The Narco News Bulletin |

August 16, 2018 | Issue #32 |

narconews.com - Reporting on the Drug War and Democracy from Latin America |

|

EL ALTO, LA PAZ, BOLIVIA, MARCH 2, 2004: "I'm a human rights defender, not a terrorist, and now the neoliberal governments and that of the United States view me as some kind of trophy because they have nothing else to show for their false war on drug trafficking and terrorism," said Francisco Cortés, the Colombian citizen, better known as "Pacho," in an exclusive interview with Narco News.

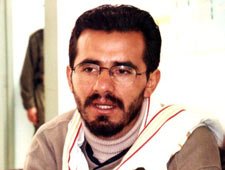

Francisco "Pacho" Cortés in the Chonchocoro prison Photo: Narco News Agency D.R. 2004 |

He is currently held in isolation with five other prisoners considered to be "highly dangerous," on the orders of the penitentiary directors: two of them are sentenced to 30 years in prison, the maximum penalty under Bolivian law.

"Why?"

It turns out that Pacho is a tíreless fighter, that he continues defending his rights and those of the other prisoners: he is the spokesman for the 23 prisoners detained here and is also the legal coordinator for the rest of the prison population.

What's more is that in the high spheres of the Bolivian government, they try to pin any activity that is considered "illegal" that happens inside this prison as the fault of the Colombian.

Prior to April 10, 2003, Pacho had never been imprisoned in any jail, not even in his homeland of Colombia, not in Bolivia, or in any other country. For the past 25 years his life has been dedicated to the defense of human rights, to social work, to protesting attacks against the most dispossessed, to constructing development projects, to renew human values, to stop the spread of transgenic seeds, and the strengthen agricultural organizations. He was also a schoolteacher.

On that fateful day, in a televised spectacle led by "anti-terrorist" police, Cortés was arrested, together with Claudio Ramírez, the former city counselor of La Asunta, and Carmelo Peñaranda, a leader from the Chapare, plus two minors of age who were released on personal recognizance.

The government of Gonzalo Sánchez de Lozada presented these "terrorists" first as members of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), but without any evidence. Later it accused them of being militants in the National Liberation Army (ELN), but had no proof of that either. In the end, they claimed that they were trying to form armed groups linked to drug trafficking.

Eleven months after his arrest, there are still no formal charges nor a shred of evidence.

The interview with this man accused of "terrorism" - the result of persistent overtures to the penitentiary director - was organized for 9:30 in the morning on Tuesday, March 2nd, in the Chonchocoro Penitentiary.

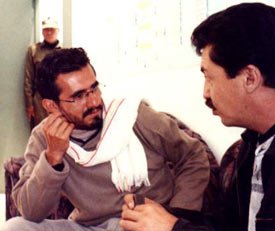

The author with Pacho Cortés, under the watchfull eye of the police Photo: Narco News Agency D.R. 2004 |

Although we had already received formal permission from the Prison Administration, the uniformed agents blocked my entrance into the prison "for being a journalist" and because all interviews at Chonchocoro must be authorized in writing.

Patience. Although in Bolivia it is still summer, the high plains wind is cold and the sun burns. We worked the cell phones to start again to be able to see Cortés.

At 10:45, the prison director, Colonel Ramiro Ulloa, arrived, and he asked us to wait a moment because he had to make some calls.

After a few minutes, two police officers signaled to us that we would be allowed to enter the penitentiary.

First, the officers inspected everything that we had brought. Although I was there to conduct an interview they prevented the entrance of a tape recorder and two cameras. They only allowed me to bring a notebook and a pen.

I explained the importance of a tape recorder or a camera in a journalistic investigation, but the police said that they had orders from superiors that no journalist could enter the jail with his work tools.

Oh well, the goal was to conduct the interview. There were many guards on the watchtowers and in the doors of the penitentiary, and two of them guided us to the place where we would conduct the interview.

At 11:05 a.m., Pacho entered the director's office of Chonchocoro, flanked by three police officers.

"Hola compañero, thanks for the visit," were his first words, followed with a hug to his sun and a firm handshake for the attorney.

Although I had never seen him before, only when he was presented as a "terrorist" in the Commercial Media, his slight build seemed thinner and his face burned by the high plains sun, with a new beard growing.

He mentioned that in eleven months of jail he had lost more than 25 pounds. "I'm thin as a rail," he said. He dressed in brown clothes, with a white windbreaker with lines of color and gray pants. He had a manila folder in his left hand with the colors of the Colombian flag: red, yellow, and blue, that he turned, every once and a while, as he answered questions: he appears to miss his land.

We began the interview and in spite of not having a camera nor a tape recorder, I did have a cell phone with a built-in digital camera to take his portrait.

Surprise! One photo, two... four, more... technology: It is said that these are the only photos of Cortés in Chonchocoro.

Pacho has not lost his accent when he speaks. He's fast, articulate, secure, and taking notes at this speed is work indeed: however, we kept up to par to not lose anything of what he said.

Meanwhile, the calls we made previously when initially we weren't allowed to enter already were having their effect. The prison director interrupted the interview to say that, yes, I can use the tape recorder and camera. We began the interview anew.

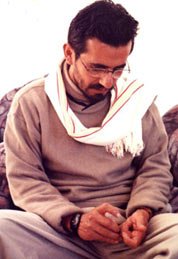

Cortés' health is not well. He suffers from an ulcer and a sharp gastritis, frequent nasal bleeding, hearing problems, kidney pains, light circulation and stress.

Pacho Cortés fears for his life Photo: Narco News Agency D.R. 2004 |

He confesses that although he had never been a consumer of coca leaf, he now likes to "pijchar" (the Bolivian word for chewing coca leaves).

He recognizes that being deprived of his freedom is affecting him psychologically.

"I have never been separated for so much time from my family. The most, I think, was for 15 days. I feel very worried and sad. Prison, in human terms, has too much affect," he says.

This Colombian citizen has always made his decisions collectively: "In my family we were never big money makers. We were serving the community," he stressed.

During the interview, we remembered the media show surrounding his arrest almost a year ago, and the words of the government oficial, José Luis Harb, who acknowledged the United States' participation in the "anti-terrorist" operation.

"There are treaties, conventions, and joint actions... in the fight against terrorism... Terrorist activity has an intercontinental character, and that's why we have agreements of understanding with any country, not just the United States," Harb said on that date.

In spite of feeling sick, Pacho takes strength and security in becoming more and more convinced that his case is more political than legal.

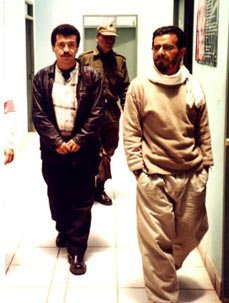

Cortés is transfered back to his cell Photo: Narco News Agency D.R. 2004 |

After more than an hour of the interview, which we'll continue, Monday, in Part VI of this series, Pacho told us that he does not favor the use of violence, although he remarked that violence is a consequence of the high levels of poverty and misery that exist among our peoples. "Violence exists everywhere, it is something natural," he says. "But terrorism is different because it causes terror in the population."

Remember that the events we lived through last October in Bolivia that led to 81 deaths and more than 500 wounded in the "gas war," and the fall of Gonzalo Sánchez de Lozada, can be considered as terrorism. Unfortunately, not a single authority has been punished. There is only impunity.

Paradoxically, this defender of human rights and life is submitted to an unjust imprisonment. His most elemental rights have been violated. "In Bolivia, it's not the crime that is punished, but, rather, being poor," Pacho affirms before holding out his hand to say goodbye...

Coming Monday: More from the Pacho Cortés Interview