The Narco News Bulletin |

August 16, 2018 | Issue #34 |

narconews.com - Reporting on the Drug War and Democracy from Latin America |

|

"How many peoples in the worlds that make up the world can say as we do, that they are doing what they want to? We think there are many, that the worlds of the world are filled with crazy and foolish people each planting their trees for each of their tomorrows, and that the day will come when this mountainside of the universe that some people call Planet Earth will be filled with trees of all colors, and there will be so many birds and comforts.... Yes, it is likely no one will remember the first ones, because all the yesterdays which vex us today will be no more than an old page in the old book of the old history."

- Subcomandante Insurgente Marcos, Our Word is Our Weapon, Seven Stories Press, 2000

Autonomy is our means and our end. It is both the act of planting our "tree of tomorrow," and that tomorrow of many different hues: rich, diverse, complex and colorful. Autonomy is freedom and connectedness, necessarily collective and powerfully intuitive, an irrepressible desire that stalls every attempt to crush the will to freedom. As the politics of escape attempts from capitalism in the North and the experience of liberated realities in the South, it is a global theme. The movements against capitalism have once again brought it to the fore - vibrant, alive, and urgently needed.

In the middle of the nineteenth century, a simple question was asked of a utopian community in England, and it is just as relevant today as it was then: "How do you get to a place where people live in harmony, and manage without money - by railway or rainbow?" By dreaming or doing? There are many answers and plenty of examples, some of which arise in this chapter, some of which are woven through the book, and some of which you have seen, thought of, imagined, or fantasized about.

We call these experiments in autonomy, though others might prefer freedom, liberation, or self-organization. The appeal of autonomy spans the entire political spectrum. Originally coming from the Greek and meaning "self" plus "law," it is at the core of the liberal democratic theory of justice and values such as freedom of speech and movement. Understood radically, however, it has been the terrain upon which revolutionary social movements have encountered each other throughout Europe; "autonomy at the base," from the grassroots, is the core organizational principle of the influential social movement known as Autonomia in Italy. Globally it has been a refrain of countless uprisings, struggles, rebellions, and resistance movements from the Zapatistas in Chiapas to the Organisasi Papua Merdeka (the Free Papua Movement) in West Papua, a colony of Indonesia. From the Cauca people of Colombia to the communities of Kerala in southwestern India and on to creating spaces for freedom the asamblistas and piqueteros of the Argentinean uprisings, people worldwide are developing political and social forms rooted in differing concepts of autonomy.

What is the appeal of autonomy today? We seem to have reached the point where trust in representative democracy has run out. The consistent betrayal by those who promise everything and deliver nothing has led many of us into apathy and cynicism. More profoundly some have begun to question the idea that our involvement in decision-making should be limited to a simple vote every few years. Participation, deliberation, consensus, and direct democracy are emerging from the margins and, in many instances, are being reaffirmed as the center of gravity for communities the world over.

Graffiti on the wall of a police station, Oaxaca, Mexico. Photo: CIPO/RFM archives |

- William H. Vanderbilt, 1879

"Break the rules. Stand apart. Keep your head. Go with your heart."

-TV commercial for Vanderbilt perfume, 1994

Our desire to influence the decisions that affect our everyday lives, however, has a powerful enemy disguised to seduce and lull into sleep that very desire. The culture of capitalism portrays autonomy as a key mechanism of the "free" market. For us to be free, the mythology goes, we must exercise our autonomy as consumers in the marketplace, where our bank balance determines our level of participation - in other words, we are free as consumers, where one dollar equals one vote.

By this same logic, the World Trade Organization, the International Monetary Fund, and the World Bank become advocates of "freedom." Freedom, that is, from "unnecessary regulation" and "barriers to trade" (such as environmental standards, trade union rights, corporate taxation, bans on child labor) - the freedom of money to flow around the globe at will. In such a "free" world, food, water, shelter, education, and healthcare are all trackable commodities. Insisting on them as basic rights rather than something to be bought, however, is a barrier to trade. But those basic rights provide the security that is at the root of a positive understanding of freedom as a freedom to do or to be.

