Bolivia: Real People Who Are Winning Elections

A Case Against Political Leaders Seeks to Criminalize Democracy

By Al Giordano

Part III of a Narco News Investigative Series

February 26, 2004

COCHABAMBA, BOLIVIA; MONDAY, 6:00 P.M., JANUARY 26, 2004: At the headquarters of the Six Federations of Coca Growers of Bolivia’s Chapare region, various leaders have just finished a meeting, and file into the office to meet with two reporters for Narco News. We asked to speak with those who, last December 11th, were charged as “terrorists” and accomplices of Pacho Cortés, to hear their accounts of what happened on that morning, before sunrise, when the police and prosecutors raided their homes and placed them under arrest.

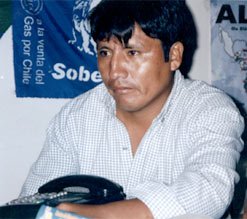

Marta González Photo: Alex Contreras Baspineiro D.R. 2004 |

“At 5:30 in the morning on December 11, they came to my house. There were two prosecutors, a man and a woman, and a large group of soldiers. The arrest warrant said they should get me between 7 a.m. and 7 p.m., but there they were, at 5:30 in the morning. They brought five military trucks and six jeeps of soldiers who surrounded my house. My mother and my son were there, too, but they didn’t let anybody move or come near the house.”“They burst in, guns drawn, shouting, ‘Don’t move! You have dynamite! You have cables! You have landmines!’ They handcuffed me as they searched my house. There were no explosives or weapons, though, just some used batteries from the garage, and they took any kind of electronic cables from the appliances. They also took my books about Plan Colombia, about Cuba. They took my passport, all my IDs, my cell phone, and my camera. They then took me to a car and by 6:30 a.m. I was in a jail cell in Chimoré.

“From the military base at Chimoré, later that day, they put us on an airplane. At 3:15 we arrived in La Paz. The press was waiting. They chained us together and pushed us rapidly to keep us from talking to the press. We were brought in front of the judge and there was a table filled with our cables, our batteries, photos, plus a mountain of old guns that weren’t ours. They didn’t show the judge the books and other things that they seized from us, just anything they could say was for weapons. The prosecutor said I was the author of various crimes. To the government, it’s a crime to be a leader, to lead a coca growers’ movement. They know that we’re advancing on the national and international levels, so they want to discredit us.”

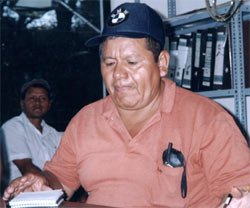

Pedro Calderón Rosas Photo: Alex Contreras Baspineiro D.R. 2004 |

Among the eight detainees of that morning, Pedro is the only one that did own a gun, and he freely admits it, noting that he’s had it for years, “an old escopeta,” which is a double-barreled shotgun of the type used by hunters. “Of course they took that. They also took new batteries I had in boxes, and 30 videocassettes. They took them all, along with my personal documents. The raid lasted an half hour.” He continues:

“During all the raids that morning, one of the police trucks had a crash, and a soldier died. When we got to the jail they yelled at me, accusing, ‘You killed that soldier!’ Of course I was never charged with that. The press came, but they didn’t let us speak. They put brand new dynamite on the table for the judge to see as part of the montage. All they got from us, in addition to my shotgun, were old nails, bicycle parts, and a tape recorder, that sort of thing. If I was going to attack the State, considering the weapons that they have, would I rely on an old shotgun? The real injustice here in Bolivia is to be poor.”

