The Narco News Bulletin |

August 16, 2018 | Issue #32 |

narconews.com - Reporting on the Drug War and Democracy from Latin America |

|

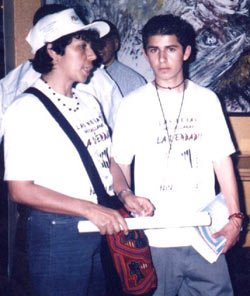

Lilia Vargas, with her son Andrés Cortes Photo: Alex Contreras Baspineiro D.R. 2004 |

Lilia is a brown skinned woman, thin but with strong arms, and firm in her responses. Although she conveys sadness through her memories, she also expresses hope that her detained husband will regain one of the rights that we human beings most anxiously desire: freedom.

Pacho's wife is also alleged to be one of the leaders of the National Liberation Army (ELN, in its Spanish initials) and a fugitive from justice, but she offers a smile in response to these charges. And, she has good reason to laugh: Where else does a fugitive from justice meet with important Colombian government officials, ambassadors and prosecutors? Where else is she respected in the offices of the Interior Minister, the Public Defender, and the Vice President of the Republic? These are all places where her husband also has earned a lot of respect.

On Monday, February 26th, at three p.m., this correspondent arrived at an office located in downtown Bogotá that serves as the headquarters of the Social Corporation for Community Training and Auditing (COSPAC, in its Spanish initials). COSPAC is a non-governmental organization, led by Francisco, whose work is based on advising and working with peasant farmer communities on various projects.

As this peasant farmer leader and worker - who promotes a focus on women in different rural communities - holds out her hand, we understand that, in Pacho's absence, she has the reins of COSPAC.

Lilia knows that she doesn't have to hide and that she's not any kind of fugitive from justice, as - in the scant coverage his case received in the Colombian commercial press - was claimed on the day after her husband's arrest last April in Bolivia by media such as the RCN news agency.

On April 10th, 2003, Colombian peasant farmer leader and human rights defender Pacho Cortéz was captured in La Paz, Bolivia. He was at the time a guest in the house of his friend, coca growers' leader Claudio Ramírez.

During the arrest - named operation "Early Alert" - Claudio, coca grower Carmelo Peñaranda and Nelly Ramírez (Claudio's daughter) and Betty Nina (his niece, both minors) were also at home. All of them were handcuffed and brought in under intolerable conditions, under the pretext that they were all accused of "terrorism," and "narco-trafficking," and of "belonging to armed organizations," among other charges.

In the spectacular operation, various Commercial Media correspondents were also called to witness the raid, curiously, by the U.S. Embassy in Bolivia.

Some absurd charges remain against Pacho: that he is at the head of the ELN in Colombia, the strategist or a plan to form an armed group in Bolivia, and, for good measure, involved in espionage and narco-trafficking.

To shed light on the matter, Lila speaks to Narco News about who Pacho is; her viewpoint as wife, mother, woman, and companion in the arduous struggle to defend the human rights of the Colombian peasant farmer: We also speak of the judicial process, the campaign to free Pacho that is underway on the national and international levels, the role of his attorneys and about the difficult situation that the Cortés family must deal with regarding their safety in Colombia, among other issues.

Narco News: Let's begin at the moment that you met Pacho. How did that happen?

Lilia Vargas: Well, in the first place I want to say that Pacho and I have been married for 23 years. We are both of peasant farmer roots, from the town of Bolívar in the state of Santander. We've known each other since we were children in the same neighborhood. There, my father and Pacho's father were always the leaders. So we both came from the same school.

Like me, Pacho was the oldest of a family of 12 children. When he was 12 years old he was already the president of the Community Action Board. He came from a very Catholic family. In fact, his parents wanted him to become a priest. From there he finished primary school in the neighborhood and they sent him to study for his bachelor's degree in Zapatoca, Santander, in a school for future priests, with a scholarship from a senator of that state, owed to the fact that he was recognized as a person who was very active in his community.

There, he joined the seminary, and worked in the field conducting catechisms. After that he couldn't continue studying, because his family was very poor. He could only complete his bachelor's degree. But then they gave him the chance to work as a teacher in a school. However, he continued with his work as a seminarian. He was a counselor. He always had that charisma for winning over people. He was professor Pacho, and I was his student. From there we began to date each other, and ended up as a couple...

Narco News: How were your first years together?