For in order to be truly free - to create, co-operate, produce, dream, and to realize one's own autonomy through the respect and recognition of the autonomy of others - requires the freedom to be in the world and to have a network of care and support. The corruption of autonomy by "free" marketers is at the heart of the capitalist project - to capture the idea of freedom and sell it back to us. From "self" plus "law," they have fashioned the idea that individuals are actually a "law unto themselves." The market is presented as the logical development of our self-interest as well as the mechanism for its fulfillment.

We refute this notion of autonomy. It is not the tree of tomorrow that our movements are planting today. Our understanding of autonomy includes community owned and run healthcare, education, and social support; direct democracy in zones liberated by the people who live in them - not as enclaves or places to withdraw to - but as outward looking and connected communities of affinity, engaged in mutual co-operation, collective learning, and unmediated interaction. This is the reason for our impassioned defense of the mechanisms and support structures that have been fought for and won, the hard toil of movements who have struggled for hundreds of years - indigenous, revolutionary, and democratic.

Autonomy is always in process. But autonomy is often mistaken for individual independence which most of us understand as growing up, leaving home, finding work, earning money, making our own decisions: where to live, what to eat, what to wear, buy, and so on. But even where these decisions can be made (and in most of the world this fiction of independence is impossible), these choices are, in reality, entirely dependent upon the actions of others. That is, dependent upon the labor, transport, distribution, and exchange involved in the production of the food, clothes, house and so forth from which we gain our experience of "independence." Our lives are manufactured for us, instead of being the outcome of our choices and desires. Not only are we produced by this system, we in turn reproduce it by acting within its established parameters and boundaries and as long as we remain within these boundaries, we are perfectly "free" to go about life according to the paths offered to us by governments and corporations. In short, we are free to choose anything, as long as it doesn't defy the logic of capitalism. When we defy that logic, we soon discover the true limits of our "freedom."

The relationship between those with power and those under their command lies at the foundation of capitalism. Our capacity to create and to produce is separated from that which is produced - the "product," so instead of deciding together the best ways we can meet our own needs, while respecting the needs of others and the planet, our energies are appropriated to produce for the profit of others. Consequently, we are alienated from the very fruits of our work and work itself becomes something tedious, imposed, and suffered, rather than something imagined, anticipated, and creatively experienced. The creation of value and its concentration in things, or products, is then confirmed through their exchange in a market. This value invested in things means they quickly come to own us, rather than us owning them.

The relationship between those with power and those under their command lies at the foundation of capitalism. Our capacity to create and to produce is separated from that which is produced - the "product," so instead of deciding together the best ways we can meet our own needs, while respecting the needs of others and the planet, our energies are appropriated to produce for the profit of others. Consequently, we are alienated from the very fruits of our work and work itself becomes something tedious, imposed, and suffered, rather than something imagined, anticipated, and creatively experienced. The creation of value and its concentration in things, or products, is then confirmed through their exchange in a market. This value invested in things means they quickly come to own us, rather than us owning them.

Of course, most of us are not slaves. We can refuse, walk away, desert, quit, but where should we go and what should we do? This is the question and the challenge at the core of our consideration of autonomy. Refusal is only a real weapon if it is collective, with the combined creativity and strength that implies. Autonomy can never be about simple individualism, as we have been encouraged to believe. Autonomy is not about "consumer choice," whether wearing brands or boycotting them, choosing to drive an SUV or a biodiesel bus. No amount of "ethical consumerism," self-help, no amount of therapy, no retreat inside ourselves will allow us to make the jump. Autonomy is necessarily collective.

Homeless families living in squatted building, Porto Alegre, Brazil. Photo: Andrew Stern |

Of course, this is a simple way of describing a very complicated set of processes and the world is far too complex for easy explanations to hold up for very long. The means of producing, the nature of production, and what we might think of as products are all changing and have all changed. However, evidence that this powerful logic surrounds us and penetrates the everyday can be found in every sphere of life: from the marketization of basic needs such as water, to the patenting of gene types; from the opening of markets in healthcare, social services, and education, to the assertion of intellectual property rights; from the simulation of dissent to sell cultural experiences in everything from fashion to cinema and art, to the erosion of any distinction between the simulated and the real in popular culture - all are tainted by the logic of capital and the elevation of the commodity above all else. Under these circumstances it is no wonder that many of us respond with a sense of incredulity at the pace and complexity of life, a sense of helplessness, a feeling of being overwhelmed, and a general state of apathy in response to the willful appropriation of creativity and energy for which we are offered in exchange the most meaningless level of participation - produce, consume, die.