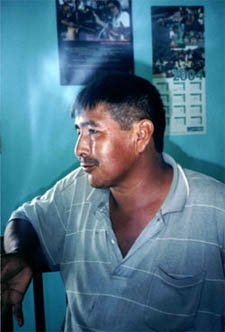

Eulogio Toco Photo: Alex Contreras Baspineiro D.R. 2004 |

“I went out to eat dinner in the street after watching the nine p.m. news. I had bread with sausage, and a soft drink. There, in the street, three men in uniform surrounded me, saying ‘There’s a warrant for your arrest.’ It was 1:30 in the morning, in a public avenue. They told me I was being charged with possession of controlled substances and brought me to the Chimoré jail. When I was in the cell they said, ‘You must have drugs on you. If you don’t have anything on you, we’ll free you.’ I had nothing illegal, only 160 Bolivianos (worth about twenty dollars) and a hundred dollars in American money, which they took from me. The prosecutor said to Lieutenant Alvarez, ‘Lieutenant, accompany him to the roadblock.’ As they were processing my papers so I could leave, I saw other police waiting outside, who arrested me again. One said ‘I’m a prosecutor from La Paz,’ and they put me back in the cell. Pedro Calderon was also in the cell and other compañeros were being brought in.”

CHIPIRIRI, THE CHAPARE REGION, BOLIVIA; THURSDAY, 11:00 A.M., JANUARY 29, 2004: While your reporter wraps up a series of meetings with Egberto Winston Chipana Dimachi, the director of Radio Soberanía (“Radio Sovereignty”), and one of the featured professors at the next session of the Narco News School of Authentic Journalism, a man in sandals comes walking up the dirt road toward the station. His name is…

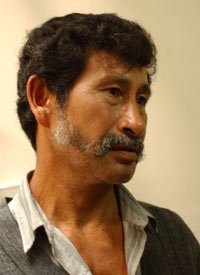

LEONARDO MARCA, 43, FATHER OF FIVE KIDS, explains:

“They came to my house at 6:15, a.m., on December 11th. I was about to have breakfast. Anti-drug police had surrounded my house. I didn’t know anything. I had no notification. They totally surprised me. Two prosecutors entered and said there was a warrant for my arrest. ‘Why am I being arrested?’ They wouldn’t explain. But they searched the entire house.”“I’m the president of the local coca growers union coordinating board. They took my seal and stamp. My kids had been working on school projects, analyzing seeds. They took their homework, too. They took a chain off a bike, and any wires they could find, and they brought me to Chimoré, where we were, eight of us, in jail together.”

“They brought us in an airplane to La Paz. They had a pile of rifles, pistols, and old weapons. And they brought all those arms into court to paint us as terrorists. I don’t own any guns, or anything like that. But they put out dynamite mines, too, for the judge. It seems to them that it is a crime to have a nail, or a wire. I think this can only be the intervention of the U.S. Embassy. We’re the leaders here. We don’t agree with their ‘alternative development’ programs.”

Leonardo Marca Photo: Al Giordano D.R. 2004 |

Leonardo mentions that he has to go to La Paz – eleven hours from his home by car, more by public transportation – on Monday to plead innocent to the terrorism charges against him. “They’re only hearing four cases on Monday, but all 27 of us are going. When you have nothing to fear, you have to present yourself voluntarily.”

LA PAZ, BOLIVIA; MONDAY, 9:30 A.M., FEBRUARY 2, 2004: On the fourth floor of the prosecutor’s office, the defendants sit on the carpet – there are no chairs or waiting room – and have spread coca leaf on kerchiefs. They are chewing the medicinal leaf that helps them (and this reporter, and his photographer, too) to cope with the dizzying altitude. The farmers of the Chapare live about 200 meters above sea level. Today, they have climbed to 4,200 meters, plus four stories, above the ocean that their landlocked country never touches.

Coca Growers Wait in Prosecutor’s Office in La Paz Photo: Narco News Agency D.R. 2004 |

Today, the “terrorists” – all 27 of them… the eight whose homes were raided, and 19 more who were formally charged… – have zero armed guards around them. A lone court officer, unarmed, stands by the door, barely paying attention. No photographs are allowed here, but the vigilance is so slack that Narco News takes photos anyway, without being reprimanded, probably without being noticed.

