The Criminalization of Social Movements in the Andes

Pacho Cortés Case Part of a Wider Campaign in the Region

By Tigran Feiler

2004 Narco News Authentic Journalism Scholar

August 8, 2004

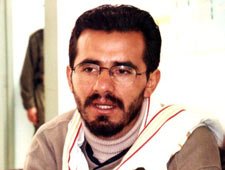

Colombian peasant leader and human rights activist Francisco “Pacho” Cortés was arrested in El Alto, Bolivia on April 10, 2003 together with Bolivian coca growers Carmelo Peñaranda and Claudio Ramírez. The police claim to have found 2 kilos of cocaine, terrorist manuals, weapons and false documents in Cortés’ home. The three were accused by the Bolivian authorities of terrorism, armed uprising, drug trafficking and espionage. Cortés, Peñaranda and Ramírez have denied the charges, claiming that they are political prisoners. The detentions have continued and today a total of 48 Bolivian peasant leaders, the majority of them coca growers, are being processed.

Pacho Cortés Photo: Narco News Agency D.R. 2004 |

The Bolivian media first claimed that Cortés had connections to Colombia’s major guerrilla group FARC (Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia). The prosecutor accused Cortés of planning to “form irregular groups, guerrillas and terrorists” in Bolivia under the ideological influence of Colombia’s second largest guerilla force ELN (National Liberation Army). Cortés was accused of trying to establish ELNB, a Bolivian branch of ELN, and the prosecutor stated that he ”is and has been an active member of ELN…camouflaging his activities under the facade of an activist in social peasant organizations.”

Cortés, a respected leader in his native Colombia for over 20 years, has participated in peace encounters and meetings against the Free Trade Area of the Americas and Plan Colombia. His life has been repeatedly threatened by Colombian paramilitary and his family was included in the U.N.-sponsored Program for Protection of Human Rights Defenders. At the beginning of 2003 Cortés moved to Bolivia after receiving new death threats.

The arrest of Cortés has caused international upset. Various Colombian organizations have protested against the arrest, and an international solidarity mission for his release was created. In a letter demanding the release of Cortés signed by peasant leaders from Latin America and France, among them José Bové, they stated that “in Bolivia a strategy of criminalization and litigation of the social movements is implemented, which tries to contain the legitimate and just social protest, for human rights, dignity, territory, sovereignty and peace.”

Rose Marie Achá Photo: Noah Friedsky D.R. 2004 |

They are looking to make an impact both on the Bolivian and the international level, she concluded.

In Colombia, where over 90 percent of the world’s assassinations of trade union members take place; the persecution of the social movements was given a new ideological framework in 2003. According to a report published by the organizations in the Colombian Platform for Human Rights, Democracy and Development in September 2003 the human rights situation in Colombia worsened after Alvaro Uribe Vélez became president in 2002. Uribe Vélez responded in an infamous speech on September 8, 2003 where he called human rights groups “spokesmen of terrorism” and ‘human rights traffickers’. A couple of days later Uribe Vélez specifically pointed out the respected Colombian Lawyers Collective José Alvear Restrepo as “mouthpieces of terrorism.”

In Ecuador the influential indigenous movement is also coming under increased attack. On February 1, the leader of the country’s main indigenous organization CONIAE, Leonidas Iza, suffered a failed assassination attempt in Quito, the country’s capital. On July 22, as the second indigenous summit was being inaugurated in Quito, the offices of the Indigenous Parliament were assaulted. Computers, a fax, and all the organizations archives were stolen. “This is a work of the government, they conduct a permanent persecution of the leaders of the indigenous movements,” Ricardo Ulucango, president of the Indigenous Parliament and Ecuadorian MP, said after the incident.

Nelson Palomino, the national leader of the confederation of Peru’s coca growers CONPACCP, was arrested on February 21, 2003. Palomino’s arrest came after several days of protest in one of Peru’s traditional coca growing areas. Palomino was accused of a number of crimes, among them terrorism, kidnapping and disturbing the November 2002 municipal elections. On May 24, 2004 Palomino was sentenced to 10 years in prison by a court in Ayacucho. The coca growers reacted to the sentence with a number of protests and Palomino said that he would appeal the decision not ruling out taking the case to the Interamerican Court of Human Rights.

Also in Bolivia the coca growers are suffering governmental repression. Margarita Terrán, a coca leader in the Chapare-region who was jailed in 2001, describes the war on drugs in Bolivia as “a political process to behead the social movements.”

According to Silvia Rivera, a professor of sociology at the San Andrés University in La Paz, the repression of the coca growers accelerated after the United Nations’ Special Assembly on Drugs in 1998 where the use of force was authorized to eradicate al coca in ten years. “The coca growers are being attacked because their public legitimacy and political presence in Bolivia and Peru is growing,” Rivera explained.

There is a new political and legal climate in Bolivia, according to Achá. “No one had been charged with terrorism since the early 80s, until recently.” All the Bolivian government’s intelligence groups and Special Forces receive financing and training from the U.S., so the same tactics is being implemented here, she added.

Evo Morales, the national leader of the Bolivian coca growers, explained how legitimizing the persecution of Bolivia’s social movements has changed over the years.

The well-organized miners during the 1950s and 1960s were permanently accused of being communists, then comes the theme of drug trafficking and since September 11, 2001 we are not only drug traffickers but also terrorists, he said.

“Drug terrorism is for Latin America what the weapons of mass destruction is for Iraq.”

- The Fund for Authentic Journalism

For more Narco News, click here.