But once we act purposefully despite these constraints, we embark on a journey - a process of becoming which leads simultaneously towards freedom and connectedness, towards autonomy. We realize it through our connections to others, through interaction, negotiation, and communication. To be autonomous is not to be alone or to act in any way one chooses - a law unto oneself - but to act with regard for others, to feel responsibility for others. This is the crux of autonomy, an ethic of responsibility and reciprocity that comes through recognition that others both desire and are capable of autonomy too.

So when we talk about autonomy, we are not talking about or advocating a few journeys of independence; much less a withdrawal from the world into a kind of retreat. Something else entirely is happening, something rooted in this concept of autonomy as freedom and connectedness. A dynamic geometry of social struggle is emerging, fractal-like, where local autonomy is repeated and magnified within networks that overflow geographical, cultural, and political borders. On the horizon is an exodus - thousands of escape attempts, a mass breakout that is taking place globally. People are passing around the keys, exchanging tunneling techniques, tearing down the fences, climbing the walls...learning to fly.

What follows are a few of the branches of the complex tree of tomorrow that is autonomy. Through these stories, we hope to move beyond the idea that autonomy is "just" about deciding things with others of like mind in "ideal" communities that are often very different from those we usually experience in the everyday. Like stars on the horizon, some of these examples have burned themselves into our collective consciousness, while others are now faded distress signals echoing across other realities, re-visioned, transformed, and partially renewed in forms that may not even be recognizable to their founders and catalysts. None are perfect, and none are offered as "blueprints." All have in common an experimental quality, openness to possibility and contingency, and an intoxicating blend of creativity and courage which resonates across ideological barriers and national borders.

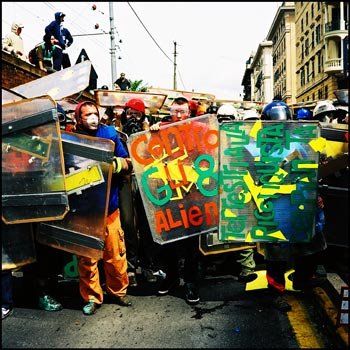

The Tute Bianchi use a unique blend of found objects to create body armor to protect themselves while they hold lines of defense against police attack. Genoa, Italy. Photo: Meyer/Tendance Floue |

- Sylvere Lotringer & Christian Marazzi, "The Return of Politics" in Italy: Autonomia, Post-Political Writings, Semiotext(e), 1980

"Autonomy at the base" was the core principle of Potere Operaio (Worker's Power) - the influential group and magazine that was at the heart of social unrest in Italy during the late 1960s and early 1970s, dissolving itself in 1973 to become part of a broader movement known as Autonomia (Autonomia Operaio). Autonomia as a movement never unified; as a series of fluid organizations and shifting alliances, it refused to separate economics from politics and politics from everyday existence. This approach led ultimately to the idea of refusing waged labor and to the extension of struggle from the factory (occupations, sabotage, and strikes were commonplace) to the city (20,000 buildings were squatted between 1969 and 1975) and on into the lives of what was termed the "socialized worker." The state finally crushed Autonomia as an active political force beginning with the April 7, 1979 arrests. Over 1,500 intellectuals and militants were imprisoned within a year.

But how does this relate to us today? In many ways, Italy remains something of a political and cultural experiment in the possibilities and potentials of autonomous forms and processes, currently embodied in the Disobbedienti (Disobedients), the network of social centers and autonomous groupings that has grown in the wake of the G8 protests in Genoa, 2001. The Disobbedienti emerge from the Tute Bianche, a movement tool and strategy of confrontation that became renowned during the Prague protests against the World Bank and IMF for wearing white coveralls and deploying body armor made of foam padding and bubble wrap to ward off police batons. Their white coveralls are an ironic celebration of the mayor of Milan's comments on the eviction of a social center in 1994, a popular community space in which cultural events, free meals, and political discussion brought workers, immigrants, students, and neighbors together. The mayor remarked, "From now on, squatters will be nothing more than ghosts wandering about in the city!"