Albino Paniagua Photo: Narco News Agency D.R. 2004 |

Albino Paniagua had been one of the leaders who stood in the front passageway with Casimiro Huanca after the soldiers had chased the peaceful protesters into the shelter. “We were in the doorway,” he remembers. “The boss of the (military) operation asked us to evacuate the offices. We had prepared a protest for this day with products for which there is no market, no price. It’s a farce. The soldiers then shot a gas grenade at us. We headed behind the building.”“This is the door to the assembly hall,” says Albino Paniagua. “Luckily, it had been chained with a padlock, or we would have all ran in there and been trapped, probably massacred. When the four soldiers entered the hallway in front, we ran to the side. But then there were nine more soldiers charging along the side. I saw two soldiers trap Casimiro. He was being held. He was protesting, shouting, ‘Let me go!’ I can’t say which soldier shot him. They all had helmets on. They all looked alike. The soldiers grabbed me by the shirt. I passed by the side of Casimiro. I heard the shots and I heard him cry out, ‘ayyyyyy.’ When I heard the cry, I also saw a soldier shoot at Fructuoso Herbas, point blank, a shot that ‘burns the clothes’ is what we say here. Fructuoso cried out, ‘Where is my foot. I have no foot!’ His foot was there but it was totally destroyed.”

“The soldiers then took off,” explains Albino Paniagua (above). “I took my shirt off so they might not recognize me as easily and ran out front, shouting, ‘there are wounded!’ Casimiro was spilling a lot of blood. It looked like he’d been hit in the testicles. There was still this intense smell of the gas. This moment, it all happened so fast.”

Now, this familiar voice and face to Narco News readers, who saw his friend shot down in cold blood just fourteen months ago, who had walked me through the crime scene to relive that horrible day, and said what the U.S. Embassy then denied publicly but secretly admitted in a cable from Arce Street to the State Department in Washington: that Casimiro had been murdered by state security forces. The truth was uncovered, four months later, in April 2002, by a Freedom of Information Act request filed by journalist Jeremy Bigwood. Read the details, here. You can also read some equally compelling Defense Information Agency documents, obtained more recently by Bigwood, here.

Today, this man, Albino Paniagua, who denounced a crime, who stood tall and brave against a real act of terrorism – the assassination of an unarmed union leader – and who was later proved to have told the truth by the State and Defense Departments’ own documents, is here in the prosecutor’s office, facing the incredible charge that he – and not those who persecute him and killed his friend – is a “terrorist.” Our old friend speaks…

ALBINO PANIAGUA WAS WITH HIS KIDS ON DECEMBER 11th, at home. It was 11:30 in the morning, on a day of school vacation. “My children came to the fields with me to work.” The cops followed out there to arrest him, and took him to the same jail cell, in his town, where the seven others whose homes had been raided were already behind bars. He continues:

“They put us on the airplane together with lots of guns and dynamite that were not taken from any of us. They had 50 weapons there, mostly old ones that look like they don’t even work. Did they think the judge would believe that we would dare to make terrorism in the 21st century with junk arms like those? That’s why we think this is an invention by the U.S. Embassy,” said the man who, two years ago, disproved a previous Embassy charade and cover-up. “They accuse me of being a narco-guerrilla, at the very time when we were organizing a national conference for our political instrument, the MAS party.”“Back when they killed Casimiro, we in the coca growers federation were in a transition from being just a union to becoming a political organization. Today, we’re already more powerful. We’ve elected many members of Congress. What they fear is that we, the Quechuas, the Aymaras, will take power by electoral means. That’s what they want to stop with this case.”

JULIO SALAZAR, 38, RAISES HIS FIVE CHILDREN IN THE TOWN OF ISINOTA. His house wasn’t raided. He learned of the charges against him through the media. “They never let me know I was on the list of the accused. But we found out, so now we’re presenting ourselves, here, voluntarily. They’ve made false accusations against us because we’re with the coca growers’ movement, which is also anti-imperialist and anti-neoliberal,” Julio smiles: “This is our crime.”

