The Condor Flies

Gliding on Narco News' Wings through the Coca-Growing Chapare

By Al Giordano

President, School of Authentic Journalism

August 6, 2004

COCHABAMBA, BOLIVIA, AUGUST 6, 2004: The condor, that giant, sacred, bird of these Andes, does not easily attain flight. The breadth of her wings is longer than her length from head to tail. To fly with a wingspan of up to 10 feet, she requires either a thermal updraft along high cliff… or sufficient runway to hop and run to flight speed. Once in the air, a condor doesn’t need to flap her wings… she glides overhead. She parachutes down from the side of the cliff, spreads her limbs, and the winds carry her forward and upward. People point to the skies and note how graceful, how easily she sails the wind, without having to flap her wings to move effortlessly from point to point.

But to watch a condor on flat land attempt to fly offers a distinct vision of this legendary creature. She must run, awkwardly, burdened by the excess size and weight – up to 33 pounds – of her gigantic wings, on a flat and arid plain, in order to achieve take-off… and to watch the condor rise up from below, from the ground, kind reader, is to truly know the condor’s might: her stubborn persistence and unconquerable will. Then you will know: her divinity is just one percent grace… and ninety-nine percent perspiration.

The Andean Condor is classified as an endangered species. National Geographic notes that the Andean condor, once a common site, faced near-extinction in recent years and now, “biologists in Venezuela, Colombia, and Ecuador are now busy reintroducing young condors hatched in North American zoos to fill in the current gaps in the birds’ historical distribution in South America.”

The Authentic Journalist, too, stood at the abyss of extinction few years ago, and the Narco News School of Authentic Journalism has also been busy reintroducing young auténticos and auténticas to the region, preparing them to fly, together, the big condor that is the Authentic Journalism renaissance.

Our condor, The Narco News J-School, here in the heart of the Andes mountain range, has spent the past week gaining traction and speed on the ground and has now achieved flight. It was a long and arduous, stumbling and bumpy, push and shove on the runway to get here, now, sailing and circling our América with the wide vista that can only be achieved by the many working together, and never by the few. All flights, after all, begin from below. The hard part is not the flying, but, rather, the takeoff and landing. Come with me, kind reader, and look through this condor’s eyes, together with the 60 plus Authentic Journalists who have now spent one week together – with three days left to go – getting this bird off the ground.

From these heights, we have seen a gateway to the vast Amazon jungle, in the tropical lands of Bolivia’s Chapare region… the winding rivers – tributaries to the planet’s greatest waterway – and the dense, green, rainforest. Over there, look! We see a farmer in his field… if you can call it a field… it is a tiny square plot, really, just ten yards by ten yards… behind what looks like a woodshed but is in fact his family’s home… he is joined by half-a-dozen neighboring farmers, who must also hide their tiny plots near trees and behind ramshackle homes… because the Bolivian armed forces and police keep coming to destroy his and their crop of coca bushes as part of the U.S.-imposed “war on drugs.”

And here come sixty outsiders to see him. They come from all parts of this continent and beyond, carrying weapons: microphones, cameras, tripods, minidisc recorders, digital devices, pens and notebooks… The farmer smiles: they are here not to report a sensational “expose” revealing the location of his coca plot, but, rather, to do what Commercial Journalists so seldom do: listen to him, to his neighbors, to the land, and to this humble shrub that is the cause of billions of dollars in fretting and warring, while at the same time it is not just cause but effect.

Charlie Hardy, the former Catholic priest and columnist known as the Cowboy in Caracas has come from Venezuela. He translates the farmer’s words, phrase by phrase, methodically, carefully, accurately, so that all the journalists – about one-third of whom do not speak fluent Spanish, and 95 percent of who don’t understand the farmer’s native Quechua language, may understand him.

As he and the other members of his “syndicate,” – a term, Charlie interjects, that has a slightly different context than in other lands… here in the Chapare, a syndicate is a grouping of 25 peasant farming families, a unit of organization and self-defense that, like the Amazon’s tributaries, join with hundreds of other such syndicates to fight for their lives and livelihoods against the destruction of the drug war – tell of their problems with the soldiers who come, again and again, usually at dawn, to uproot the fruits of their labor under the heavy Chapare sun.