These "white ghosts" sought a visibility from which to celebrate the margins, experiment with both local democracy and terrains on which diverse social groups can encounter each other. Tute Bianche's use of the body as barricade and bludgeon during actions epitomizes the need for presence, the desire to be an obstacle; it also dramatizes the futility of endless debate about violence and nonviolence. Putting bodies on the front line in this manner allows for confrontation while calling for restraint, for resistance to the temptation of resorting to further violence, engaging in a battle with the state on its own terms. It clearly opposes the needless descent into civil war:

"...we do not have to turn this space of revolt into a war zone. We have to think of the conflict in a different way. We call it 'disobedience,' conflict and consensus, an action always open to experimentation, open to transformation and rethinking the movement. We could have gone to Genoa carrying molotovs and we decided not to, because it does not work against the bullets and the Carabinieri's trucks that chase demonstrators. We also had to confront the police force. We built barricades after they shot at us. But we are always holding ourselves back in order not to be dragged into a civil war. That is what power wants: for the conflict to become a war."- Luca Caserini, spokesperson for the disobbedienti, interviewed by Ezequiel Marcos Siddig in Z Magazine

The deepest desire of the state in such circumstances is for an escalation through violence that leads to the prison cell and grave. The Italian legacy of armed struggle, which ended with hundreds in prison in the 1970s, was instrumental in teaching the Disobbedienti this lesson. Refusal to engage in a confrontation whose rules are established by the state is a pre-requisite of autonomous action; the stakes are incredibly high as the experience of a generation of Italian activists indicates.

The danger of celebrating confrontation whether (as the Seattle slogan suggested) "we are winning" or not, is that our aspirations and tactics are once more reduced to a simple binary opposition. In reality, who "we" are is never clear, what winning means is always difficult to ascertain, and those who would rather "we" didn't win often take a far longer or broader perspective. As the Disobbedienti argue, strategy is crucially important, as is communication, adaptability, knowledge, and willingness to listen and change. Where confrontation is necessary - and it is always likely to be necessary - an autonomous strategy requires us to be free both from the constraints of rules established by the powerful and from our own expectations that resistance requires us to always meet force with force. True autonomy means new and variable tactics, learning patience in order to flow around and above obstacles, learning to retreat, disperse, and then regroup to swarm and surround. It requires us to educate and communicate, and to be grounded in and to nurture support within constituencies beyond narrow communities of activism. All of this is essential to the practice of radical social change and all of it is essential to the idea of autonomy as freedom and connectedness.

Women in India, members of the 10 million-strong Karnataka State Farmers' Association, destroying Monsanto's genetically modified crops with the consent and participation of the farmer who was growing them. Photo: KRRS archive |

Some of the most interesting are coordinating through networks of communication and information exchange. Some are shaped by specific issues, or are clustered around social divisions such as race, class, gender, disability, sexuality, or age. Others are unique because of particular cultural traditions or sensibilities, or because of geographical location, or perhaps their courage in the face of overwhelming opposition. And for some autonomy is a whole way of being, living in communities that are liberated, directly democratic, and self-organizing, communities of struggle where the politics of autonomy have been realized in the social practices and day-to-day existence of alternative realities.

The Kuna people live on a series of 50 tiny islands in an archipelago of 360 known as Comarca Kuna Yala, situated in the Pacific Ocean and straddling the Colombia-Panama border. They gained autonomy after a bloody struggle with colonial police in 1925. Today 70,000 Kuna manage their day-to-day affairs through an elaborate system of direct democracy that federates 500 different autonomous communities within the Kuna General Congress, which meets once every six months. Each community and each inhabited island has their own internal rules and regulations, and is completely autonomous from the others; the only obligation is to send four delegates to the congress in order to enable coordination and to facilitate decisions on issues that relate to all Kuna. As Ibe, a Kuna activist points out in an interview: "If the government (ie: the Panamanian government) wants to carry out any kind of project within the region it has to consult the Congress. It has to be subordinate to the Congress, and the Congress has to make the decision - it has the last word."