“Our job is on the side of democracy, to take power by the electoral path and through a Constitutional Convention to change our laws. These charges are intended to silence us, to intimidate us. But they’re not going to be able to justify it. They have testimony against us from the ex-candidates of other political parties who lost the elections and aren’t happy about it, so those people are the witnesses who now say we’re terrorists. They’re just losing candidates, though. This is about politics.”

Leonida Zurita Vargas Photo: Narco News Agency D.R. 2004 |

“Has the New York Times come to interview you, their great opinion columnist and accused terrorist?” I ask. She just smiles and nods her head in the negative.

“I’ve lectured at Harvard University, spoken in New York and Washington,” she explains. “Now I’m here because I’m a terrorist without arms.

“I wasn’t at home when the raids happened in December. I was in Mexico, at conferences and meetings of social movements.” Indeed, Leonida is probably the most renowned woman leader of the Bolivian coca growers on earth. She gets invited to many international gatherings. That makes her, also, the only one of the defendants who had ever been in the same conference hall or room with the Colombian Pacho Cortes, with whom they’re all supposedly in conspiracy. She elaborates:

“They say I have relations with brother Francisco Cortés. I only know his name is Pacho because I watch TV. As a member of the Bartolinas, the National Federation of Women Peasant Farmers, I attend lots of meetings. In July of 2002, I met him at an event in Santa Cruz. I think it was about biogenetic seeds. They also say I was with his wife at another big conference, and that I had my picture taken with her. That’s possible. At those events, we always get our pictures taken together.”“Look at how justice works in this country. A member of Goni’s government, Yerko Kukok, his Chief of Staff, charged with stealing 13 million bolivianos (about two million dollars), was only placed under house arrest and the prosecutors don’t even search his house. But our homes are raided. For us, the poor, they send 18 prosecutors to raid our homes and find nothing.”

Tomás Inturías Photo: Narco News Agency D.R. 2004 |

“It was seven a.m. when 30 troops and two prosecutors apiece were sent after eight of us, in different towns, to raid our homes and arrest us. I was out collecting firewood. My wife and four kids were at home. The police grabbed me on the highway. It was only when I got to the jail in Chimoré that I realized they had raided my house, because I saw things from my house there.”“They took the notebooks from my daughters and nieces that they had prepared in their physics and chemistry classes. Maybe they thought they were instructions on making arms. I also had 500 dollars saved. They took that, but they never listed it as evidence. Now they’ve brought us to La Paz. I don’t have any family here in La Paz, nothing. We live like peasants here. The testimony against me that claims I’m terrorist comes from one person, an enemy of mine, with whom I had a land dispute. So now I’m on the list of the accused.”

Williams Condori Photo: Narco News Agency D.R. 2004 |

His story is fascinating: In 1985, when the price of the tungsten fell, he and the other mining families were obligated by the government to move to the Chapare. “We found it very agreeable there, because tuberculosis was our main problem as miners, and the humidity and heat of the Chapare helps clean the lungs. They gave us ten hectares per family where we grow a diversity of crops: rice, yucca, banana, and also the coca leaf.”

“Ever since 1985, I’ve accompanied Evo Morales in the movement. In 1988, when they passed Law # 1008, against coca, the eradication, imposed by the United States, began and we started to defend our lands,” says Williams, who, in 1999, was elected as city councilor in Villa Tunari. Later, he gave up his seat to the substitute councilor, to move to La Paz and take the job in the national senate.

“This is a very practical case,” Williams says, matter-of-factly. “We’ve said we’re going to make the government comply with the people’s wishes, and they want to stop us. It’s clear that there are international pressures on this case, from the Embassy, because it makes no sense at the national level. Why are they doing this? Because they want to provoke us into an uprising, in order to be able to create the conditions for them to wage a coup d’etat. But we’re not going to fall into their trap.” He shrugs his broad shoulders, commenting, “eh, they’ve put us in jail before.”

- The Fund for Authentic Journalism

For more Narco News, click here.