the cover of night the Zapatistas took control of seven cities, set prisoners free, set fire to police headquarters and expropriated weapons found there, occupied City Halls, secured major highways, and declared war against the Mexican government and the policies they called neoliberalismo. Many were armed only with rifle-shaped sticks and toy guns. Their most powerful weapons were their words. They said they were “leading by obeying”; that they were invisible people who had “masked themselves in order to be seen”; that they didn’t want to seize power for themselves, but to break it into small pieces that everyone could hold. The war lasted for twelve days, until Mexican civil society demanded a cease-fire and peace negotiations, but the inspiration, the poetry, and the hope that run deep in the hearts of the Zapatistas was contagious, and the tale of the unlikely army found its way into the hearts and minds of activists around the world for whom hope had become a rare commodity.

At the time, the Zapatista uprising seemed to come from out of nowhere. The 1990s were a time of triumphant optimism for capitalism. The old enemy of the Soviet Empire had collapsed, and with it the remaining opposition to the capitalist system. Economic globalization – the imposition of the “free” market into every corner of the globe – was worshiped by economists as a kind of fundamentalist religion. Every piece of earth, every natural resource, and billions of pairs of human hands, feet, and backs became raw material to create products to sell on the global market, and that created growth, and growth, we were told, was good for everyone. Capitalism was so ubiquitous people forgot they were living under an “ism” – the time for all isms, in fact, seemed over.

During this period, the disappointed fragments of the left had either turned towards the ascendant neoliberal sun, or withdrawn into disillusion. They didn’t know what to do with the Zapatistas. As indigenous people, they didn’t fit into a Marxist model of proletarian revolution of the sort that had flourished in Latin America in previous decades. But as the embers of the old left faded, and capitalism declared itself immutable, inevitable, there were pockets of resistance abroad ready to hear a new story.

Or rather, stories. For the time of single ideologies and grand narratives was over. People were sick of sacrificing themselves for the sake of gigantic game plans which didn’t account for their individual needs, their humanity, their culture, their creativity. They were unwilling to be soldiers or martyrs in movements whose big-picture and top-down solutions were to be imposed on the “masses,” which too often existed only in the imaginations of vanguard revolutionaries. People had grown weary of being ordered about, whether by their oppressors or their self-appointed liberators.

Into this chapter of history entered the Zapatistas, masked people the colour of the earth, women wearing multi-coloured clothes and carrying make-shift weapons, and speaking a quite different language of resistance – of land, poetry, indigenous culture, diversity, ecology, dignity. The Zapatistas understood the power of subjectivity, spoke the language of dreams, not just economies.

Though their army had a hierarchical command structure, the communities they represented had no leaders, only those who led by following the will of the people, who demanded an end to the war, and who have led the army into pursuing an unusual path towards peace – a true peace, which includes dignity and justice, which has no room for hunger, for death by military and paramilitaries, or loss of their land. They did not march on the capital to seize the state, nor did they want to secede from it. What they wanted was autonomy, democracy, “nothing for ourselves alone, but everything for everyone.”

Activists from around the world declared their solidarity with the Zapatista autonomous zones, and asked: “What do you want us to do?” The Zapatistas, taken aback by so much attention, replied that for them, solidarity would be for people to make their own revolutions in ways which would be relevant to their own lives. As one activist put it: “The Zapatistas translated struggle into a language that the world can feel, and invited us all to read ourselves into the story, not as supporters but as participants.” And in doing so, the Zapatistas unleashed an international insurrection of hope against the forces of global capital.

In 1998, a year before protesters shut down the meeting of the WTO in Seattle, Subcomandante Marcos, military strategist and spokesperson of the Zapatistas, said: “Don’t give too much weight to the EZLN; it’s nothing but a symptom of something more. Years from now, whether or not the EZLN is still around, there is going to be protest and social ferment in many places. I know this because when we rose up against the government, we began to receive displays of solidarity and sympathy not only from Mexicans, but from people in Chile, Argentina, Canada, the United States, and Central America. They told us that the uprising represents something that they wanted to say, and now they have found the words to say it, each in his or her respective country. I believe the fallacious notion of the end of history has finally been destroyed.”

“The naming of the intolerable is itself hope,” wrote John Berger. With their uprising the Zapatistas named an old enemy in new clothing – neoliberal globalization. Their rebel yell: “Ya Basta!“ (Enough!) announced the end of the end of history. This cry, and their communiqués posted on the internet, echoed around the world. They were heard by urban street reclaimers in London; by land squatters in Brazil; by Indian farmers burning genetically modified crops; by hackers, cyberpunks, media guerrillas; by Seattle anarchists; by Africans rioting against the IMF; by white-overalled Italian dissidents. Not a homogenized band of revolutionary proletariat, but a diverse band of marginal people – vagabonds, sweatshop workers, indigenous peoples, illegal immigrants, squatters, intellectuals, factory workers, tree-sitters, and peasants.