Lilia Vargas: After being in Santander, he ended up with a contract from the Education Ministry and then we went to Cúcuta (North of Santander)... We worked there for a while, but there wasn't much of a budget. There we had to do whatever was necessary to make ends meet, including working as salespeople.

One year later, in 1983, we went to the state of Arauca (the Southwest of Colombia), and we were in the farm country... A brother of his had lived there a good while already. He brought Pacho to a meeting of the Community Action Board of that area and introduced him to various people. It was difficult for a teacher to work in that rural area because there were no roads, one had to get there on foot, on horseback, or via the river. In that meeting, Pacho spoke about what he had done in Santander, his trajectory as a teacher, and how he liked community work a lot. The Community Action Board immediately petitioned a local school in Arauquita to hire him to work there.

He went to the Villanueva school as a teacher and continued working there for seven years. He brought the people together to pray the rosary every night in the school and as he had always liked to work in the farm country, he began to work in the National Association of Peasant Farmers - Unity and Reconstruction (ANUR-UR, in its Spanish initials).

Narco News: How is the work of the association connected to the peasant farmer movement?

Lilia Vargas: Working with the association really attracted him, because he likes social work. The countryside in Arauca doesn't have broadcast media, or good roads, or hospitals, or schools. And he thought that he could change that through the association.

After Pacho became connected to ANUC, he was involved in many national and international activities. For example, in 2000 there was an event in Costa Rica to open up a new negotiating space between the FARC, the ELN, and the government, with different social organizations acting as intermediaries. Pacho was one of the people who called and organized that meeting.

In the year 2000, after all the work we had done in Arauca, we left ANUC and started this NGO (COSPAC), where the people of the region named Pacho as director and legal representative.

At that moment, Pacho, already being the director of the institution, he made his first trip to Bolivia, to Cochabamba, where there was a meeting of international organizations titled "Peoples Global Action." They invited him there as the delegate of the peasant farmer sector in Colombia. Later he made a second trip, in 2002, to organize an interchange by peasant farmer and indigenous organizations in Bolivia, since this country had always been, for us, an example of good popular organization.

Narco News: As a peasant farmer leader and human rights defender, what has been Pacho's position on issues like narco-trafficking?

Lilia Vargas: In the Eastern Central region of the country three organizations were formed which Pacho headed, expressing his worry about the planting of crops for illegal use. At the same time he has denounced the consequences of the fumigations. In one mission he made to the Putumayo to verity the problems of illicit crops, fumigations, and human rights, Pacho attended as a delegate, together with the Colombian coca growers' leader Eder Sánchez and Bolivia's Evo Morales.

Narco News: When did the threats and persecutions against your husband begin?

Lilia Vargas: Ever since they elected him as president of the ANUC in Arauca. His work became very complicated, because he was denouncing human rights violations by those who were running the state.

1989 brought the worst persecution against us there. On August 12th of that year we had to come to Bogotá because the Army bombed the plantation where we lived. That was the first time we were displaced.

In May of 1999, we asked the Interior Minister that we and other social leaders be given protection. This office made a risk assessment study and accepted our petition. From there they gave us cell phones to help with our safety, as in that era the threats were coming via email to ANUC, signed by the Central Bloc of the AUC paramilitaries, against different members of the organization who were working here in Bogotá.

After Pacho had denounced the massacre on a bus in the Yopal-Sogamoso route (in Casanare, in Northeastern Colombia), and had participated in a march to protest that attack, we received constant threatening calls for two weeks, when our children were alone, asking for Pacho and for me, saying that they needed us to attend meetings that, in reality, didn't exist. The truth is that it seemed like they had both of us under surveillance and were unable to find us because we were both in the field working.

But the worst of the persecution was the attack against our children. The had bothered us so much that we had to move many times, and change our kids from school to school.

Narco News: What were the final activities that Pacho realized as a leader before he traveled to Bolivia?

Lilia Vargas: Five days before Pacho traveled to Bolivia, he denounced what had occured in October of 2002, in Recetor, a province of the state of Casanare. There, from October to January, about 50 people had been disappeared. What's more is that Pacho had practically organized a verification mission about what had happened there, but until now nobody has taken charge of the case.

Narco News: And now, after his arrest, how is the situation with your family's safety?