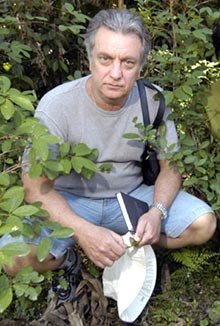

Walter Maierovitch Photo: Jeremy Bigwood D.R. 2004 |

But this was on Tuesday, August 3rd, when the condor was still taking off… and there are bumps on the runway… One of the students in the video and documentary filmmaking workgroup – where all had agreed to share their footage to produce, together, a documentary this week – took the video of the Maierovitch interview in the coca field and sent it, via Internet, to the Commercial Internet news site Terra.com and its “Jornal do Terra” (“Earth Journal”) online TV news program, without consulting with his fellow and sister team members. Within hours, Jornal do Terra blasted the video on its front page as a “world exclusive” report of its own. The TV anchorman, reading aloud a blatant lie, announced that, “a team from Jornal do Terra went to Bolivia and found hundreds of coca plants,” then presenting Maierovitch as the reporter on a video in which, in reality, he was being interviewed. This now serves as an example of the kind of sensationalist and yellow journalism, driven by hype and simulation, that the Narco News J-School sets out to destroy. That our own team’s work was obtained, then misrepresented, by Jornal do Terra continues to be a topic of reflection and discussion in the documentary group and among other J-Schoolers: What kind of journalism do we want to make? (Memo to Terra: you’ll be hearing from our lawyers if we don’t see the video credited to its true source shortly.) In any case, it was only part of our team’s interview, and the true and accurate context of it will be seen and heard soon enough on these Narco News pages through the documentary already in post-production.

Update: Well, that didn’t take long… By 4 p.m. on Friday afternoon, having heard our complaint echo from the Andean mountains, the Jornal do Terra website added a disclaimer to what, the previous night, it had heralded as an exclusive report: “The production of this report in the Chapare counted with the support of the School of Authentic Journalism that is being held this year in Cochabamba, Bolivia, between July 30 and August 8.” Once again, I remind the scholars of our J-School motto: “Here we don’t cry, we fight.”

Nicolau dos Santos Soares Photo: Jeremy Bigwood D.R. 2004 |

Twenty minutes later it is now time for the two Narco News buses – smoking and nonsmoking – to head for our next appointment, twenty minutes up the cobblestone road. “Where’s Natalia? Where’s Nicolau? Where are Wilkins and Chalo and Irene?” There is worry in the eyes of some of their new friends. They look to the chief – that’s me – each having heard from me, four days prior, the “First Commandment” of the Narco News School of Authentic Journalism: “Be punctual. If you miss the bus, the bus leaves without you.”

Egberto Winston Chipani Photo: Jeremy Bigwood D.R. 2004 |

Jeremy Bigwood Photo: Noah Friedsky, D.R. 2004 |

Natalia Viana and Amber Howard with Colonel Dario Leigue Photo: Jeremy Bigwood D.R. 2004 |

In downtown Villa Tunari (population: 1,500 families), where our troops stayed two nights at the Hostal San Antonio, the Posada Casa Grande and the Bibosi Hotel (Narco News thanks the workers and owners of each of these fine establishments for making our stay in the Chapare go so well), we also held long plenary sessions, hearing from, and asking so many questions of, coca grower leaders like Leonilda Zurita (the only accused “narco-terrorist,” to my knowledge, that has penned an op ed piece for the New York Times) and Margarita Teran, the 22 year old firebrand who moved our student and translator Karla Aguilar to tears during her descriptions of the horrid tortures against her when she has been brought to prison. Karla later explained to me: “Being from El Salvador, where there has been so much torture, I hate to have to translate this kind of information although I know it is important. I just can’t be a cold, objective, journalist about torture.” I beam at her because she is a real journalist. Anybody who can be cold and objective about torture isn’t even an authentic human being, much less a journalist.

Karla Aguilar Photo: Jeremy Bigwood D.R. 2004 |

Of course, no trip to the Chapare would be complete without descending on a local chicheria – a bar that serves chicha, a local drink fermented from corn or other plants – where students and professors alike danced and reveled until we closed the place. Cochabambinas Maria Eugenia Flores Castro and Leny Olivera served up the chica in buckets and taught authentic traditional dance steps to pop cumbias blasting from the boom box… the custom is to drink the chicha from dried jicama shells, offering the cup of chica to a friend, who then downs it in one gulp… and suddenly people who spoke only Spanish, or English, or Portuguese… or Quechua… could begin to understand each other better through the languages of dancing, of laughter, and of mutual aid… All for one, and one for all, the J-School spirit emerges on the edges of the Amazon… “Things of this land,” as they say in Chiapas… and also in the Chapare… as the condor begins again to take flight…

- The Fund for Authentic Journalism

For more Narco News, click here.