History, like resistance, began to accelerate. In 1996 the Zapatistas called this diverse band to an “International Encuentro (encounter) Against Neoliberalism and For Humanity” in the rainforests of Chiapas; this was the historic moment when these rebels recognized each other and their common enemy. Also in 1996, arguably the first tear gas-wreathed summit of the globalization era was held in Manila in the Philippines, when 10,000 protesters against the Asia Pacific Economic Community (APEC) meeting faced 30,000 police and soldiers, the slums were bulldozed to sanitize the city, and dissenters filled the jails. In 1997 another Zapatista-inspired Encuentro led to the creation in 1998 of Peoples’ Global Action, a network of grassroots social movements who swore to resist capitalism with direct action, whilst throughout 1998 unrest and wave upon wave of strikes and “people power” uprisings in the wake of financial crisis broke across South East Asia. The networks strengthened further as internationally coordinated days of action targeted the WTO in May 1998 and the G8 in 1999 with a global “carnival against capital.”

But the anticapitalist movement only became visible to the Northern media during spectacular moments of confrontation at global economic summits in the rich world. The first to make it onto their radar screen was on November 30, 1999 when the WTO meeting was rudely interrupted in Seattle.

The city ground to a halt when a new generation of activists, using radically decentralized, creative tactics, outwitted the police and successfully prevented the WTO from launching a fresh round of free trade negotiations. Locked-down, tear gassed, and beaten with truncheons, they blocked the WTO delegates’ way to the conference center, argued with them about patents on life, the global forest logging agreement, and enforced privatization. They insisted that their world was not for sale. Business leaders looked on, stunned. None of them could tell if Seattle was a carnival or a riot, where it had come from, or who these people were. It was an epic confrontation to decide who would go forth into the new century ascendant – people or corporations.

US Trade Representative Charlene Barshefsky, due to greet 5,000 international trade delegates at the summit’s opening ceremonies, was trapped in her hotel room by the street blockades, as was US Secretary of State Madeleine Albright. By 10:00 am, Albright was screaming down the telephone to the governor to call in the National Guard. At 10:05 am the tear gas started. Mass arrests, concussion grenades, curfews, plastic bullets, beatings, and prison followed for many of the protesters, hundreds of whom refused to give their names when arrested. The police entered them on the arrest records as “John/Jane WTO.” A few days later, the summit ended in failure – collapsing from within while attacked from without. “The twenty-first century started in Seattle,” ran the headline of French newspaper Le Monde the following morning.

Together, through the process of international gatherings, global networking, and joint mass actions, the movement has created a rich fabric, both strong in its global solidarity and supremely flexible in its celebration of local autonomy. This global fabric of struggle breaks with single-issue politics, transcends divisions of class, race, language, religion, and nationality, is strengthened by diversity, stretches around the globe, and yet is the natural outgrowth of resistance cultures as different as Korean auto-parts manufacturers, indigenous Andean farmers, and European squatters.

Rule of the Market, by the Market

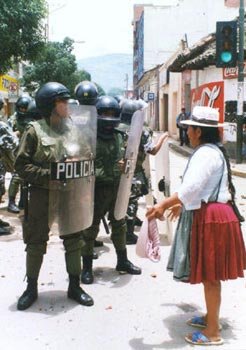

A woman confronts the police during the popular uprising against the privatization of water. Cochabamba, Bolivia, 2000. Photo: Tom Kruse |

– Philippines government advert in Fortune, placed in 1975

Neoliberalism, an economic theory which is the latest incarnation of capitalism, means rule by the market. In other words, the market should be the predominant arbiter of all the decisions in a society.

The central fact of our time is the upwards transfer of power and wealth – never have so many been governed by so few. The economy has globalized but in this new world order there is no room for people. We are ruled over by transnational corporations and the World Trade Organization, the World Bank, and the International Monetary Fund; our lives can be ruined at the whim of the financial markets. In their view, a deregulated, privatized, corporate-led global “free” trade regime is the answer to humanity’s problems.

But “free” trade is on an inevitable collision-course with democracy. For history shows that the exercise of genuine democracy will always act as a brake on the free market. The dawning of the twentieth century saw – along with deepening democracy and universal suffrage – an increase in social safety nets for the working poor. All this has be e n rolled back since the 1980s by the advent of neoliberalism. As economies are liberalized and public assets sold off, political freedoms are increasingly curtailed and the state is employed in keeping down the objections of its own protesting populations. The key decisions of our lives do not belong to us. We are the uninvited, standing on the peripheries as others shape the world in their own image. We are disconnected from what we produce and what we consume, from the earth and from one another. We live in an arid, homogenized culture.