Their autonomy is not a matter of mere theory, or of the formal but tokenistic recognition of indigenous rights. When the Panamanian government granted a Canadian mining company license to explore and exploit Kuna territory, that permission was revoked by the Kuna. Equally, the government was refused permission to install a naval base in Kuna territory. And the Kuna are neither localist or naive: they have independently negotiated rights to their territorial waters for the purposes of laying trans-Atlantic fiber optic cable for improved web links between South America and Europe. They are also active with local and regional groups within Peoples' Global Action in resistance against Plan Colombia - a joint project between the Colombian, US, and EU governments which has heavily militarized the region. As Ibe puts it: "Our organization wishes to struggle and to fight together, as fighting is necessary, without distinguishing between different ideologies, colors, or nationalities. The practical effects of globalization for PGA affect all oppressed people, and not only the Kuna or the indigenous people are oppressed: blacks, peasants, unions, and syndicates are also oppressed. But we should act with respect for diversity of culture, diversity of opinions, and the diversity of all the people who live on the planet."

Their autonomy is not a matter of mere theory, or of the formal but tokenistic recognition of indigenous rights. When the Panamanian government granted a Canadian mining company license to explore and exploit Kuna territory, that permission was revoked by the Kuna. Equally, the government was refused permission to install a naval base in Kuna territory. And the Kuna are neither localist or naive: they have independently negotiated rights to their territorial waters for the purposes of laying trans-Atlantic fiber optic cable for improved web links between South America and Europe. They are also active with local and regional groups within Peoples' Global Action in resistance against Plan Colombia - a joint project between the Colombian, US, and EU governments which has heavily militarized the region. As Ibe puts it: "Our organization wishes to struggle and to fight together, as fighting is necessary, without distinguishing between different ideologies, colors, or nationalities. The practical effects of globalization for PGA affect all oppressed people, and not only the Kuna or the indigenous people are oppressed: blacks, peasants, unions, and syndicates are also oppressed. But we should act with respect for diversity of culture, diversity of opinions, and the diversity of all the people who live on the planet."

Residents of land submerged by the Pak Mun River dam project live in houses built on stilts, refusing to leave their flooded land. Periodically they occupy the dam itself, demanding retribution and an end to further construction. Thailand. Photo: Velcrow Ripper |

Networks such as the Zapatista-inspired National Indigenous Congress show that far from a retreat to localism, the organizational dynamic of the EZLN has always been towards regional, national, and international collaboration. Autonomy as practiced by the Zapatistas is about inclusion and connection, about projects and actions that form a whole, over and above the capacity of any group or individual to determine or impose a particular direction or outcome.

Zapatismo is therefore the emergent philosophy of a constellation of essentially autonomous projects. From the indigenous women's initiative which specified a series of women's rights contrary to the patriarchal culture that surrounded them, to the autonomous Zapatista National Liberation Front (the unarmed civil society branch of the Zapatistas), to the national and international gatherings known as encuentros that subsequently led to the founding of Peoples' Global Action and had a significant influence on the development of the world and regional Social Forum movement.

All these examples of autonomy challenge the basic tenets of state power and the continuance of government in anything like its present form. In a similar way to the Kuna, the Zapatista revolution in thinking and practice did not taken place in a vacuum, but is rooted in an analysis of the national and international context within which they find themselves. Consequently, while negotiating for indigenous autonomy and civil rights during peace talks in San Andrés Sakamchíén, the Zapatistas were simultaneously pushing for profound constitutional reforms that would have in effect begun the process of dismantling the existent power structure of Mexican society. This was only realized by the government after their representatives and negotiators had reached the final stage of the peace accords - and it is a major reason why the Mexican government failed to implement those accords.

The Zapatistas also bypassed the state through the organization of a consulta: a program of popular education involving 5,000 Zapatistas traveling the length and breadth of Mexico followed by a plebiscite on the San Andrés peace agreement. As a result, over three million Mexicans voted for its ratification. "You came and found us sleeping, but now we are awake," said one old man from Morelos who took part. Participation, deliberation, transparency, and democracy are at the forefront, essential to the transformative power of autonomy.

Examples such as these are found globally, and everywhere the refrain is the same. In Indonesia, a system of regional autonomy introduced in 1999 as a means of responding to global market pressures for productive flexibility has instead led to incredible innovation amongst civil society, as well as a qualitatively different way of doing politics in some areas. In the Mentawai Islands, the ideal of replacing government with a lagai, a consultative and deliberative body is gaining momentum as, they suggest: "the functioning of mainstream politics contradicts the ideals of dialogue in pursuit of a generally acceptable lagai-based consensus."

