The Narco News Bulletin |

August 15, 2018 | Issue #44 |

narconews.com - Reporting on the Drug War and Democracy from Latin America |

|

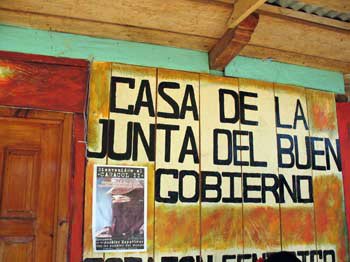

In his December 24 communiqué, Comandante Moises of the Zapatista National Liberation Army (EZLN in its Spanish acronym) invited the people of the world to the first "Encuentro de los Pueblos Zapatistas con los Pueblos del Mundo" (Meeting of the Zapatista Peoples with the Peoples of the World). He said: "We are only trying to show what we are building, with many difficulties, but also with many desires constructing another world, one in which those that command, command obeying."

Foto: D.R. 2007 Gerardo Osuna |

Health care in the indigenous communities of Chiapas has long been neglected by the Mexican government.. A shortage of medical supplies and transportation, the loss of traditional medical knowledge, barriers to sexual education and the hazards of dependence on foreign aid were some of the issues raised by the five participating councils of Good Government ("Juntas de Buen Gobierno") and visiting delegates at the December 31 session on health. The Zapatista communities have thus organized their own health care network, and called in help and resources from other organizations in solidarity throughout Mexico and the world.

Celia, a coordinator of health from the northern zone of Oventic, noted how resources from abroad have boosted autonomous health projects. Built in 1991 by local Zapatista communities with aid from foreign donors, the hospital of Guadalupe in Oventic is the pride of the local communities. Functioning without any government support, this hospital provides service to those suffering discrimination in state-run institutions. Karina, a member of the Junta de Buen Gobierno and representative in the area of health from the Caracol 1 at La Realidad, also acknowledged international investment in the health system.

Foto: D.R. 2007 Gerardo Osuna |

For example, during a recent visit by your correspondent to a Zapatista community in the canyons region, a local health promoter warned against developing a dependence on foreign assistance. Speaking with The Other Journalism, the health care promoter noted that modern facilities require continual investment in order to operate. The issue goes beyond one-time infusions of funds. This is the case with one small clinic in the Cañadas de Ocosingo. A plaque commemorating aid donors hangs on a wall of the one room clinic with fading paint; the pharmacy sits empty. This community, along with others in this canyon, cannot fully exploit such clinics without electricity to run refrigeration for volatile vaccinations. This is a problem that foreign aid organizations by themselves cannot solve.

The three ambulances sitting next to the Guadalupe clinic are a reminder of the disparity within Zapatista communities. Though the ambulances line up at Oventic, often they are unable to reach outlying areas. This problem was graphically illustrated during my stay at the above mentioned community. Late at night a woman seven-months pregnant arrived at the community to await transportation to the autonomous hospital at the Caracol of La Garucha to receive medical attention related to abdominal pains she was experiencing. However, the soul ambulance for the four municipalities situated 5 hours away at La Garucha never arrived. In this case, it was finally the healing knowledge of the local promoter of health, employing a natural painkiller that allowed the patient to return home the next day. Karina reminds the audience of the critical lack of medical transportation in many of the municipalities. "We had to carry our sick for days, they could not receive medical attention. This is why many of our grandparents died, trying to reach a doctor in the cities far from our communities. This experience taught us to teach ourselves and to organize for ourselves."

Foto: D.R. 2007 Gerardo Osuna |

In a moment of solidarity with indigenous peoples of Chiapas, Kamahus, a speaker from the First Nations of Canada, recounted her own story of struggling to maintain traditional methods of healing and specifically her experience with ancient practices of childbirth. In her words, "the genocide of the conquest of America of the north tells a similar story of the loss of our grandmother's knowledge in the area of midwifery. Generations of the absences of traditional midwives left her alone without someone who could accompany her as she delivered her own children by a clean stream in the mountains." The story she told resonated with the experience of the indigenous women of Chiapas.

Representatives from the five Zapatista regions noted the importance of maintaining a continuing and open discourse on complex and sensitive subjects of sexual health. Health education, particularly sexual health, was a topic of particular interest among many of the national and international participants present. The discussions that took place, between Ingenious and non-indigenous participants, demonstrate that ideas (and not just funding and technology) flow in and out of Zapatista territory, and have influence on such issues as sexual education and women's rights to control their own bodies.

Foto: D.R. 2007 Gerardo Osuna |

From inside his cell at the penal de Santiaguito, Dr. Guillermo Selvas Pineda, arrested last May in the central Mexican town of Atenco as he sought an ambulance for wounded student Alexis Benhumea (1984-2006), sent a hand-written message of goodwill to the growing interest in health. As one of the first doctors to work with the insurgents in the mountains, he knows the suffering that has been experienced by Zapatista communities. He invited other doctors to join the growing number of people from outside and inside the region who are working to build an autonomous health service, one of the key political goals of the Zapatistas movement.