Neoliberalism achieves this by use of its two most potent weapons. Firstly, messages of prosperity – we can all have what the rich have, as long as we keep our heads down and keep working. Secondly, when this doesn’t work, economic muscle. Between 1990 and 1997, “developing” countries paid out more in servicing their debt than they received in loans – a transfer of $77 billion from South to North, through the machinery of the IMF and the World Bank – organizations which ensure the continued dominance of the rich nations. Meanwhile, ironically, those rich nations are being “structurally adjusted” too, as the World Trade Organization rolls back democracy in the name of trade, unraveling decades of social progress.

Ours is the complex task of resisting this power exercised through a web of political, economic and military systems, representing entrenched and often invisible interests. In a global economy, there is no seat of power for the new guerrillas to storm. This is why protesters have been targeting international summit meetings. Unaccountable institutions that determine the fate of the global economy – the World Trade Organization, the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund, the G8, the World Economic Forum – have not been able to meet in recent years without being accompanied by protest.

The spectacle of carnivalesque theaters of popular democracy outside these summits contrasts sharply with the undemocratic and secret negotiations of trade ministers and corporate lobbyists going on behind the police lines. These tactics are potent weapons, unmasking the true nature of neoliberalism’s economic mythologies and institutions, and simultaneously blowing apart the cultural malaise of late capitalism with authentic cries of rebellion, of culture re-engaged with the real.

For together we are the inversion, the mirror opposite, of a strata of concentrated power from above, in which decisions that affect billions of human lives are made at a transnational level where the market is king. We embody the real world below, the sphere of all those factors not reducible to a commodity to be bought and sold on a global marketplace; human beings, nature, culture – an international multitude that in its diversity challenges the idea that the global surfaces of the world market are interchangeable.

Dollars in the Soil

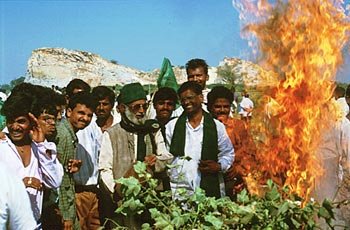

The Karnataka State Farmers’ Movement (KRRS) burn genetically modified crops as part of the “Cremate Monsanto” campaign. Karnataka, India, 1998. Photographer unknown |

– Declaration of South American Chemical and Paper Workers

In April 2001, a few weeks before thirty-four heads of state met in Québec City to hammer out details of trade liberalization throughout the western hemisphere, a mob of merry men and women dressed as Robin Hood and Maid Marian occupied the Pacific Stock Exchange in San Francisco, demanding that the secret negotiating text of the Free Trade Area of the Americas (FTAA) be released to the public. As he was carried away by police officers, one Robin Hood yelled: “I do not recognize the authority of the Sheriff of Nottingham!” The bemused police bundled him into the back of their van as he shouted to the cheering crowds, “Robin Hood will be back!”

In thirteenth-century England, Robin Hood and his band of merry men defied the authority of the Sheriff of Nottingham, but not just by robbing the rich to feed the poor. One theory suggests that Robin Hood is a fable of resistance against the ruling classes’ policy of transforming common land available for the use of all, into fenced-off grazing areas for sheep to encourage the native wool industry for their own private gain. This process, known as “enclosure,” remains one of the most powerful concepts in understanding contemporary capitalism, just as tearing down fences is one of the most powerful symbols of resistance to enclosure.

These unprecedented enclosures were precursors to mass clearing of the lands of peasants, and the eventual ushering of these people into the cities to become the factory workers of the industrial revolution where their labor, too, became an “enclosed” commodity. The dramatic upheaval of industrialization in Britain between 1785 and 1830 was the first of its kind in the world. Sweeping Enclosure Acts led to millions of acres of commonly held land being fenced off, pushing people off land, taking away their common rights of usage: collecting fire wood, growing crops, grazing animals, gathering food, hunting, and fishing. Over half of all cultivated land in England was put into private hands, until no county had more than three percent of its area held in common. An entire class of people experienced a loss of independence and freedom, traditions of local exchange and mutual assistance were shattered, and formerly self-sufficient people became wholly dependent on what they could earn and buy in a cash economy.

Compare this to the contemporary process by which communal lands from Africa to the Pacific are torn apart under the World Bank and IMF’s Structural Adjustment Programs. The Economist magazine invoked the fence of capital when it declared that Africa’s land, “must be enclosed and traditional rights of use, access and grazing extinguished,” as it is “private ownership of land that has made capitalism work.”

And so the peasant, indigenous, and social movements of the South are facing something similar to the first wave of enclosure in rural England; they are being thrown off their lands, and having their rights to water, to pasture, to forests, to seeds taken away from them. Via Campesina, the international peasant farmers union uniting farmers, rural women, indigenous groups, and the landless is one of the most extraordinary examples of the movements’ capacity for international networking – a veritable international peasants’ revolt in the making. With a combined membership of millions, from Brazilian landless to Indonesian farmers, it represents probably the largest single mass of people opposed to the WTO. The first points of resistance to global capitalism have been those who still depend upon natural resources directly for their livelihoods.