In the village of Mendha in the Gadchiroli district of Maharashtra State, in India the slogan is "Mawa mate, mawa Raj," (in our village we are the government). This autonomy began with their opposition to the incursions into their forests by Ballarpur Paper Mills, which they subsequently defeated. In defiance of central government, they developed a system of forest and watershed management, as well as new methods of honey production realized through their system of participatory democracy and self-organization. Up to 1,500 such villages across rural India have been recorded taking similar steps. In these villages, government officials fear to tread.

The everyday reality of autonomy then, is one which is rich, diverse, and complex and once embedded, is difficult to root out, for like Mendha's honey, the taste of freedom and the inspiration of connectedness are unforgettably sweet. In many communities of struggle, autonomy is the beating heart of defiance, simultaneously echoing the rhythms of the everyday, which are also the rhythms of resistance.

A young piquetero participates in a city-wide road blockade, which seals off the capital. The piqueteros are a movement of poor and unemployed workers, whose blockades put pressure on the government to meet their demands for jobs, food, and social welfare. Buenos Aires, Argentina. Photo: Andrew Stern |

It is educating your child, occupying a building, refusing a job, working for satisfaction rather than money, and achieving everything. These escape attempts, though small and often unseen, coalesce in cycles, and sometimes they grow and spread exponentially. Previously they were easily co-opted, their threat neutralized, because they were isolated attempts - from brief transgressions to large mobilizations, they often signified singularity rather than solidarity.

In contrast, the movement of movements against capitalism is composed of groups, (dis)organizations, networks, and constellations of networks that are linked to each other through struggle. There is nothing new in this except that most of those active within these movements are now vibrantly aware of these links - the strategies, forms of action, modes of decision-making, and of course, the common enemies. Previously, episodes of resistance such as the rise of Zapatismo would have been a footnote in the history of indigenous rebellions, a brief flare on the horizon; now they are the digital archive of a global revolutionary consciousness, a whole vista set alight. These links are fostered by communication technologies, travel, and gatherings where people can meet, interact, learn, teach, and struggle together. These spaces have been and continue to be crucial to the vitality and the continued expansion of this global cycle of resistance.

In contrast, the movement of movements against capitalism is composed of groups, (dis)organizations, networks, and constellations of networks that are linked to each other through struggle. There is nothing new in this except that most of those active within these movements are now vibrantly aware of these links - the strategies, forms of action, modes of decision-making, and of course, the common enemies. Previously, episodes of resistance such as the rise of Zapatismo would have been a footnote in the history of indigenous rebellions, a brief flare on the horizon; now they are the digital archive of a global revolutionary consciousness, a whole vista set alight. These links are fostered by communication technologies, travel, and gatherings where people can meet, interact, learn, teach, and struggle together. These spaces have been and continue to be crucial to the vitality and the continued expansion of this global cycle of resistance.

Keeping these spaces open is essential, as is retaining a balance between the need and desire of groups to operate independently - autonomously. We also need a level of coordination to increase communication flows between ourselves, and to ensure that participation at regional and global levels is participatory and democratic. Network forms of organization, such as Peoples' Global Action have been crucial to the development of global resistance and the coordination of autonomous projects within a broader framework which itself seeks to be autonomous.

Other spaces of coordination reflect the emphasis on popular processes of deliberation, discussion, and education that are such a feature of the liberated zones of the Kuna, the Zapatistas, and others. In 2000 in Spain, for example, activists facilitated a social consulta on the question of abolishing external debt. Over 10,000 people got involved in 500 neighborhood assemblies, and ultimately over one million people voted by 97.5 percent to abolish the external debt. This process was subsequently made unlawful by the state judicial authorities. Fourteen countries across Latin America have conducted social consultas on the Free Trade Area of the Americas - in Brazil ten million voted against it in a civil society referendum in September 2002. A European social consulta, is now being organized, seeking popular involvement catalyzed by autonomous promoter groups working in their own localities.

In Los Angeles, the Bus Riders' Union is a trilingual organization composed of the urban poor who are dependent upon public transport for work, education, and leisure. Militant and carnivalesque strategies of confrontation, including non-payment of fares, theater skits, and onboard teach-ins through bus-based educators and organizers has forced the Metropolitan Transit Authority and the courts to recognize them as the voice of an incredibly diverse coalition. Race, class, gender, disability, and the environment have been highlighted in a vibrant and massively effective campaign that has helped keep fares low, led to the replacement of older diesel buses with newer compressed gas models, and ultimately increased passenger numbers as confidence grows amongst the black and ethnic minority, female, and poor communities that are so in need of decent public transport. Organized independently of political parties and operating with a high degree of autonomy and internal democracy, this organization has resonated with others across North America, and new Bus Riders' Unions have sprung up in many large cities.