Lilia Vargas: The truth is that after Pacho's arrest, it's been a very complicated situation for us. One time they called me at home at 11 p.m. and said, "You old bitch, if you keep defending this son of a bitch, you're going to die." And I told them, "Well, then, I'll have to die, but I am going to show that Francisco Cortés is innocent."

In spite of the fact that we had changed the childrens' schools they continued following us. One day Andrecito, our son, then 17, had to go to Soacha (a neighborhood of Bogotá) to pick up his identification and they followed him from the apartment to there. As it went, the boy had to go to the police station. In that moment I thought it would be better to send him to Bolivia. Supposedly the government there has to guarantee his security and, at least, he can be following up on the case of his father.

The same thing happened with Cindy, my oldest daughter. Last May, when she came from Bolivia, after visiting her father there, one day my computer didn't work to check my email, and I sent her to a cyber-café to download my mail. There, some people knocked her to the floor and threatened her.

The last thing they did was last Thursday, when they called my sister's cell phone and told her: "If you continue seeing Lilia Vargas, you will die."

I filed a complaint with all the facts to the prosecutor, because I will not stay quiet with Pacho detained. I have protested his case nationally and internationally and I will continue doing it until we succeed in the goal of freeing him.

Narco News: What role are the governmental and non-governmental organizations, nationally and internationally, playing in the case of your husband?

Lilia Vargas: We filed the case before the Inter-American Human Rights Commission. They responded in December, accepting the case and beginning the process. Amnesty International has made various pronouncements. One delegation from the European Parliament sent a communiqué signed by 32 parliamentarians, among them Paul Emile-Dupret, who has known Pacho for a long time.

On October 8th I was at a meeting in Venezuela and was able to speak with Chávez. From that meeting, there came a declaration in which he called on the Bolivian government for the immediate release of Pacho, since they still have not proved a single accusation against him in that country.

And at the Ibero-American Summit of Presidents in Santa Cruz las October, he spoke out about the case. Also, we are approaching Lula through the Landless Peasant's Movement, Sin Tierra, to send a Brazilian attorney to Bolivia to help in the defense of Pacho and solicit political exile in Brazil for Pacho and his family.

On another hand, the first time the Bolivian prosecutors, René Arzabe and Silvia Blacutt, the ones who accused Pacho, came to Colombia to find evidence, we asked the Colombian foreign minister (Carolina Barco) if she would permit us to speak with them.

It seemed advisable to us, for the judicial process, that the prosecutors not only take what Military Intelligence says into account, but that they also listen to those who know Pacho's work. That includes the Vice President of the Republic, the Interior Minister, the Public Defender, and Colombian farmer and human rights organizations. The former Public Defender of Boyacá is ready to make a declaration in defense of Pacho. But the prosecutors refused to meet with us.

Also, the Bolivian ambassador in Colombia, Victor Belmonte, has received various petitions from us: One asked him to take Pacho out of solitary confinement, where they had put him in the beginning. The second was to transfer him to a different prison and the third was to guarantee that his family members could visit him.

The ambassador then called us to a meeting where he told us that the change in prisons was being processed, but that he couldn't guarantee that I could travel safely to Bolivia because that was in the jurisdiction of the judicial branch and not the executive. He also said that he wouldn't advise me to go because I would be arrested as soon as I got there.

Narco News: How do you see Pacho's legal situation at this moment?

Lilia Vargas: The Bolivian prosecutors made their second trip to Colombia looking for evidence. When they returned they didn't have any other choice but to admit to the Bolivian authorities that neither Pacho nor I have any charges against us for any crime in Colombia. And why is that? Because we asked the Colombian Attorney General to ask for Pacho's transfer from Bolivia to Colombia, arguing that if they were accusing him of being a member of the Colombian ELN, well, this is where it ought to be judged. The Colombian prosecutor replied that he couldn't do that because there are no charges in Colombia against Pacho.

In spite of it all, five months after his arrest, the Colombian Attorney-General spoke with Pacho and told him that the Bolivian authorities admit that they made a mistake: that he was not the person they were looking for, but he had to accept the charges because the prestige of the country of Bolivia was now on the line. He ended up telling him to take consolation in the fact that he would win his freedom within five years and he has to understand that the government of Bolivia is not going to publicly admit that it was wrong.

In addition to all of this, they already sent two guys to the prison to kill Pacho and they threatened him. That was when we asked the Inter-American Human Rights Commission to apply protective measures. The Bolivian justice system must be held responsible for anything that could happen.