Meanwhile, in post-industrial societies which went through this process hundreds of years ago, today neoliberalism is penetrating the everyday, having to “enclose” new areas of our lives, areas previously unimaginable. From the invasion of the material fabric of life through the patenting of gene types, from the opening of markets in health, social care, and education through to the assertion of intellectual property rights over medicines – all are tainted by the logic of capital and the elevation of the commodity above all else.

As a result the Northern post-industrial rebels against enclosure began as culture jammers, software hackers, GM crop-pullers, road protesters. Making the connections, Native American poet John Trudell calls them “blue indians,” because, he says: “The world is now an industrial reservation and everybody is the Indian, and our common colour is the blues.”

These two groups; the natural resource-based movements – the indigenous, the farmers – of the South, and the post-industrial marginalized of the North, have somehow recognized in one another a shared enemy – global capital. Suddenly, the “blue indians” and the real Indians are speaking the same language. Subcomandante Marcos rejects the “plastic playlands” of corporate development that will dispossess the people of Chiapas of their land, while Northern anticapitalists reject the spectacles of consumer capitalism, those same plastic playlands that have covered every inch of their towns, and their souls. Together they are creating a movement of movements that defies easy classification, a rebellion whose character is one of anarchic hybridity, a potent mixture of the symbolic and the instrumental.

All over the world similar struggles, struggles against the commodification of every aspect of life, are being waged every day. A poster attached to the fence in Québec City read, “Capital is enclosure: First it fenced off the land. Then it metered the water. It measured our time. It plundered our bodies and now it polices our dreams. We cannot be contained. We are not for sale.” Unbeknown to each other, a Thai rural coalition, the Assembly of the Poor, had used almost the same terms one year earlier. When thousands of rural Thais – farmers, fisherfolk, the landless – converged to protest against the Asian Development Bank meetings in Chiang Mai in May 2000, they carried a tombstone on their backs inscribed with the words, “There is a price on the water, a meter in the rice paddies, dollars in the soil; resorts in the forests.”

Spaces of Hope

Under the hooped skirt, Reclaim the Streets plant trees in the fast lane of the M41 highway. London, UK. Photo: Julia Guest |

– Iain A Boal, First World, Ha Ha Ha!, City Lights, 1995

One of the great strengths of this movement of movements has been its capacity to rekindle the idea of a global political project defined by notions of diversity, autonomy, ecology, democracy, self-organization, and direct action. This activism is an attempt to intervene directly in the process of corporate globalization. These spaces of hope are reclaimed urban streets, the de-privatized wells and irrigation canals of Cochabamba, in Bolivia, the community gardens of New York City, the appropriated farmland of the Landless Workers Movement of Brazil, the open publishing wire of the Indymedia websites.

Against the single economic blueprint where the market rules, we represent diverse, people-centered alternatives. Against the monoculture of global capital, we demand a world where many worlds fit.

Today, the different movements around the world are busy strengthening their networks, developing their autonomy, taking to the streets in huge carnivals against capital, resisting brutal repression and growing stronger as a result, and exploring new notions of sharing power rather than wielding it. Our voices are mingling in the fields and on the streets across the planet, where seemingly separate movements converge and the wave of global resistance becomes a tsunami causing turbulence thousands of miles away, and simultaneously creating ripples which lap at our doorstep. Resisting together, our hope is reignited: hope because we have the power to reclaim memory from those who would impose oblivion, hope because we are more powerful than they can possibly imagine, hope because history is ours when we make it with our own hands.

This essay opens the chapter “Emergence” in the book We Are Everywhere. Other stories in this chapter include:

- “Over the Wall: so this is direct action!” by Noam Levin, UK

- “Tomorrow Begins Today: invitation to an insurrection” by Subcomandante Marcos, Mexico

- “The Sans-Papiers: a woman draws the first lessons” by Madjiguéne Cissé, Senegal/France

- “The Sweatshop and the Ivory Tower“ by Kristian Williams, US

- “Reclaim the Streets: an arrow of hope“ by Charlie Fourier, UK

- “Direct Action: Street Reclaiming” by Notes From Nowhere

For more information about the book We Are Everywhere, see the book’s website. For a special offer to purchase a copy of the book, the Authentic J-Store is now open at Salón Chingón.

Essays from We Are Everywhere on Narco News:

Narco News Publishes Seven Essays from We Are EverywhereEmergence: An Irresistible Global Uprising

Networks: The Ecology of the Movements

Autonomy: Creating Spaces for Freedom

Carnival: Resistance Is the Secret of Joy

Clandestinity: Resisting State Repression

- The Fund for Authentic Journalism

For more Narco News, click here.