In Los Angeles, the Bus Riders' Union is a trilingual organization composed of the urban poor who are dependent upon public transport for work, education, and leisure. Militant and carnivalesque strategies of confrontation, including non-payment of fares, theater skits, and onboard teach-ins through bus-based educators and organizers has forced the Metropolitan Transit Authority and the courts to recognize them as the voice of an incredibly diverse coalition. Race, class, gender, disability, and the environment have been highlighted in a vibrant and massively effective campaign that has helped keep fares low, led to the replacement of older diesel buses with newer compressed gas models, and ultimately increased passenger numbers as confidence grows amongst the black and ethnic minority, female, and poor communities that are so in need of decent public transport. Organized independently of political parties and operating with a high degree of autonomy and internal democracy, this organization has resonated with others across North America, and new Bus Riders' Unions have sprung up in many large cities.

In Canada, the Ontario Coalition Against Poverty (OCAP) is another example of autonomous organizing based upon alliances forged across social divisions. OCAP was founded in 1990 and intervenes using instrumental direct action aimed at obstructing the application of neoliberal policies employed by the state or national government. This involves "direct action case-work," focusing on issues and events which are directly relevant to the quality of everyday life experienced by oppressed communities. The casework involves a process that requires active resistance at the point where it can make a difference - not symbolic protest, or advocacy, but building communities of struggle and respecting the autonomy of those communities to self organize.

OCAP has had success working against homelessness, poverty, police harassment, privatization, deportations, and corporate power. As an avowedly anticapitalist organization not allied to any political party, they have attracted members from different ethnic and class backgrounds, and have shown clearly that to organize in a way which can make a difference often means being prepared to fight. As OCAP organizer Jeff Shantz says, "as long as movements remain trapped in methods of limited protest, governments and profit-seeking regimes will continue to escalate their attacks on poor people, people of color, and the Earth."

It is easy to call for a fight and easier still to lose one, but it is very difficult to sustain a serious defense against the ever-more regressive and brutal tactics of the state. However, OCAP's autonomy and vitality has enabled them to mount such opposition. For their strength lies in the roots of their organization - rather than being content to mirror the liberal call to "tolerate diversity," they practice an actual unity in diversity, and this means they draw upon a wider constituency than many similar activist organizations.

As Thomas Walkom wrote in the Toronto Star, OCAP is: "An eclectic band that includes not only poor people, but students, retirees, and the odd university professor, OCAP doesn't play by the usual rules. It is direct, in your face, and occasionally rude. Where other protest groups try to make their points by holding demonstrations in authorized public spaces such as Nathan Phillips Square, OCAP tends to take the fight right to where its enemies live."

In OCAP, we have an example of how "new" strategies of direct action have reinvigorated campaigns around perennial social realities of poverty and inequality. Similarly, in the new networked spaces of PGA and the myriad processes of consultation, we have a model for how everyday social realities might come to inform each other while retaining the autonomy each prizes so highly.

Brazil's landless peasants celebrate occupying new land, Brazil. Photo: Sebastião Salgado |

The politics of autonomy encourage us to push for and take, to refuse, to be prepared to fight, and to escape, exit. For to exit is also to take, to take ourselves out of the context within which we are ensnared, to choose differently, to re-invent our circumstances, and to decide what it is we should, or need, to do. Autonomy is a key demand of a complex movement, a tree of tomorrow whose deep roots were planted in yesterday and today, and are spreading everywhere.

This essay opens the chapter "Autonomy" in the book We Are Everywhere. Other stories in this chapter include:

For more information about the book We Are Everywhere, see the book's website. For a special offer to purchase a copy of the book, the Authentic J-Store is now open at Salón Chingón.

Essays from We Are Everywhere on Narco News:

Narco News Publishes Seven Essays from We Are EverywhereEmergence: An Irresistible Global Uprising

Networks: The Ecology of the Movements

Autonomy: Creating Spaces for Freedom

Carnival: Resistance Is the Secret of Joy

Clandestinity: Resisting State Repression