Narco News: In recent days there was a report that your husband has been accused, without evidence, of having planned an escape from the Chonchocoro Prison. What can you tell us about that?

Lilia Vargas: This morning I listented to an interview with the prison's director and the chaplain of the parish of Chonchocoro, and they were asked what happened with the accusation of a massive escape. The priest responded that this is an example of the persecution that there is against Francisco Cortés, and that he was sure that he had nothing to do with any of it.

Yesterday they went and took him out of his cell. Now they have him isolated with six other prisoners. Any little thing that happens in that prison, the Bolivian authorities say, is Pacho's fault. In the end they do all this to be able to say to the European Parliament, "Look what this guy that you just defended is doing." It's their way of continuing to justify his detention.

The defense of Pacho, more than being legal, is political. We keep saying: Pacho is an innocent prisoner. It's very clear that the Bolivian government has him, at this moment, as a scapegoat to justify connecting the Movement Toward Socialism (MAS) party with Colombian rebels. But we are going to demonstrate that they are wrong and they will have to accept that they are committing the worst of errors since his capture.

Narco News: After visiting Pacho in prison, how do his children see him?

Lilia Vargas: He's in bad shape. It's very complicated for a person as active as Pacho, who likes to spend almost all his time in the countryside sharing with the people, is surrounded by four walls: for us, the peasant farmers, its serious when they take away our contact with the farm, with nature, because that is our life.

But we are still a very united family today and all our lives. Pacho and I have been together for 23 years. We both work in the same field and we have never before been separated for more than three months by any mission or international tour... that has been very hard, for him, and for us.

The most ironic thing of all is that those who first pushed the detention of Pacho now find themselves at the hands of Bolivian justice, too. For example, the minister Yerko Kukoc, who - before the prosecutors said they would accuse Pacho - went to the press, and to the world, and said that Pacho was a terrorist. And where is Kukoc today? He's facing corruption charges. Or, who was President Gonzálo Sánchez de Lozada? I don't think he left the Bolivian government because he was a good person.

All the people who set Pacho up are connected with the United States and want to show evidence of terrorists and narco-traffickers where they don't exist.

This correspondent left Lilia's office with the satisfaction of getting to know a woman who through her eyes shows that warriors still exist - but also with a sense of what could be sadness, rage, or impotence in the face of the fact that there could be a plot as absurd as this one that could be unraveled by a four year old child, but which is protected by the power of the world's largest superpower.

It is a superpower supported by ultra-fascist Colombian officials who declare war against the human rights offices, who designed the "Anti-Terrorist Law," and who themselves violate those same laws through their military and police. They try to forgive and forget the terrorizing crimes committed by paramilitaries. These paramilitaries are the same people that certain multinational and US soft-drink businesses and foreign oil companies hire, clandestinely, to exterminate hundreds of union leaders and workers.

Beyond thinking about the arrest of Pacho as a set-up by Bolivian authorities that want to dismantle popular social organizations that support coca-grower Evo Morales Alma's Movement Towards Socialism (MAS) party, we have to ask the question: Why hasn't the Colombian government protested this arrest as it should? Taking into account the serious accusations that Pacho has brought against them throughout his career as peasant farmer leader and human rights defender, do Colombian officials think this is the best way to take him out of the game without dirtying their own hands, in order to remove him as an obstacle to their intentions to grant amnesty to paramilitary groups?

In that sense, does Pacho's work constitute a danger to the powerful economic interests of the plantation owners, the ranchers, the investors, and, lastly, those who exploit the hardwoods and every day loot the natural resources of this country while selling their artificial products at low prices?

It is imposible to stop thinking about Pacho, isolated from the world, now accused of another crime he did not commit: attempt to escape. All of this demonstrates that in spite of the campaigns to free him, of the efforts by the attorneys and the pronouncements of the international community, the Colombian and Bolivian governments are unwilling to challenge what, after a simple look, is a case that has nothing to do with what they say it does. Instead, this is a case based on artifice and farce... manufactured by the United States government... and we'll have to wait and see when Pacho will be set free.

All that is left is to wait... but for how long?

Next in the Series: Last Tuesday, Narco News South American Bureau Chief Alex Contreras succeeded in being able to visit, interview, and photograph, Pacho Cortés in the Chochoncoro prison. Stay tuned for Pacho in his own words...